Mine Games

With little more than a promise, the Texas Railroad Commission is trusting a struggling coal industry to pay for the cost of cleaning up old mines.

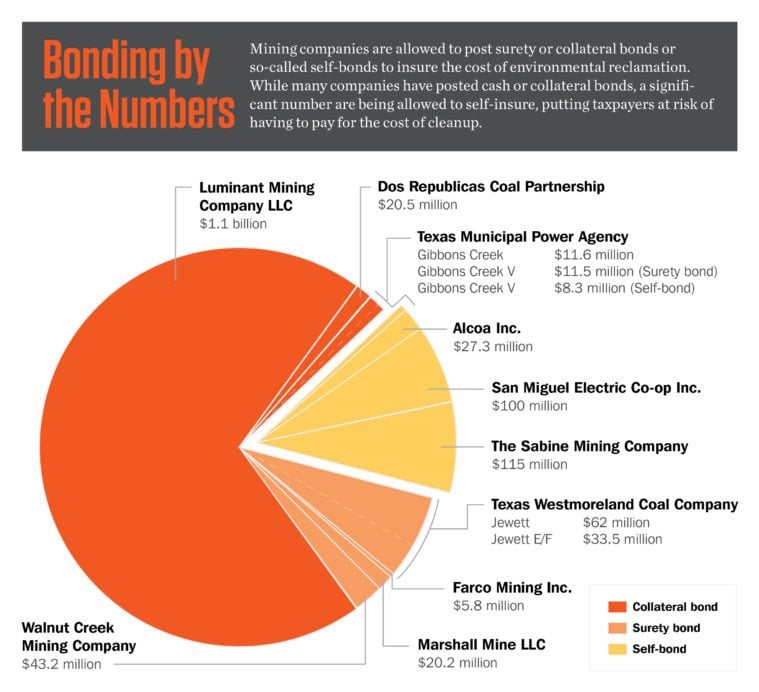

In mid-2014, Texas’ biggest utility, Energy Future Holdings, was about to file for bankruptcy, and Texas regulators suddenly had a big problem on their hands. Since at least the 1990s, the regulators had allowed Luminant, a subsidiary of Energy Future, to effectively issue an IOU for the $1.1 billion cost of cleaning up its coal mining operations in Central and East Texas. They had permitted Luminant to “self-bond,” which is essentially just a promise to pay.

With Energy Future Holdings in deep trouble, the Texas Railroad Commission, which oversees coal mining in the state, lurched into action. As the company worked to restructure its debt in bankruptcy court, the Railroad Commission scrambled to have the $1.1 billion for environmental cleanup set aside as part of the deal.

Eventually it worked. Texas regulators succeeded in strong-arming Luminant into posting $1.1 billion in collateral bonds, a more secure form of financial assurance.

But two years later, the Railroad Commission still hasn’t learned its lesson, according to critics. Despite the rapid decline of the coal industry, the Railroad Commission is currently allowing four other companies to self-bond, putting taxpayers and the state at risk of being left holding the bag should the companies go bankrupt. The Texas regulations are also flimsier than those in several other states, which means the Railroad Commission could be trusting financially weak companies to pay for the cost of environmental damage.

“Self-bonding at this point is nothing more than legal fiction,” said Clark Williams-Derry, director of energy finance at Sightline Institute, an environmental research nonprofit. “The notion that these companies can use money they make later for cleanup makes less and less sense when the industry is in decline.”

