Quarantining Compassion

Texas Ebola policy may hamper efforts to fight the disease.

Texas has quietly joined the list of states implementing quarantines for health-care providers returning from Ebola-affected countries. Last week, Gov. Rick Perry’s office directed the Department of State Health Services (DSHS) to subject such providers to a 21-day quarantine, even if they have no symptoms of ebola. According to the governor’s office, it’s not a “strict quarantine.” However, it’s pretty darn comprehensive: Workers will not be able to travel on public transit, attend public gatherings, or provide patient care. Those who don’t comply will be subject to a “control order” from DSHS, enforceable by criminal prosecution.

Quarantine, said spokesman Chris Van Deusen of DSHS, “is pretty much just requiring someone to stay home.”

This policy, developed by the recently created Texas Task Force on Infectious Disease Preparedness and Response, is significantly stricter than what the Centers for Disease Control recommends. Healthy doctors and nurses will be quarantined, even though the task force acknowledges that the risk of such providers transmitting Ebola is “near zero.”

Despite this inconsistency, the DSHS press office has tweeted that the recommendations are “based in science.” Dr. Brett Girour, head of the task force, wrote in an email that the restrictions can “be increased or decreased based on individual circumstances,” and may be modified as new evidence comes to light.

“The CDC does not prohibit states from placing restrictions on [providers]” said Carrie Williams, spokesperson for DSHS. “Our guidelines strike a balance between what’s right for Texas and what’s reasonable for health-care workers returning from Ebola-affected countries.”

While it’s true that the CDC does not—and cannot—prohibit states from implementing such quarantines, that agency in fact recommends that quarantines for returning providers be implemented “based on a specific assessment of the individual’s situation.” If a provider got a needlestick while caring for an Ebola patient, for example, then he or she should be quarantined. The Texas policy includes assessing people individually, but then quarantining all returning providers—no exceptions.

The question of whether to self-isolate from infectious disease or help sick neighbors is an old one.

A policy of subjecting returning doctors and nurses to medically unnecessary quarantines may discourage them from going abroad in the first place. Providers need two weeks of training to fight Ebola, and a four-week commitment to do so. Tacking on three more weeks of quarantine means fewer American employers will let their workers volunteer, and fewer will go.

Girour wrote that the state and employers are responsible for addressing this issue. “The state should adopt policies that do not result in discouraging people from aiding Ebola patients,” he wrote, adding that employers could use sick leave, family medical leave and administrative leave to compensate quarantined workers.

Of course, mandatory quarantine itself will discourage providers from aiding Ebola patients.

Last week, United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon joined the chorus of world leaders speaking out against unnecessary quarantines for health-care workers. “Returning health workers are exceptional people who are giving of themselves for humanity,” said Ban’s spokesman, Stephane Dujarric. “They should not be subjected to restrictions that are not based on science.”

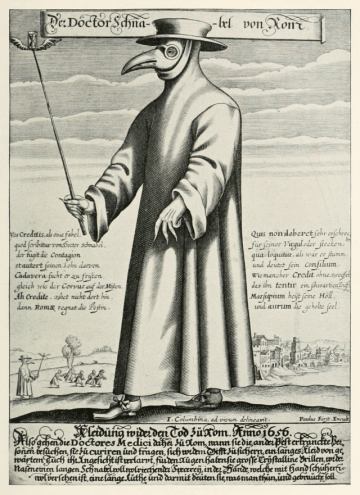

The question of whether to self-isolate from infectious disease or help sick neighbors is an old one. Boccaccio’s Decameron, a series of novellas written in Florence, Italy, during and after the plague epidemic of 1348, describes how surviving Florentines “tended to a very barbarous conclusion, namely, to shun and flee from the sick … thus doing, each thought to secure immunity for himself.”

Plague-scared Europeans nailed shut the houses of the poor and left the sick to die. Some scholars estimate that even so, a third of the world’s population was killed by plague in the 14th century. Quarantine—a word drawn from the practice of detaining foreign sailors arriving to Italian ports for 40 days—was enforced by police and governments in the era of plague.

People also opted to quarantine themselves. “A father did not visit his son, nor the son his father,” the Pope’s physician, Guy De Cheliac, wrote. “Charity was dead.”

Given this history, it’s perhaps not surprising that some Texas politicians are opting to nail the doors shut rather than follow the prudent advice of the CDC. Congressman Bill Flores (R-Waco) has called for mandatory quarantines and a travel ban from West African nations. Gov. Perry has also called for a travel ban. Experts say that such measures are not only epidemiologically unsound, but could seriously harm efforts to stop Ebola.

We have significant advantages over our Medieval counterparts. We have germ theory. We have personal protective equipment. We are dealing with a disease that doesn’t spread nearly as easily as plague did, and is therefore not as dangerous.

Although we have no cure for Ebola, we can provide effective supportive care. And we have a chance, as Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said, to stop the virus at its source.

Texans are already engaged in that effort. An unnamed nurse who returned from Sierra Leone to Austin in late October, before the new policy was in effect, has been quarantined. She was met by DSHS Commissioner David Lakey at the airport, and—“at Gov. Perry’s request,” according to a statement from the governor’s office—voluntarily submitted to a 21-day quarantine.

DSHS has not clarified whether the woman had an exceptional exposure to Ebola that would elevate her risk. Lakey concluded that “it was best for everyone for her to stay home, and she was amenable to that,” Williams said.

In the medical parlance, we would call this nurse “compliant”—more compliant than nurse Kaci Hickox of Maine, who has fought the blanket quarantines issued in East Coast states.

In a statement, Perry called the Texas nurse “heroic.” “Even now home in Texas, she continues to demonstrate her selflessness by agreeing to quarantine herself and further protect her fellow Texans,” he said.

Van Deusen also linked quarantine compliance to compassion. People at risk of developing Ebola “want to protect their family and community,” he said. So they stay at home.

Bit if all health-care workers returning to Texas from fighting Ebola abroad are subjected to a three-week quarantine, it will be a significant barrier to charity—and to global health. As Secretary-General Ban said, international health-care workers are needed to stop the virus “at its source.”

As modern and high-tech as Texas medicine is, it is also deeply unjust.

Ultimately, sending health-care workers abroad to countries where local providers have been decimated by Ebola is not simply a matter of charity or compassion. In this globalized world, it’s also a matter of self-preservation.

Sound health policy, based on science rather than on fear or politics, will protect Texans, not only with respect to quarantine and the provision of aid, but also as regards access to medical care here at home. Consider Thomas Eric Duncan, the only person who has died of Ebola in Texas. He was Liberian, and he twice sought care at a Dallas emergency room. As has been extensively reported, he was discharged the first time.

I cannot know, but I suspect that the fact that Duncan fell ill while uninsured—in a state that is home to 20 percent of this nation’s uninsured people, and whose health policies are notoriously disastrous for the poor—influenced the level of care he initially received.

As modern and high-tech as Texas medicine is, it is also deeply unjust. Do we really think that in a true epidemic here at home, the 5.7 million Texans who lack health insurance, for whom ER visits are a financial disaster, will report to doctors at their first sign of illness? Ebola is unlikely to sweep the nation, but influenza certainly could; it killed 20 children in Texas last year. In cases of infectious disease, health policy that is uncharitable to the poor and working class—not only the poor in Africa, but right here in Texas—puts us all at risk.

Everyone who is weighing in on this issue cares about Texas lives, whether they frame the issue as a matter of “public health” or “national security.” Helping American health-care workers get to Africa, sending material aid, avoiding unnecessary quarantines, and expanding access to care in Texas are sound health policies. Some could be called acts of charity. But in the end, all will make us safer.