What Texas Lawmakers Can Learn from the Last Child Welfare Crisis

Texas’ child welfare system is caught in a cycle of crisis. Will lawmakers learn from their past mistakes?

When Daisy Perales arrived at the hospital in San Antonio in November 2004, she was unresponsive and malnourished. According to news reports at the time, she also had a fractured rib, head trauma and a lacerated spleen. She died, shortly after being taken off life support, on December 1. It was the day after her fifth birthday.

The girl’s mother, Ruby Jacquez, was eventually convicted of knowingly causing injury to a child and sentenced to 52 years in prison.

News of Perales’ death spread from Laredo to Amarillo. It was horrific, yet familiar. A few months earlier, 9-year-old Davontae Williams was found dead — his body bruised and severely emaciated — in his mother’s Arlington apartment. In June 2004 in San Antonio, 2-year-old Diamond Alexander Washington was beaten to death with a vacuum cleaner attachment by her mother.

All three families had previously been investigated by Child Protective Services (CPS). In Perales’ case, the agency had investigated her family seven times since 1998. The final case, stemming from reports of suspicious bruises and a broken arm in March, was still open when the child died. The horrific cases were proof positive that CPS was repeatedly failing to remove vulnerable kids from dangerous homes.

Buffeted by the horror stories, lawmakers pledged to fix CPS. Shortly after Perales’ death, then-Governor Rick Perry deemed CPS reform an emergency item in the 2005 legislative session. Senator Jane Nelson, the Republican chair of the Senate Health and Human Services Committee, took the lead on omnibus reform legislation that overhauled both CPS and Adult Protective Services. Budget writers funneled an additional $200 million to the agency to hire and train caseworkers, and reduce their staggering caseloads. Legislators also set in motion efforts to begin privatizing foster care.

“The system set up to protect our most vulnerable citizens has collapsed, and this legislation aims to rebuild its foundation,” Nelson said at the time.

But advocates warned that the reforms were flawed and came with almost no oversight. Indeed, in 2006, the rollout of the privatization pilot program was postponed indefinitely amid bickering between providers and lawmakers.

A decade later, legislators are back at the Capitol promising solutions to an eerily similar crisis. Recent high-profile child deaths and a scathing 2015 federal court ruling have spurred public outcry about the dismal state of child welfare in Texas. Governor Greg Abbott has declared CPS an emergency item and Nelson is promising yet another CPS overhaul to improve investigations of abuse. Legislators also want to expand “foster care redesign,” the bureaucratic name given to nascent privatization efforts already underway in North Texas.

“Texas spends less than half the national average on its children.”

Lawmakers have an opportunity this session to finally break the cycle of crisis, reform and complacency. But to do so, advocates say, the Legislature must learn from past mistakes, give CPS adequate, sustained funding and tread carefully with privatization.

For Madeline McClure, the founder and CEO of Dallas child welfare agency TexProtects, the main cause of the crisis is a stingy Legislature. Describing herself as one of the “last standing child advocates from the 1990s,” McClure has worked with lawmakers and child welfare officials through multiple crises over the last 20 years.

“I hear people say over and over again, ‘Well, we’ve been putting in money and throwing it at CPS, why isn’t it fixed yet?’” she said.

But that’s a misconception, McClure says. According to surveys from the Urban Institute and the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Texas spends less than half the national average on its children. Flushing the system with cash once a decade is simply not enough to make up for the growing number of children and regular budget cuts.

Indeed, the crisis a decade ago has its roots in budget cuts. In 2003, facing an enormous budget shortfall, the Legislature slashed $26 million from prevention services such as community-based parenting classes, crisis intervention and case reviews tailored to reduce child deaths. Lawmakers also sliced a total of $19.3 million from several foster care support services.

“They cut 50 percent of their prevention services, so that was pretty much a disaster,” McClure said.

In 2005, the Legislature pumped $200 million into CPS, but then made deep cuts again in 2011, amid the fallout from the recession.

“They also put a hiring freeze on the workforce,” McClure said. “It was really stupid. It was two steps back.”

Staffing levels dropped nearly 30 percent and caseloads on the remaining workers ballooned over the next two years.

This session, Senate and House draft budgets have CPS slated to receive from $260 to $268 million more than it did last biennium, but that’s far from enough. Officials with the Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) — CPS’ parent agency — say they need $1 billion to shore up the child welfare system.

Advocates are also wary about the Legislature’s zeal for privatization. Senate Bill 11, authored by Nelson and Senators Charles Schwertner and Carlos Uresti, seeks to expand a North Texas foster care privatization program and hand over case management to the private sector, as well. To some longtime child advocates, it’s the failed “solution” that keeps perpetuating the cycle of crises.