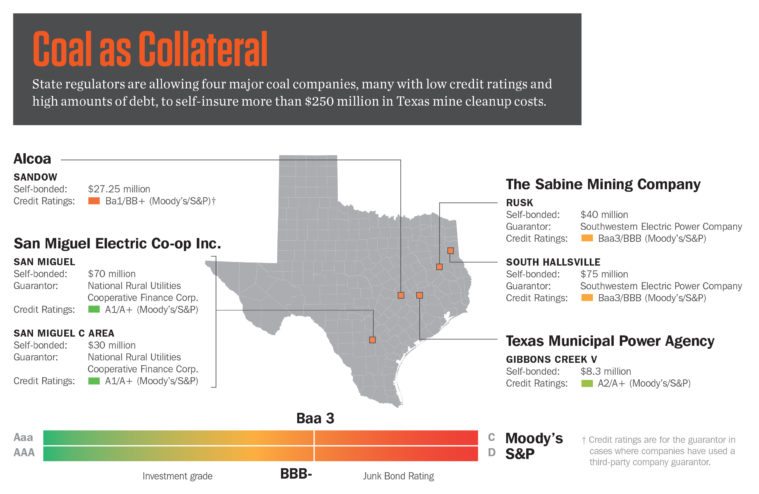

Typically, coal mining companies are expected to put away cash or bonds to assure regulators that even during economic hard times, they will have enough money for remediating the mines after they’re shut down. But in Texas, the Railroad Commission has allowed more than one-third of the state’s coal mining firms — Alcoa, Sabine Mining Company, San Miguel Electric Cooperative and the Texas Municipal Power Agency — to self-bond. The state currently holds more than $250 million in self-bonds.

As Luminant’s case shows, that’s a risky bet.

****

Hit by a one-two punch from cheap natural gas and a slew of environmental regulations, coal demand nationwide has dropped about 30 percent in the last decade. According to a March report by Moody’s Investors Service, 17 coal plants in Texas are at risk of shutting down, with 10 of them battling negative cash flows. As the pressure to clamp down on high-carbon energy sources increases, the downward spiral is expected to continue, according to analysts.

“We’re expecting [the coal market] to improve, but in the long run it’s definitely a downturn,” said James Stevenson, director of the North American Coal program at IHS Markit, a global industry research firm. “The companies’ valuations are low and a number of companies are in bankruptcy.”

Those challenges call into question whether coal companies should be allowed to self-insure. If mining companies go bankrupt, the self-bonding program could leave taxpayers with the bill for cleanup costs, a worry that led federal regulators to announce earlier this week that they would tighten the rules for self-bonding.

“If mining companies go bankrupt, the self-bonding program could leave taxpayers with the bill for cleanup costs.”

The risk is arguably higher in Texas. Four experts who reviewed Texas’ self-bonding regulations at the Observer’s request said they are flimsier than federal standards because they allow companies with low credit ratings and significant liabilities to self-bond.

“The bottom line is, the federal standards are themselves too weak,” said Williams-Derry. “The Texas regulations appear to be slightly weaker than the federal standards allow. They allow companies that should not be allowed to pass muster for self-bonding to self-bond.”

Industry officials say the financial tests in the self-bonding program are adequate to assess a company’s financial health.

“Self-bonding works as a tool,” said Ches Blevins, the executive director of the Texas Mining and Reclamation Association. “Texas has a very strong set of regulations on the books and has a very strong regulatory authority in place at the Railroad Commission.”

Ramona Nye, a spokesperson for the Railroad Commission, said the agency’s rules on self-bonding qualifications are “clear.”

“If a company cannot meet the requirements for self-bonding, that company must provide another form of acceptable financial assurance under our regulations,” she said in an email.

Nye did not provide more detailed responses to the Observer’s questions about the financial tests the Railroad Commission employs to determine whether a company can self-bond.

****

After almost a decade-long campaign by environmentalists, Congress passed the federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act in 1977. The law set minimum standards for state regulation of strip mining and reclamation.

