Lawmakers Wrangle Over Fix for ‘Broken’ Foster Care System

Lawmakers clashed this week over whether Texas’ disastrous foster care and child welfare system can be fixed with more funding and higher pay for caseworkers, or simply better management.

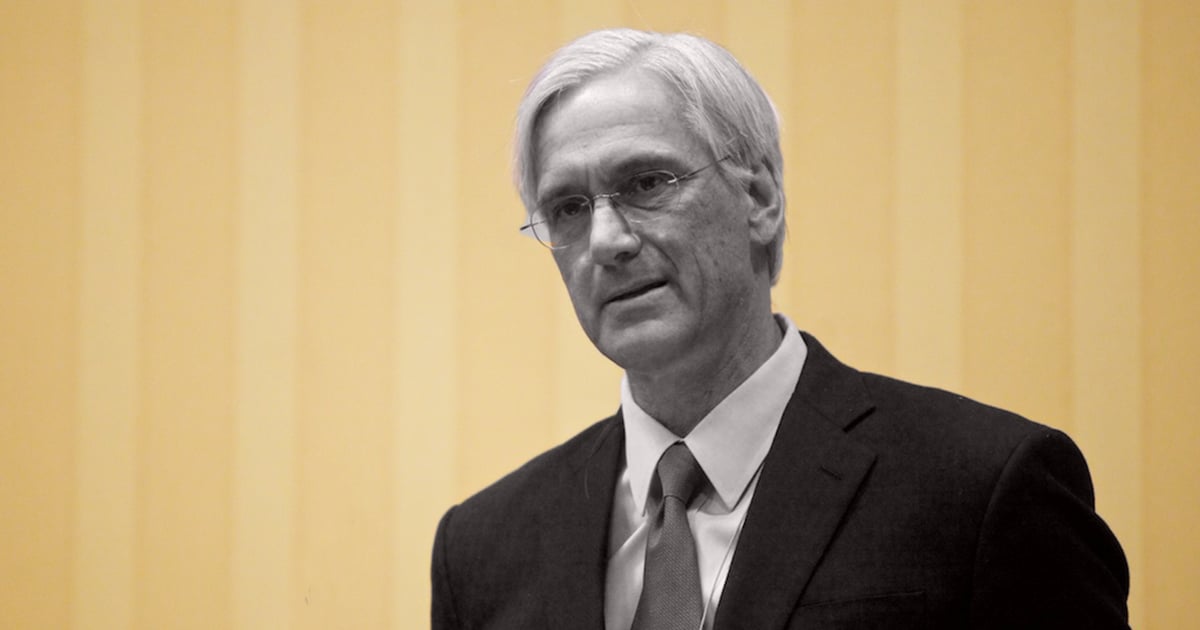

At a Senate Health and Human Services Committee hearing on Wednesday, Judge John Specia, the outgoing commissioner of the Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS), recounted the troubling facts from recent media reports. Foster care caseworkers are handling exorbitant caseloads, sometimes well beyond the the number recommended by child welfare experts, and children in state care are being assigned to, or sometimes left in, dangerous homes.

Madeline McClure, executive director of the nonprofit child welfare organization TexProtects, told committee members that between 2010 and 2015 more than 10,000 children in CPS care were abused again after state investigations.

“This is a measure of the system’s failure,” she said, calling the abuse “reprehensible, and pretty much unforgivable.”

High caseloads, low pay and extreme stress contribute to the chronic turnover among state Child Protective Service (CPS) workers, Specia said. The state spends $54,000 to train each new caseworker, but only pays them between $32,000 to $36,000 annually. Specia said caseworker turnover hovers at around 20 percent.

Texas, he said, must determine “what is appropriate to do the work and take care of children, and then fund that appropriate caseload.”

Not only are caseloads high, but the cases are getting more difficult as the number of “high-needs” kids — those who have emotional problems, a severe mental illness, medical needs or disability, or exhibit aggressive behavior — is increasing. About 5,500 of the 30,000 kids currently in state care are high-need, and researchers at the Stephen Group, a consulting firm hired by DFPS, recently found that those kids stay in the system for up to four years, two times longer than their healthier counterparts.

Among the many problems facing the system, Specia said, is the fact that foster families lack in-home training and services to take in high-needs children, which means it can sometimes be impossible to place children in secure homes. As a result, kids are funneled into expensive residential treatment centers “beyond medical necessity,” he said. And costs for that housing are on the rise: In 2015, DFPS spent $71 million to treat and place high-needs foster kids, up from $52.2 million in 2012.

Residential treatment centers “should not be warehouses,” Specia said. “They need to be places where a child receives a high level of treatment, and then be moved out.”

In a statement released during Wednesday’s hearing, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick praised the 2015 Legislature for increasing DFPS funding by $230 million. Nonetheless, the state’s foster care budget is projected to have a $40 million shortfall in the next fiscal cycle.

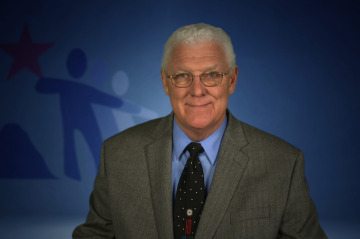

During the hearing, the committee’s Republican state senators discussed reallocating state money and restructuring management rather than increasing funding, while committee chairman Charles Schwertner questioned how great a role caseworker pay plays in turnover.

Democrats suggested that salary increases and better funding for early intervention would save money in the long run.

“I would submit to you that [CPS worker] pay has something to do with” turnover, said San Antonio Democrat Carlos Uresti. “Even if we lower the turnover rate by 5 or 10 percent, we will save money and we will save kids’ lives.”

According to DFPS, 12 percent of Texas children reported to the state to have been abused or neglected do not get the services they need. Another 8 percent of children were not promptly removed from their homes despite reports of abuse or neglect, and another 8 percent are returned home too soon. Children in all three of those categories, DFPS data shows, were abused or neglected again within 12 months.

A 2014 Observer investigation found that 14 children died from abuse and neglect while in state custody in fiscal year 2013. In the years since, the deadly failures have continued: A Dallas Morning News report from early April detailed the story of Leiliana Wright, a four-year-old who was beaten to death after CPS grossly mismanaged her case.

In recent months, the department has lost five top leadership positions as child deaths, monitoring deficiencies and inadequate capacity have all made headlines. In December 2015, a federal judge declared the state’s foster care system “broken.”

Lawmakers are poised to see significant state budget challenges in the next legislative session, but Republican House speaker Joe Straus wrote in a letter to House members this week that the foster care system is “in crisis” and needs to be a “top priority” in 2017, when the Lege meets next.

“Ensuring the safety of children in the state’s care requires new policies and ways of thinking,” Straus wrote, “but will also require additional resources.”

On Wednesday, state Senator Jose Rodriguez, D-El Paso, said inaction is no longer an option.

“Every time we have a federal court telling us that we’re not complying [with standards], it ends up costing us money,” he said. “I know we’re all concerned about cost, but we always talk about how prevention that we could have funded could save a lot of money.”