DNA Tests Undermine Evidence in Texas Execution

New results show Claude Jones was put to death on flawed evidence.

Hear Dave Mann’s interview with KUT’s Matt Largey on All Things Considered

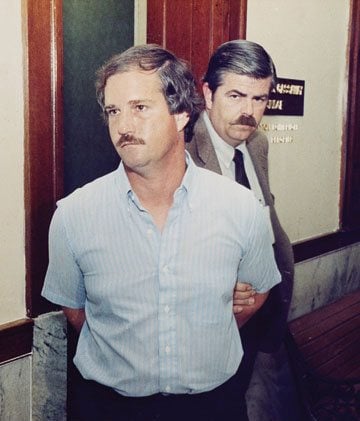

Claude Jones always claimed that he wasn’t the man who walked into an East Texas liquor store in 1989 and shot the owner. He professed his innocence right up until the moment he was strapped to a gurney in the Texas execution chamber and put to death on Dec. 7, 2000. His murder conviction was based on a single piece of forensic evidence recovered from the crime scene—a strand of hair—that prosecutors claimed belonged to Jones.

But DNA tests completed this week at the request of the Observer and the New York-based Innocence Project show the hair didn’t belong to Jones after all. The day before his death in December 2000, Jones asked for a stay of execution so the strand of hair could be submitted for DNA testing. He was denied by then-Gov. George W. Bush.

Watch Dave Mann’s interview with MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow

A decade later, the results of DNA testing not only undermine the evidence that convicted Jones, but raise the possibility that Texas executed an innocent man. The DNA tests—conducted by Mitotyping Technologies, a private lab in State College, Pa., and first reported by the Observer on Thursday—show the hair belonged to the victim of the shooting, Allen Hilzendager, the 44-year-old owner of the liquor store.

Because the DNA testing doesn’t implicate another shooter, the results don’t prove Jones’ innocence. But the hair was the only piece of evidence that placed Jones at the crime scene. So while the results don’t exonerate him, they raise serious doubts about his guilt. As with the now-infamous Cameron Todd Willingham arson case, the key forensic evidence in a Texas death penalty case has now been debunked.

“The DNA results prove that testimony about the hair sample on which this entire case rests was just wrong,” said Barry Scheck, co-founder of the Innocence Project, in a statement. “Unreliable forensic science and a completely inadequate post-conviction review process cost Claude Jones his life.”

Jones was 60 years old when he was executed on December 7, 2000—the last man put to death by then-Gov. Bush. The Observer and three innocence groups recently obtained the hair after a three-year court battle and submitted it for mitochondrial DNA testing.

That technology didn’t exist when Jones was convicted in 1990. But the DNA test had been developed by 2000, when Jones’ execution date was nearing. He requested a stay of execution from two Texas courts and from the governor’s office in order to test the hair evidence and prove his innocence. His requests were all denied.

Documents show that attorneys in the governor’s office failed to inform Bush that DNA evidence might exonerate Jones. Bush, a proponent of DNA testing in death penalty cases, had previously halted another execution so that key DNA evidence could be examined. Without knowing that Jones wanted DNA testing, Bush let the execution go forward.

Had the DNA tests been conducted before his execution, Jones might still be alive today. Scheck says these results, had they been obtained 10 years ago, probably would have led judges to throw out Jones’ conviction and grant him a new trial.

“I’m convinced that [Bush] would have granted this reprieve had he known about it,” Scheck told the Observer on Thursday. “I find it just astonishing that he wasn’t told. That’s a pretty serious breakdown in the criminal justice system.”

***

Claude Jones was no saint. Born in Houston in 1940, he was arrested numerous times and spent three stints in prison on robbery, assault and theft charges. While serving an eight-year sentence in a Kansas prison, Jones allegedly doused another inmate with lighter fluid and set him on fire.

But Jones wasn’t executed for his previous crimes. He was put to death for what allegedly happened on the afternoon of Nov. 14, 1989.

Jones and an accomplice named Kerry Daniel Dixon pulled into Zell’s liquor store in the East Texas town of Point Blank, about 80 miles northeast of Houston. They had a .357 magnum revolver given to them by a third man, Timothy Jordan.

Either Jones or Dixon remained in the pickup truck, while the other went inside and shot the store’s owner, 44-year-old Allen Hilzendager, three times and made off with several hundred dollars from the cash register.