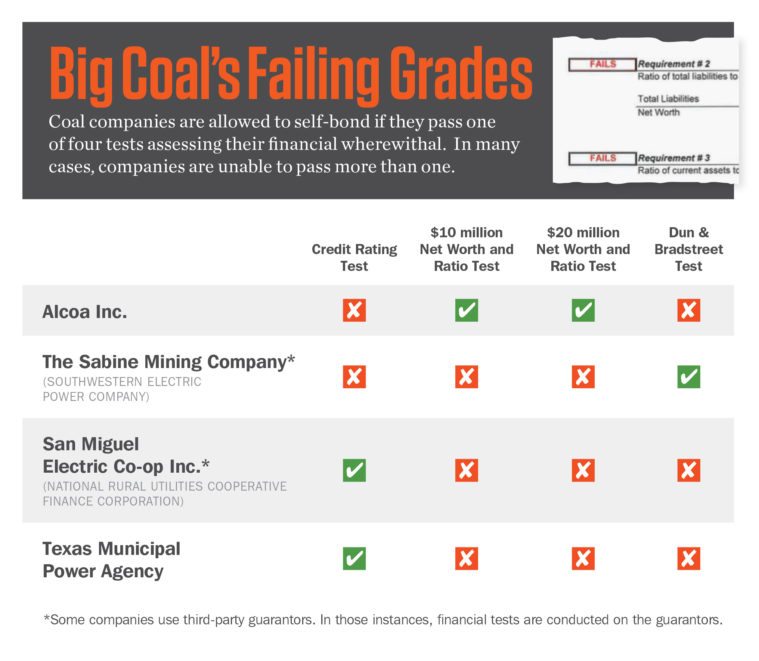

The law also stipulated that a company had to meet one of three tests to self-bond: a score of A or higher from credit rating agencies and a low amount of liabilities with either $10 million or $20 million in assets.

But those standards have repeatedly failed to detect mining companies on the brink of financial collapse. In Wyoming, Indiana and Illinois — where state regulations mirror federal statutes — regulators allowed coal companies to self-bond until after they filed for bankruptcy. Peabody Energy and Arch Coal, two of the largest mining companies in the country, continued to pass the financial tests using a legal loophole: They shifted their liabilities to parent companies and self-bonded using subsidiaries.

On paper, the subsidiaries looked financially healthy. In reality, they were tied to a parent corporation in dire financial straits.

Regulators also rely on audited financial data in which companies list assets at their purchase price, even if those assets have lost value over time.

“Just because you bought it for a billion dollars doesn’t mean you can generate cash of a billion or that anyone will buy it for a billion,” said Williams-Derry. “The end result is that you can have your books look financially healthy even as your company is descending into financial chaos.”

But Williams-Derry and other analysts claim that in Texas, coal mining companies might not need loopholes to pass the self-bonding test.

Texas has created a fourth test, allowing companies to self-bond as long as they have an investment-grade rating from credit rating agencies such as Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s (S&P) and finances that are better than the industry median as reported by Dun & Bradstreet, a business credit agency.

“Just because you bought it for a billion dollars doesn’t mean you can generate cash of a billion or that anyone will buy it for a billion. The end result is that you can have your books look financially healthy even as your company is descending into financial chaos.”

Environmental advocates criticized the test on two counts. The first portion of the test requires that companies have a credit rating of Baa3 and BBB- or higher, which allows companies to be considered as long as they do not have junk-bond status. Further, the industry median criteria is unlikely to weed out financially weak companies when the entire industry is in decline, critics said.

“That was a mistake,” said Tom “Smitty” Smith, director of consumer and environmental group Public Citizen’s Texas branch. “When the industry is collapsing, comparing yourself to everyone else in the dying industry does not mean you’re healthy.”

Williams-Derry likened the Texas self-bonding regulations to a Chinese menu, allowing companies to pick and choose options.

“Whichever criteria you happen to pass, you’re good,” he said. “If you fail two of them, you can pass the third and if you fail three, you can pass the fourth.”

Since 2007, Sabine Mining Company has done exactly that. The company used Southwestern Electric Power, a utility company that buys coal from Sabine, as a third-party guarantor. Southwestern has low investment grade ratings — Baa2 from Moody’s and BBB from S&P. It has close to $600 million in debt and only about half that in assets. As a result, it fails the first three financial tests.

But because it passes the weaker fourth criterion, the company has been allowed to self-insure the $115 million it’s required to post for reclamation purposes.

The agency “should not have approved these Texas rules,” said Mark Squillace, a University of Colorado professor who specializes in natural resources law. “They are less stringent than the federal rules.”

