The Texas Abortion Case, Explained

How a Texas law could undo 43 years of access to legal abortion in the United States.

Updated February 3, 2016:

This story has been updated to reflect the new name of the HB2 case: Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt.

Original Story:

Today marks 43 years since the U.S. Supreme Court guaranteed a constitutional right to an abortion. In Roe v. Wade, seven justices ruled that the right to privacy, protected by the 14th Amendment, encompasses the right to terminate a pregnancy.

Roe, which itself was a challenge to a Texas anti-abortion law, was the banner case in the fight for reproductive freedom in the United States, but it also created a deep divide that affects nearly every aspect of American politics, from elections to judicial nominations. Since 1973, the anti-abortion movement has built a groundswell of support for overturning Roe. In recent years, the movement has enjdoyed a tide of anti-abortion legislation making the procedure ever more difficult and expensive to access, though the measures skirt the line of constitutionality.

Now, more than four decades after Justice Harry Blackmun wrote that Texas’ then-restriction on legal abortion “without regard to pregnancy stage and without recognition of the other interests involved, is violative of the Due Process Clause,” we find ourselves at another critical moment in the American fight for reproductive rights.

On March 2, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments for and against elements of House Bill 2, Texas’ omnibus anti-abortion law, almost two years after independent Texas abortion providers filed their first challenge to the law in an Austin federal court. The case is styled Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, and it challenges the most restrictive package of anti-abortion laws in the country. While Roe established that abortion is a protected constitutional right, the court has given states more and more power to regulate the procedure over the years. Since 1973, states have collectively passed 1,074 abortion restrictions, 288 of them since 2010 and the tea party’s rise to power.

In taking up Hellerstedt, the Supreme Court is expected to answer critical questions regarding how far states can go to regulate abortion. Before HB 2, Texas had more than 40 legal abortion providers across the state. Since the law passed, those numbers have been dwindling as providers struggle to comply with HB 2’s medically unnecessary regulations. Should the Supreme Court uphold HB 2, Texas will see the number of abortion clinics drop from 19 to just 10, which experts predict will have a devastating impact on access to abortion, not only in Texas but across the country.

Texas has become a test case for anti-abortion laws, and if the HB 2 regulations are allowed to stand, anti-abortion lawmakers in other states are expected to implement similar restrictions, though many are already trying.

As a result, legal experts, as well as activists on both sides of the abortion debate, see this case as the most important in a generation. So how did we get here, to a turning point in a legal and political journey that spans four decades and will set the stage for the next generation of abortion rights — or lack thereof — in the United States?

First comes Hyde.

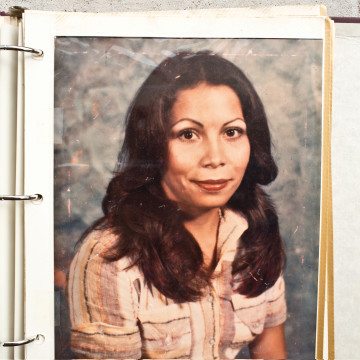

In 1976, a mere three years after Roe, Congress passed the Hyde Amendment, considered the first abortion restriction designed to eliminate access to the procedure. The measure, still on the books today, bans federal funding for abortion through programs like Medicaid, except in the cases of rape, incest, or if a pregnant person’s life is in danger. The impact was almost immediately devastating, as the amendment forced poor women to turn to unsafe methods in order to exercise their constitutional right to an abortion. Rosie Jimenez, a Texas mother and college student living in McAllen, was the first person known to die from an illegal abortion after Hyde, barely three months after it took effect.

The Supreme Court ultimately upheld the Hyde Amendment in a 1980 case known as Harris v. McRae, writing in its majority opinion that “[the] financial constraints that restrict an indigent woman’s ability to enjoy the full range of constitutionally protected freedom of choice are the product not of governmental restrictions on access to abortions, but rather of her indigency.”

McRae was the first post-Roe abortion case that set us down a path of targeted limits on abortion, many of which disproportionately affect poor women, said Jessica Pieklo, a constitutional law expert and senior legal analyst at RH Reality Check, a nonprofit reproductive rights news outlet.

