Texas’ Failure on Birth-Certificate Gender Changes Is an International Problem

Texas, along with Iran, China and North Korea, is blacklisted by the U.K. for its undefined process for transgender people to change birth certificates.

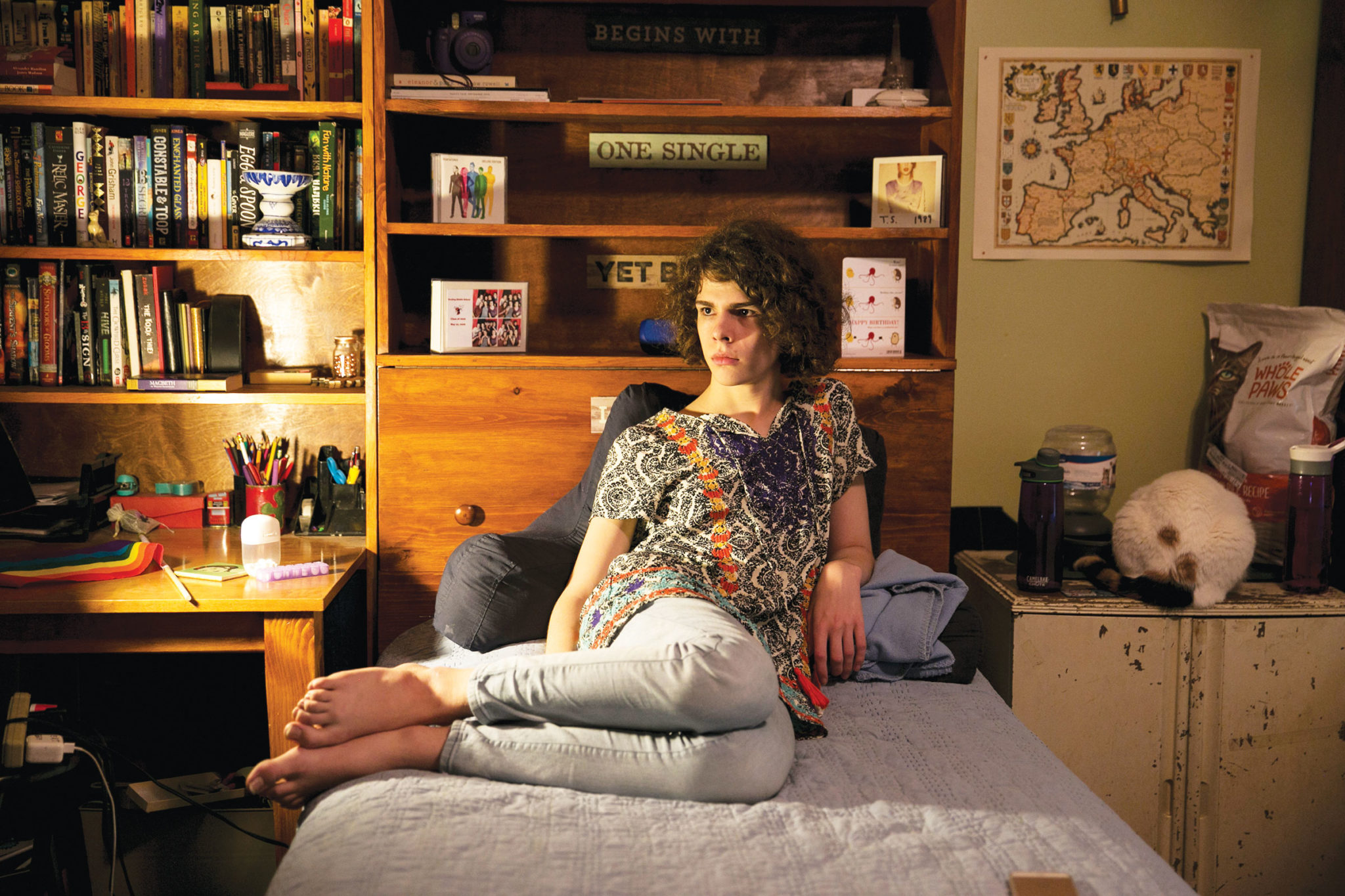

Thirteen years ago, Meghan Stabler was a senior executive at a large software company. It was a good job and to her colleagues she seemed successful, happy and outgoing. “But inside I was dying,” she says. “Typical trans story.”

Meghan was born Mark Stabler in 1963 in Yorkshire, United Kingdom. Around age 5, she says, she began feeling like she was in the wrong body. In 1990 she moved from the U.K. to Ohio with her then-wife for a tech job. Their daughter, Hannah, was born there in 1993.

A few years after the move, Stabler began thinking about transitioning, “but there was the pressure of knowing I had a family, career, and I worried about losing them,” she said.