“We did this in 2005,” said Scott McCown, a former district judge and director of the University of Texas Children’s Rights Clinic, to a Senate committee in February. “All of our internal efforts immediately withered away and our workforce left. That’s part of the reason we have the capacity crisis we have today.”

The foster care redesign, also called community-based foster care, rolled out pilot projects in two regions — one in rural West Texas and one in urban North Texas — in 2013. Within a year, the West Texas organization opted out of its contract because it was $2 million in the hole and was denied extra funding from the Legislature.

Since the rocky rollout, ACH Child and Family Services, the nonprofit that oversees the seven-county region around Fort Worth, persisted through the financial shortfall and has managed to reduce abuse and neglect, increase stability in the lives of foster children and grow the number of foster homes in the region. But despite the program’s widely lauded success, the budget concerns that shuttered earlier efforts still haven’t been addressed. The nonprofit has invested $6 million of its own money to cover costs.

“As we look at how we want to deal with all this, we cannot kid ourselves that some sort of redesign is going to save money,” said Senator Kirk Watson, D-Austin.

DFPS requested $77.6 million to cover foster care redesign for the next biennium. Both chambers have proposed $71.4 million. But funding aside, some worry privatization can’t fix the system.

“If you’ve got problems at CPS, what SB 11 is going to do is pick up those problems and put them in the community,” said Will Francis, government relations director at the Texas chapter of the National Association of Social Workers. “Unless you really get those caseloads lower and you really do it thoughtfully, you’re just moving your outcomes.”

Francis and McCown also warn that sending millions of taxpayer dollars to private organizations comes with its own risks, such as conflicts of interest, increased removal rates and demoralizing effects on the remaining state-employed caseworkers.

“It’s easy to envision a scenario where a contractor makes a decision that looks to be an external success but ultimately conflicts with the best interest of a child,” Francis said.

McCown testified that financial incentives could lead private managing contractors to prefer placing kids in their own foster homes rather than with family members. Francis worries strict performance measures could pressure private caseworkers to release children from foster homes before they’re ready. Most frighteningly, both advocates predict that there could be no state CPS workforce left to fall back on if privatization fails again.

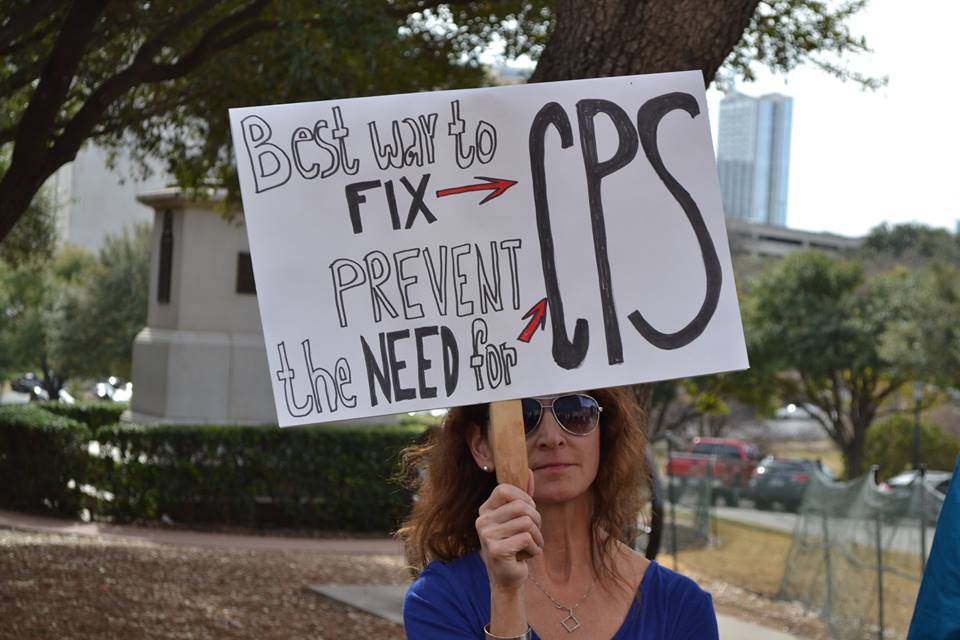

Lawmakers and advocates have come up with a slogan for child welfare this session: “Get it right.” Together, Francis, McClure, Uresti, Schwertner and approximately 100 others chanted it at a child protection rally on the south steps of the Capitol earlier this month. The simple phrase is hopeful, with 97 more days of the session ahead, but also implies a harsh truth — we’re in the midst of this crisis because they’ve gotten it wrong before.