The question is, which of them committed the shooting? Witnesses who saw the crime from across the street couldn’t positively identify which man they saw leave the store. The third accomplice, Timothy Jordan, would testify that Jones confessed to the shooting. (Jordan later recanted his testimony, claiming police told him what to say in exchange for a lesser charge. Jordan, Dixon and Jones had committed a string of robberies, though the liquor store heist was the only one that involved murder. Jordan was sent to prison for 10 years. Dixon was given a 60-year sentence.)

But Jordan’s testimony wasn’t enough to convict Jones of murder. In Texas, accomplice testimony can’t be the sole basis for a conviction; it must be corroborated by independent evidence.

At Jones’ 1990 trial in rural San Jacinto County, prosecutors offered only one piece of corroborating evidence—the strand of hair recovered from the liquor store counter.

Stephen Robertson, a forensic expert hired by the Department of Public Safety, examined the hair under a microscope—an inaccurate visual analysis that was common at the time. Robertson compared the hair with samples taken from 15 people who entered the store the day of the murder. He testified at trial that he believed the hair matched Jones. But he conceded, “Technology has not advanced where we can tell you that this hair came from that person,” he told the jury, according to court records. “Can’t be done.”

But in 2000, when Jones was fighting for his life, it could be done. On December 6, 2000, the day before the execution, Jones’ attorneys filed a last-ditch motion for a stay—in district court and with the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals—so they could submit the strand of hair for mitochondrial DNA testing. Both courts turned him down.

Jones’ last hope was Gov. Bush, who in December 2000 was embroiled in the Florida recount controversy that followed the presidential election. Bush had already overseen the execution of 151 people during his governorship, but he’d also expressed support for DNA testing. Earlier that year, Bush had granted a 30-day stay to Ricky McGinn so that DNA testing could be conducted on key evidence in the case. (The tests would prove McGinn’s guilt and he was executed.) Bush, explaining his decision in the McGinn case to CNN in June 2000, said, “To the extent that DNA can prove for certain innocence or guilt, I think we need to use DNA.”

But Bush was never told about Jones’ request for DNA testing. Through a public-information request, the Innocence Project obtained the Dec. 7, 2000, memo that lawyers in the governor’s office sent to Bush, briefing him on the circumstances of Jones’ pending execution. The four-page memo doesn’t mention Jones’ request for DNA testing. Rather, it describes the disputed hair evidence as “testimony from a chemist employed by DPS that the hair samples taken from the crime scene matched those taken from Jones.”

The memo from the general counsel’s office concludes, “At this time, I do not recommend that a reprieve be granted.” Jones was executed a few hours later.

But the strand of hair survived, tucked away in a box in the San Jacinto County courthouse for years.

In fall 2007, the Observer, the national Innocence Project, the Innocence Project of Texas and the Texas Innocence Network filed a lawsuit to obtain the hair for DNA testing.

The county district attorney’s office fought release of the hair sample and announced its intention to destroy it. But in June 2010, Judge Paul Murphy ruled in favor of the Observer and the innocence groups, and ordered prosecutors to turn over the remaining hair evidence for DNA testing.

Anti-death penalty advocates had hoped that the Jones case would provide the first-ever DNA exoneration of an executed person. While quite a few death penalty cases have been called into question, including several in Texas, no executed prisoners have been proven innocent by DNA testing, widely considered the most reliable form of forensic evidence.

Instead, Jones’ case now falls into the category of a highly questionable execution—a case that may not have resulted in a conviction were it tried with modern forensic science. In that respect, it’s much like the case of Cameron Todd Willingham, executed in 2004 for starting a house fire that killed his three children. Fire scientists now say the arson evidence used to convict Willingham was flawed. (The Forensic Science Commission will continue its investigation of the Willingham case at hearing on Jan. 7.)

Still, the revelations in the Jones case raise more questions about how Texas administers the ultimate form of punishment.

“My father never claimed to be a saint, but he always maintained that he didn’t commit this murder,” said Claude Jones’ son, Duane, in a statement released by the Innocence Project. Duane Jones didn’t know his father growing up and met Claude Jones when he was on death row. “Knowing that these DNA results support his innocence means so much to me, my son in the military and the rest of my family. I hope these results will serve as a wakeup call to everyone that serious problems exist in the criminal justice system that must be fixed if our society is to continue using the death penalty.”