By the time she relocated to Austin for work in 2002, her depression over living life as a man had become critical. One day she found herself sitting in her truck in a parking lot with a gun in her hand. “I knew then that my way out was to end it with a gun or be as authentic as I could.”

She began seeing a therapist, discussing the effects that transitioning would have on her family, job and friends. Her wife was uncomfortable with her new identity and the two began divorce proceedings in 2006.

Though she underwent gender reassignment surgery in 2007, the process wasn’t just physical. “The paperwork takes a long time. There are loans, lease agreements, bank accounts to change.” She began the arduous task of getting official documents altered to reflect her gender.

Stabler holds dual citizenship, and she says changing her U.K. passport was easy.

“I downloaded the forms, filled them in with my name and gender marker, and sent a photograph,” she said.

In Texas, there is no standardized way for trans people to change their driver’s licenses or birth certificates. And only a handful of courts routinely grant gender marker changes. Still, Stabler was able to convince a court in Williamson County to issue a court order authorizing her to legally change her name and gender marker.

With that, she was able to get a new driver’s license. Then there were mortgage documents and house deeds. “Every one of my fricking credit cards — and depending on the credit card company, they want a copy of the court order for the name change.”

Finally, there was the matter of her British birth certificate — the last piece of formal evidence that she was assigned the wrong gender at birth. Changing it would be “the final affirmation that you are congruent to how you perceive and present yourself to the world,” Stabler said, but she had been putting it off because she thought she’d never need it. “How often do you get asked for your birth certificate?”