McRae “sets the premise that lawmakers can pick and choose which patients have access unequivocally to abortion care,” said Pieklo. To put it more bluntly, she said, the court ruled that “abortion may be a fundamental right, but Congress can still screw with it with statutory funding.”

1992: The year the Supreme Court walked back Roe’s trimester-by-trimester framework and gave the states more power to regulate abortion.

The 1980s and early 1990s saw a wave of Christian conservative political uprising, and in his 1986 State of the Union address, President Ronald Reagan called abortion a “wound in our national conscience.” Out of that conservative surge came state restrictions on abortion, and a crucial Supreme Court case that opened the door for laws like HB 2: Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey.

In 1992, the court took up Planned Parenthood’s case against Pennsylvania’s Abortion Control Act, which mandated pre-abortion counseling, a 24-hour waiting period, parental notification for minors, and that a wife inform her husband of her plans to seek an abortion prior to the procedure.

Casey mucked with Roe’s entire trimester-by-trimester framework, opening up an opportunity for states to begin enacting more laws restricting access to abortion.

Casey mucked with Roe’s entire trimester-by-trimester framework, opening up an opportunity for states to begin enacting more laws restricting access to abortion. In its majority opinion, the Supreme Court ruled that states could now impose health-related abortion restrictions during the first trimester in the name of persuading a patient not to obtain an abortion, but those restrictions could not create an “undue burden” on access. Specifically, the court upheld Pennsylvania’s mandatory counseling, waiting period and parental notification for minors as constitutional, ruling that these types of regulations inform a person’s choice. But, the court struck down the spousal notification requirement, ruling that it did create an undue burden for women with abusive partners.

Simply put, “the state can persuade, but not prevent,” according to Linda Greenhouse, constitutional law expert, legal professor and a Knight Foundation distinguished journalist at Yale University’s law school. She also covers the Supreme Court for the New York Times.

The ruling is described by legal experts as a compromise, preserving the fundamental right to an abortion established by Roe, but giving states more power to regulate the procedure.

“Casey was the first time the court expressly identified the state’s interest in protecting the unborn [or] advancing fetal life even prior to viability, so long as the regulation is not an undue burden,” Pieklo told the Observer. “Much of [Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt] will determine just how far that state interest, pre-viability, can go.”

That’s… great and all, but how does this relate to the current Texas case?

Think of Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt as a test of what the Court decided in 1992.

In March, almost 25 years after Casey, the court will take up two key parts of HB 2: the requirement that physicians who perform abortions obtain admitting privileges at local hospitals and the requirement that abortion facilities operate as hospital-like ambulatory surgical centers.

The state of Texas and HB 2’s supporters maintain that such measures are designed to protect the health and safety of patients, but abortion providers and the medical community argue that the law has nothing to do with safety and everything to do with closing clinics and cutting off access to abortion. Together, these two provisions have led to the closure of more than half of the state’s abortion clinics, and forced patients to wait longer — up to 23 days, in some cases — for appointments and obtain their abortions later than they wanted.

If the Supreme Court upholds HB 2 in its entirety, Texans living south and west of San Antonio would be left with no options for obtaining an abortion close to home, and will have to travel hundreds of miles for the procedure. For now, two clinics in McAllen and El Paso have been allowed to keep their doors open thanks to a temporary hold on parts of HB 2 issued by the Supreme Court back in 2014. The only clinics that have, so far, been able to comply with HB 2 in full — by operating as ambulatory surgical centers and employing doctors who have hospital admitting privileges — are located in the state’s largest cities, north and east of Interstate 35.

Two key questions left open by Casey are at play in Hellerstedt, Pieklo explained. The first: “What kind of justification do lawmakers need to put forward when they say an anti-abortion law is to promote patient health?” And the second: “What is the court’s role in second-guessing state legislatures on those justifications?”