There are other cases of companies meeting just one of the four criteria, too. For instance, the Texas Municipal Power Agency, which operates the Gibbons Creek mine in Grimes County, has been allowed to continue self-bonding this year even though it failed three of the four tests. The company has a high grade from credit ratings agencies, but also carries an exorbitant amount of debt compared to its assets and net worth.

Texas regulators are relying almost entirely on ratings from Moody’s and S&P to determine the company’s financial wherewithal. Credit ratings agencies have failed in the past to detect systemic risk — before the housing mortgage crisis, for example.

The Railroad Commission reviews financials every year. When a company fails to pass at least one of the four tests, as was the case with the Texas Westmoreland Coal Company earlier this year, the Railroad Commission requires the company to post cash or alternative bonds. Last week, the agency switched Westmoreland to surety bonds.

But next year, if its finances improve, Westmoreland won’t need to meet any additional criteria in order to self-bond again. Texas regulations do not specify how long companies need to wait before they can apply to self-bond after they’ve been found noncompliant.

In 2014, Alcoa, a metal manufacturing and coal mining company that owns the Sandow mine near Rockdale, saw an increase in its debts, making it ineligible for self-bonding. A year later, however, after Alcoa purchased new assets, the Railroad Commission found it compliant and allowed the company to switch back to self-bonding.

Switching back and forth between self-bonds and collateral or surety bonds is “a real problem,” Squillace said. The case reminded him of Peabody, which set up a shell corporation and put enough assets in it to pass the self-bonding test.

“If some of these companies are playing fast and loose with the corporate structure laws, they could qualify for self-bonding even when there isn’t the kind of security the state might want,” he said.

******

At the federal level, pressure from environmental groups and the bankruptcy of major coal companies prompted the federal Office of Surface Mining to advise states earlier this month to not accept new self-bonds until the coal market stabilizes, which it believes won’t occur until 2021. In May, the agency, responding to a petition from WildEarth Guardians, a Western environmental nonprofit, started taking comments on the federal self-bonding statutes.

While the head of the Office of Surface Mining has said his department will meet with states to determine how to change the regulations so only financially healthy companies can self-bond, opponents of the program are pushing for it to be scrapped altogether.

Last month, the Railroad Commission’s executive director, Kimberly Corley, wrote to the Office of Surface Mining, charging that the WildEarth Guardians’ petition “exaggerates the consequences of current financial challenges in the coal industry.”

“We believe … that the current regulations provide adequate protection,” she wrote. “The Railroad Commission of Texas regularly monitors the financial health of companies that are self-bonded and our regulations provide for the prompt replacement of any self-bond instrument if we identify concerns about the company’s financial health.”

“If some of these companies are playing fast and loose with the corporate structure laws, they could qualify for self-bonding even when there isn’t the kind of security the state might want.”

Compared to states such as Wyoming and Illinois, where state government has been stuck with the vast majority of the reclamation costs, Texas has a better record. Wyoming regulators were able to wrangle only 15 percent of the cost of cleanup from Alpha Natural Resources and Arch Coal after they both filed for bankruptcy. In Texas, however, after Luminant’s parent company went bankrupt, the Railroad Commission was able to secure the $1.1 billion in collateral bonds to cover the entire cost of its reclamation obligations.

Public Citizen’s Smith said that happened partly because then-Railroad Commission Chairman Barry Smitherman was tough and partly because the $1.1 billion for reclamation was only about 2 percent of the total debt restructured under Luminant’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing.

Smith criticized the agency’s policy to continue to allow other coal companies to self-bond after its experience with Luminant. He pointed out that in 2014, although the company was floundering economically, it was able to meet the state’s requirements.

Smith said his group plans to point out the inherent risks of the self-bonding program to the Texas Sunset Commission, which periodically reviews state agencies and recommends changes to improve efficiency. In its latest report, the Sunset Commission identified as an area of concern the lack of adequate bonds by oil and gas operators for plugging old wells, but did not recommend changes to the coal self-bonding program.

Whether the Railroad Commission allows a company to self-bond or not is within the agency’s discretion, Smith said.

Luminant, he added, “was an example when the Railroad Commission stood up and did their job, and they should do it for other mining companies too.”