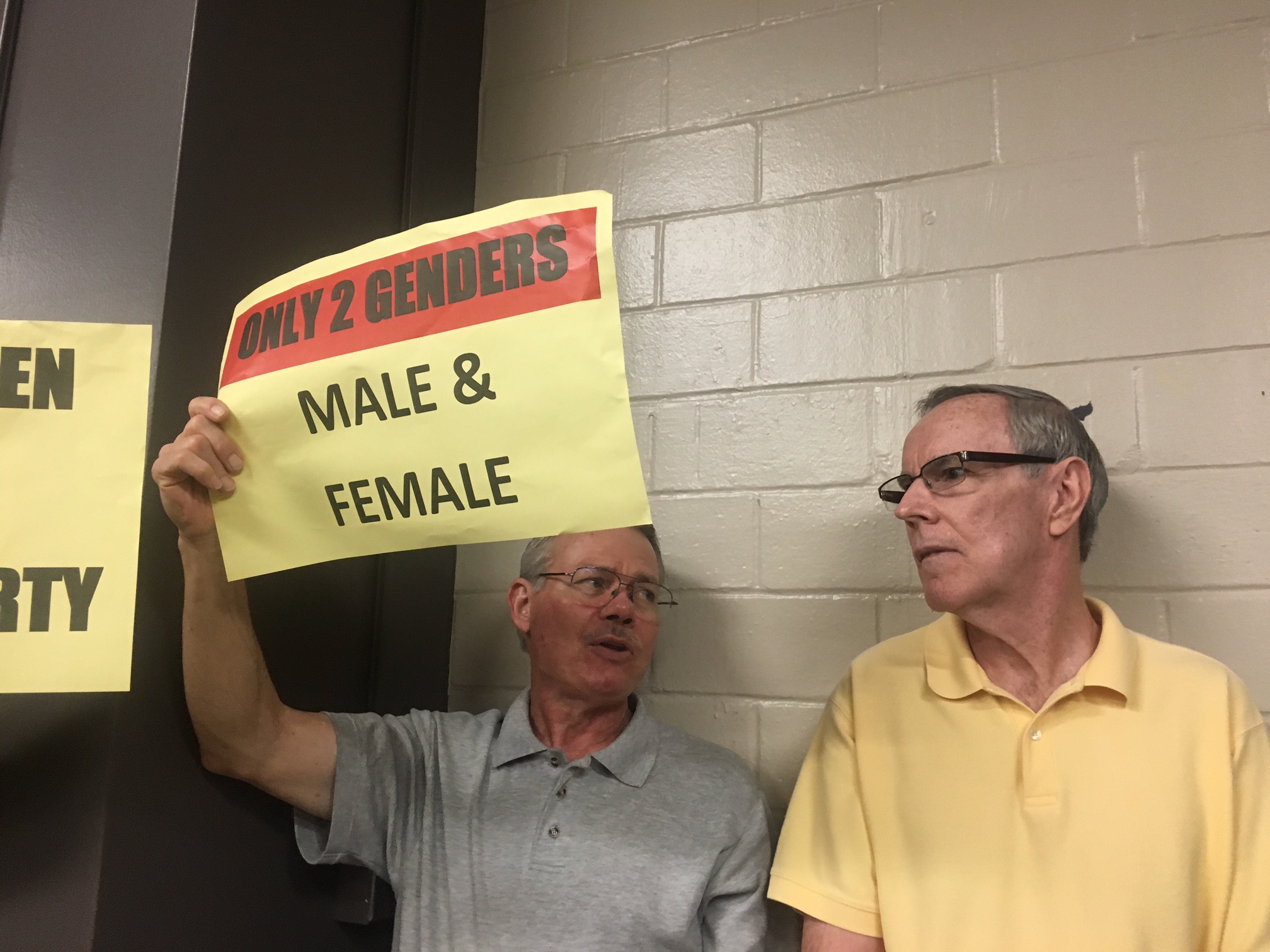

But legislation proposed by Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick added new urgency. In early January, Patrick unveiled his so-called bathroom bill, which requires Texans to use restrooms corresponding to the gender on their birth certificates. If she didn’t get hers changed, she could be legally forced to use the men’s restroom.

For a transgender person living in the U.K., getting a British birth certificate reissued is simple. For U.K. citizens living in certain places abroad it’s relatively straightforward, too, but Stabler would quickly discover that when it comes to trans rights, the U.K. government considers Texas a pariah state.

Britain has a well-established system for altering or reissuing documents to its trans citizens. If they live in the U.K., they must get approval from two doctors and apply to the country’s Gender Recognition Panel (GRP). For Brits living abroad, the U.K. secretary of state maintains a list of approved territories — 40 countries and 46 U.S. states — that have gender recognition systems comparable to the UK. Their doctors simply write letters to submit to the GRP. Stabler’s problem is that Texas does not appear on the list of approved territories.

Not surprisingly, among those not on the list are Iran, Afghanistan, China and North Korea. But Russia and Turkey are listed. While legally changing your gender marker in either of those countries is difficult, the process is enshrined in law, unlike Texas. There are just four states in the U.S. — Idaho, Ohio, Tennessee and Texas — that the British government doesn’t recognize.

A spokesperson for the U.K.’s justice department told the Observer he couldn’t comment on individual cases, and explained that in order to be listed a country or territory must have a clearly defined, statewide method for reissuing birth certificates to reflect a resident’s gender change.

Houston attorney Katie Sprinkle, who specializes in helping transgender people change their records, says Texas doesn’t have a specific statute allowing for gender marker changes, but that the Texas Health and Safety Code does allow a person’s “sex, color, or race” to be amended on their birth certificate if an error was made.

“To do that requires a court order and there’s no guidance on how to get one,” she said. “So it loops back around to getting in front of a friendly judge.”

Statistics obtained by the Observer in January from the Department of State Health Services show fewer than 1 percent of transgender Texans have updated their birth certificates.

Stabler says she finds it strange that many Southern states made the list. “But it’s also absurd the U.K. has that requirement in the first place,” she said. “I’m a British citizen, born in Britain.”

She can’t go to a doctor in another U.S. state because the overseas route requires residency in an approved state.

Stabler’s only option, therefore, is to fly back to the U.K., at considerable expense, to see two British doctors registered by the GRP: a gender dysphoria specialist who could give details of her diagnosis and a surgeon who could vouch for treatments or surgery she has had. “Both reports,” according to an email Stabler received from the GRP, “should be by British doctors. … Please note that medical reports by non-British doctors will not be accepted by the GR panel.”

She called one of the doctors on the list and was told they might write the report after a consultation over Skype — but she fears that would mean undergoing an invasive, embarrassing assessment over the internet with somebody she’s never met. “I just can’t believe I’d have to go through the burden of doing this when I have evidence in the form of a notarized letter from the surgeon who performed my surgery in Texas,” she says.

Stabler lives in the Austin suburb of Round Rock, where she works remotely for a tech company. In addition to raising her 5-year-old daughter, Edie, she finds time to sit on the board of the Human Rights Campaign. In 2012, she was a member of Obama’s LGBT Leadership Circle and was invited to the White House to witness the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

She tells me she’s exasperated with the British government and finds it incredible that a country keen to burnish its reputation on LGBT rights is putting up more roadblocks. And she can’t get any more information out of the GRP. “I can’t get them on the phone. They prefer email. And I’m going round in circles.”

She feels she’s being punished for the failings of the state she chooses to call home.

State Senator Sylvia Garcia, D-Houston, said it’s an “embarrassment” that Texas is one of only four states essentially blacklisted by the U.K.’s justice department. Garcia has proposed legislation that would allow transgender Texans to change their names and gender markers on their birth certificates without a court order, instead using a sworn affidavit from a licensed Texas doctor.

If successful, SB 1341 would not only help other transgender Texans, but probably lead to the state finally being listed by the U.K.

Stabler says changing her birth certificate is the key to feeling complete as a person, and would be a shield against Patrick’s anti-transgender “bathroom bill.”

“I believe you should have the ability, now the world is beginning to understand gender dysphoria and trans people a lot more, to change that record going back in time — to recognize who you are and who you were,” she says.