The medical community has strongly opposed HB 2. Earlier this month, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Medical Association and other medical groups filed a legal brief arguing that the admitting privileges and ASC requirements serve no scientific purpose, place “medically unnecessary” demands on abortion facilities, and ultimately jeopardize patient health and safety by limiting abortion access.

“It has to be real,” Greenhouse said. “If the so-called health regulations have only a minimal relationship to health but impose a great burden, the court has to strike them down.”

“It has to be real,” Greenhouse said. “If the so-called health regulations have only a minimal relationship to health but impose a great burden, the court has to strike them down.” (For a detailed legal breakdown of the court’s Casey ruling, Greenhouse’s Yale Law Review article is a must-read).

The central message of Casey is this: persuade but do not prevent. Cary Franklin, a constitutional law professor at the University of Texas at Austin, puts HB 2’s admitting privileges and ASC requirements in the “prevent” category, flying in the face of Casey.

“Closing clinics doesn’t inform a woman’s choice,” or dissuade her from obtaining an abortion, said Franklin. Instead, as the Hellerstedt plaintiffs and abortion rights supporters have long argued, closing clinics prevents patients from having an abortion.

What does “undue burden” mean? It sounds like the court came up with a term it never clearly defined.

Pretty much. In 1992, the Supreme Court described abortion restrictions as unduly burdensome if the “purpose or effect is to place a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion before the fetus attains viability.” Pieklo calls that definition “murky” at best.

“Hopefully, [Hellerstedt] will answer for us what exactly that standard looks like,” she said.

In opposing HB 2, abortion providers and their attorneys argue that the law imposes a wall of obstacles for patients. In closing clinics, the law forces patients to travel. And travel expenses add up, as well as the cost of taking time off work or paying for childcare, they say. Without clinics south of the internal border immigration checkpoints in Texas, for example, undocumented patients are virtually trapped in South Texas. The only remaining clinic in the lower Rio Grande Valley will close if the court fully upholds HB 2. All of this, Hellerstedt plaintiffs say, constitutes an undue burden.

Conversely, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals stood with the state, accepting its argument that the closure of clinics, especially in El Paso, is not a “substantial obstacle” constituting an undue burden. The state maintained, for example, that patients in El Paso can simply cross the state line into New Mexico for a procedure.

That argument is ironic, Greenhouse pointed out, because New Mexico state law does not impose the same restrictions, which Texas insists are necessary for patient safety, on its abortion clinics.

“Excuse me?” she said. “As the saying goes, I was born at night, but it wasn’t last night.”

Are the Supreme Court justices really going to go for all that anti-science nonsense?

When it comes to how the high court will rule on HB 2, all eyes are on Justice Anthony Kennedy.

In June, when the Supreme Court issued an emergency stay on the full implementation of HB 2, Kennedy stood with the four liberal justices in the 5-4 vote, signaling at least that the majority of the Supreme Court is interested in addressing some of the unanswered questions on abortion restrictions.

Kennedy was one of three justices who wrote the majority opinion for Casey and crafted the compromise now before the court today. Of those three, Kennedy is the only one still on the bench, smack in the middle of the 4-4 judicial split on Roe.

Greenhouse said Hellerstedt presents Kennedy with an opportunity to stand by his 1992 ruling, which, though it narrowed the scope of Roe by compromising on how states can regulate abortion, ultimately upheld Roe. Greenhouse, and Pieklo, who wrote about Kennedy’s crucial vote for RH Reality Check in November, both read that as a good sign for the plaintiffs.

“Since the Carhart decision, anti-abortion lawmakers have gone bananas with junk science,” Pieklo said.

However, as Pieklo points out in her piece, 1992 was the last time Kennedy ruled in support of abortion rights. In 2006, he wrote the majority opinion for a 2006 Supreme Court case Gonzales v. Carhart, which upheld the federal Partial-Birth Abortion Act, which effectively banned most later-term abortions, as constitutional. In doing so, Pieklo said, Kennedy and the court gave a tremendous amount of power to the states by deferring to lawmakers’ judgment when “matters of scientific controversy” are at play. For instance, Kennedy accepted without question the idea that women experience a medically unfounded condition called “post-abortion regret syndrome,” coined by the infamous anti-abortion pseudoscientist Vincent Rue.

