The Texas Misstep

A version of this story ran in the September 2013 issue.

Fifty years ago, a bizarre Western comedy called 4 for Texas starring Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin was released, proving once again that too much charisma can ruin a good thing—and that no one knew how to ruin a good thing better than the Rat Pack.

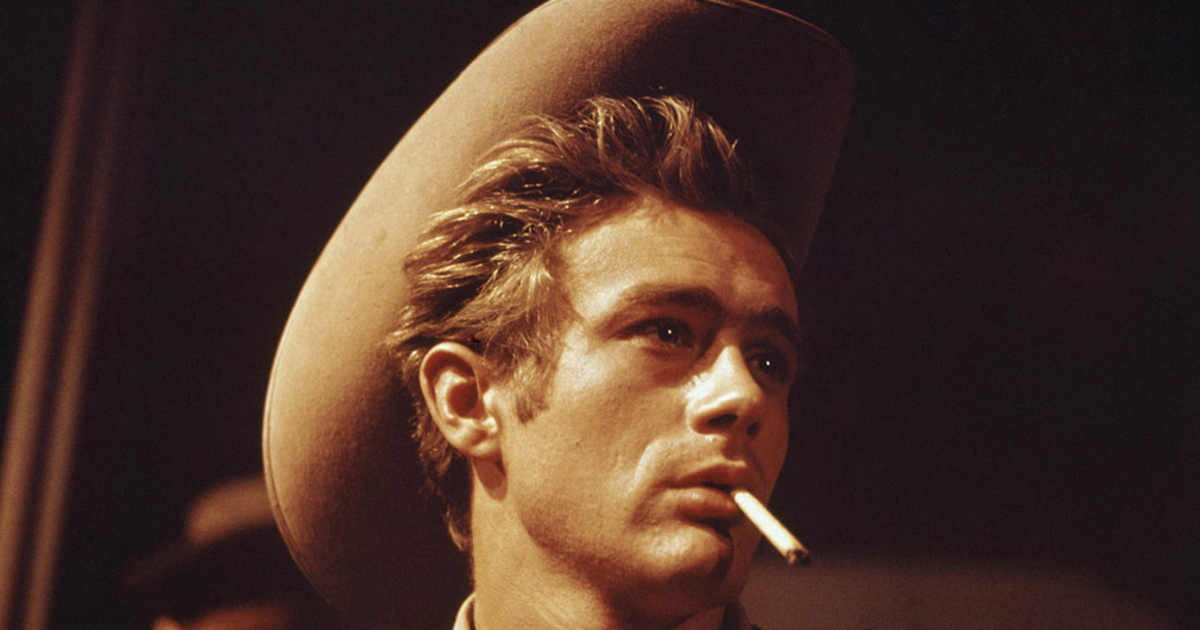

When they were in movies individually, the members of the Pack allowed themselves to actually act, to be human, to show vulnerability and depth. Together, they were a crass, back-slapping, prank-pulling boys club, a fraternity of self-regard in which vulnerability was the surest ticket to scorn, ridicule, and a distinct lack of ring-a-ding-ding. Send Martin out solo and you just might get a masterpiece like Rio Bravo or Kiss Me, Stupid. Get Sinatra by himself and he was capable of creating ruined anti-heroes in movies like The Manchurian Candidate and The Man with the Golden Arm. Put them together and you got self-indulgent nonsense like Ocean’s Eleven and Robin and the 7 Hoods. And 4 for Texas.

The Rat Pack en masse knew nothing about struggle; their whole shtick was convincing the world they had never even heard the word, and offering fans a chance to live charmed lives by proxy, if only for the length of a concert or a movie. But struggle was everything to 4 for Texas writer/director Robert Aldrich. He had chosen to forgo the riches of his New England youth to work his way up from a clerk position at RKO Pictures, and his greatest films, Kiss Me Deadly and The Big Knife, were about men struggling against enormous odds to achieve something like self-determination. So when Aldrich started shooting 4 for Texas in 1963 with Martin and Sinatra in the leads, he must have already known his story of money, sex and power, of shifting allegiances and questionable morality, was doomed.

The shame of it all is that it didn’t have to be that way. When Martin signed on to play Joe Jarrett, the smooth-talking lawyer-turned-criminal who invests $100,000 of ill-gotten money in a riverboat casino in Galveston, he had hoped to persuade either Robert Mitchum or Jimmy Stewart to take the role of Zack Thomas, the man he vies against. Unfortunately Sinatra got the role instead, and what could have been an ironic exposé of the relationship between capitalism and violence in the development of the American West—a world (not unfamiliar to us) where wealth buys you out of accountability—instead became a puddle-deep adolescent male fantasy full of easy money, easier women, gun fights, fist fights and absolutely no cops. It became a Rat Pack routine. In their Vegas stage shows, Martin, Sinatra and the rest were famous for sacrificing their vocal talent at the altar of inside jokes and high-roller banter. 4 for Texas is no different. Anything resembling depth or motivation is drowned by Martin’s finger-snapping esprit and Sinatra’s dispassionate Lord of All Creation routine.

And when you’re the Lord of All Creation, you don’t go small. You make sure the two biggest sex icons in the world are playing your leading women, no matter that they make no sense in the roles. In the world of the Rat Pack, women are trophies, and the best men get the best trophies. It’s a simple equation, and what it lacks in subtlety and substance it makes up for in brass and envy-inducing bluster. So we get Anita Ekberg, the unattainable ideal from Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, and Ursula Andress, the very first Bond girl, neither of whom could have looked more out of place in a Western if they’d been sent from Mars. No matter: Both looked like the kind of women people assumed slept with men like Sinatra and Martin.

Not that the women were relevant. Like all Rat Pack productions, 4 for Texas is pure proto-bromance. The women are immaterial and interchangeable; Sinatra and Martin love each other. Even when they marry their European paramours at the end of the film, their relationship with each other exudes homoerotic passion. Everything has worked out, Martin tells viewers, but if in the future their marriages should fizzle, “Zach and me figure we can always light out.”

It’s a line that sums up Zach and Joe’s truest loves, and Martin and Sinatra’s investment in the movie. They figure they can get by on their breezy personalities and magnetism, skimming the surface, ready to “light out” at any moment and committing nothing to the roles but their names and celebrity.

Sinatra in particular was a notorious diva on the shoot, cutting pages out of the script and failing to show up on days he was scheduled to work. Once filming was complete, Aldrich calculated that the singer had put in just 80 hours over the course of 37 days. The director considered legal action against Sinatra, both for failure to do the job he was paid for and for poisoning the set with his “negative and derogatory remarks.”

Leave the vulnerability and struggle to poor suckers (i.e., artists) like Aldrich, who would forever rue the day he stepped inside the scotch-soaked, bloodless world of the Rat Pack.