Texas’ Maternal Mortality Rate Tops Any Developed Country. What are Lawmakers Doing About It?

Proposed solutions do little to address the underlying issue — health coverage for women.

State Representative Armando Walle, a Democrat from Houston and an Astros fan, has an analogy that he uses to describe the social safety net for pregnant Texas women: the protective netting that many major league teams have installed to protect fans from errant hits.

“There are many foul balls hitting moms in the face,” he said, “because that safety net is tattered.”

New mothers in Texas are dying of pregnancy-related causes at a higher rate than anywhere else in the developed world, “a life-or-death issue” that Walle says is “getting drowned out” by distractions such as the so-called bathroom bill. The state’s maternal mortality rate has doubled within a two-year period, according to a 2016 study, though experts say more research is necessary to explain the troubling spike.

Lawmakers have responded to the crisis by filing a smattering of bills this session that would continue research into maternal mortality and increase screenings for postpartum depression. But the proposals are piecemeal stopgaps for what many say is one of the underlying problems — access to health care.

“More than half of all births in Texas are paid for by Medicaid, but coverage for mothers ends 60 days after the child is born.”

Texas has the highest uninsured rate in the United States, and the state has rejected a federally funded expansion of Medicaid that would cover 1.1 million additional Texans. As a task force created by the Legislature in 2013 has discovered, it’s impossible to talk about the maternal mortality problem without addressing the health insurance problem. In a 2016 legislative report that found 189 maternal deaths in Texas from 2011-2012, the task force recommended extending health care access for women in the first year after birth. As the report notes, more than half of all births in Texas are paid for by Medicaid, but coverage for mothers ends 60 days after the child is born.

This session, however, only one bill picks up on the task force recommendation. Representative Garnet Coleman, D-Houston, has proposed a measure that would allow mothers to be screened and treated for depression for a year after birth if the child is enrolled in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

“This is the gold standard,” he said. “But everyone can see that it’s an expansion of Medicaid, and for some people here, if you spend another penny on Medicaid it’s no good.” Plus, the bill’s price tag — about $76 million over two years — will likely cause it to “die under its own weight,” he said.

Walle, who wrote the House bill establishing the task force two sessions ago, says he is focused on gathering more information on the causes of the jump in maternal mortality, in the hopes that having more research will eventually force the Legislature to take more decisive action.

“We have a history of doing things by crisis in Texas, instead of preventative health care,” Walle said. “We’re doing that with Medicaid and particularly the issue of maternal mortality.” His bill extending the end of the task force from 2019 to 2023 has made it out of the House Public Health Committee.

The Senate version of Walle’s bill, authored by Senator Lois Kolkhorst, R-Brenham, was considered in the Senate Health and Human Services Committee last week. Members also heard a bill by Senator Borris Miles, D-Houston, that would clarify the process for looking into maternal deaths. Currently, the need to redact all identifying information and enter cases into standardized forms has slowed the work of the task force, which is just starting to evaluate 2013 deaths.

Senator Charles Schwertner, the Georgetown Republican who chairs the Health and Human Services Committee, called the task force findings “very disturbing,” but questioned the study’s methodology. Both bills were left pending.

Lawmakers and advocates hope the Legislature can at least piece together enough individual bills to begin to address the crisis. But the success of any of these measures is uncertain, and even if all the legislation proposed this session were to pass it wouldn’t provide comprehensive and continuous coverage before and after pregnancy.

“A lot of members are doing small things,” said Representative Sarah Davis, R-Houston. “Obviously access to care is the most important factor. Women need access before their second trimester.”

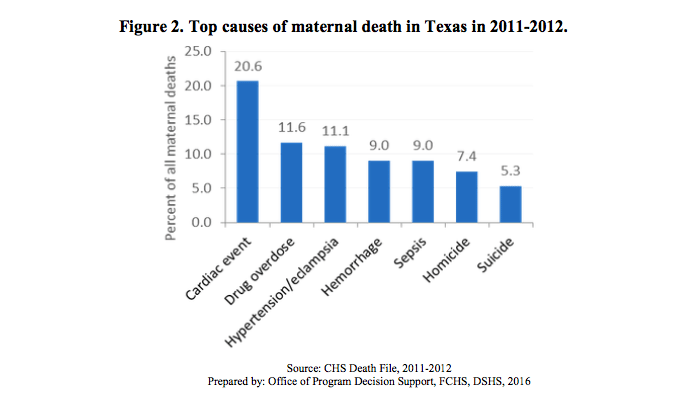

Davis is carrying legislation that would allow mothers to have a postpartum depression screening through their child’s Medicaid or CHIP plan, a measure she said was a response to the task force report. One in six new mothers in Texas suffers from postpartum depression and half the cases go undiagnosed, according to a recent report. Drug overdoses and suicide, along with cardiac events and high blood pressure, are the top causes of maternal deaths, according to the task force.

Advocates point to major family planning cuts in 2011 as one possible factor in the rise in maternal deaths, by severely reducing access to preventive screenings and other women’s health services. The closure of many Planned Parenthood clinic has forced women to drive hours to the nearest provider, said King Hillier, vice president of public policy and government relations at the Harris County Hospital District. Hillier was one of the first to notice anecdotally a large number maternal deaths in Houston; he worries the problem will only worsen if the Legislature does not deal with the issue of access.

“The key is prevention, prevention, prevention. We can either put money up on the front end or more expensively on back end,” Hillier said. “Medicaid expansion or granting postpartum women longer eligibility for Medicaid coverage would go a long way to address this issue.”