“Since the Carhart decision, anti-abortion lawmakers have gone bananas with junk science,” Pieklo said, because courts have less power to question the scientific and medical claims they make when passing anti-abortion laws. Hellerstedt, Pieklo said, will “test” Kennedy, “in terms of of the justification that lawmakers need to put forward when making these kinds of laws, and to what extent courts have to stomach them.”

On top of preserving the constitutional right to abortion, the Texas case is about personal dignity and human rights.

Kennedy has also set himself apart from his conservative colleagues in his interpretation of human dignity as a fundamental component of personal liberty, seen most recently in his opinion regarding same-sex marriage, but which he’s generally espoused on LGBT issues.

Generally speaking, dignity in the constitutional context means “the ability to live one’s chosen life,” Greenhouse explains, or as Pieklo put it, “the right to be free from the government telling you what to do at all times.”

In the context of reproductive rights, advocates, patients and legal experts see the ability to choose whether or not to have an abortion as part of that personal dignity and liberty, something that they hope Kennedy will agree with.

Ultimately, Greenhouse, Pieklo and Franklin see Hellerstedt as a defining case in abortion rights, slated to impact not just millions of patients in Texas, but across the United States. While in some states, courts have allowed abortion clinics to remain open by striking down restrictions like admitting privileges, others have upheld similar HB 2-like laws, forcing clinics to close. While not explicitly challenging the constitutional right to an abortion, as Roe did, the HB 2 case has the potential to eliminate access to the right guaranteed 43 years ago today.

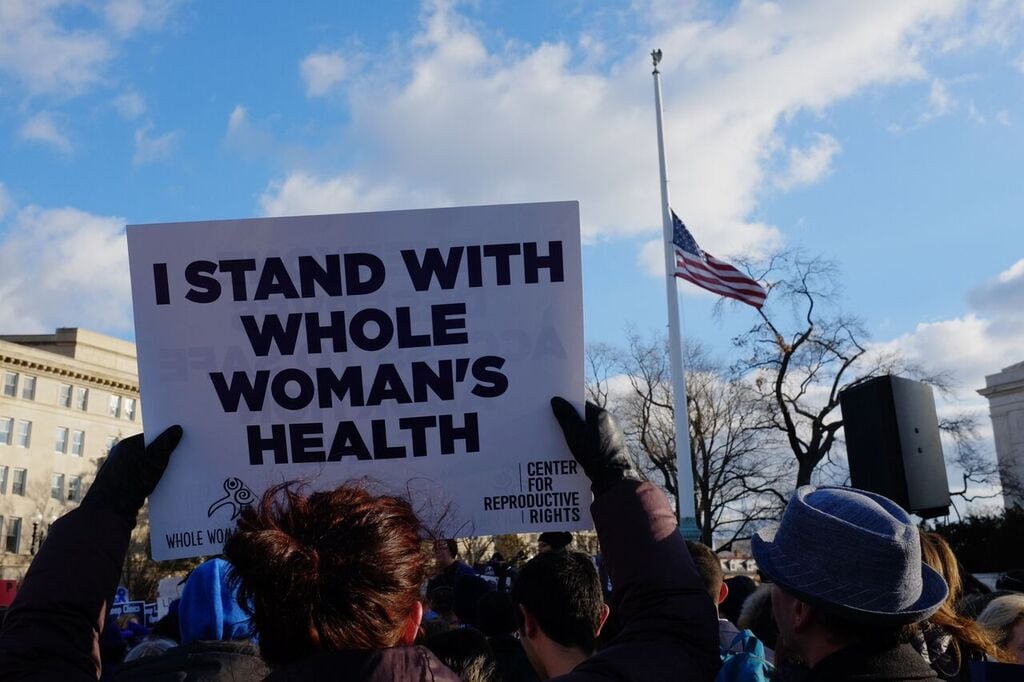

[Featured image of protesters during the 2013 legislative session by Patrick Michels.]

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.