Texas Police Departments Adopt New Crime Fighting Technology

A version of this story ran in the December 2013 issue.

Historically, civil libertarians and law enforcement watchdogs have reacted to innovations in police technology with skepticism if not alarm. Last year, for example, the ACLU published a report blasting unfettered use of automatic license-plate readers in places like Grapevine, where surveillance equipment scanned more than 14,000 plates a day, and the city had no plans to delete the data.

But a couple of high-tech solutions being rolled out in Texas police departments are proving exceptions to the rule. That’s because in addition to fighting crime, they have the potential to make police encounters safer for innocent civilians, not just officers.

One of the most dangerous police activities is the high-speed chase. The largest analysis of police pursuits found that almost a quarter of pursuits resulted in an injury or property damage, and that one in five injury victims was a bystander. But restrictive chase policies frustrate officers who feel their judgment should be trusted.

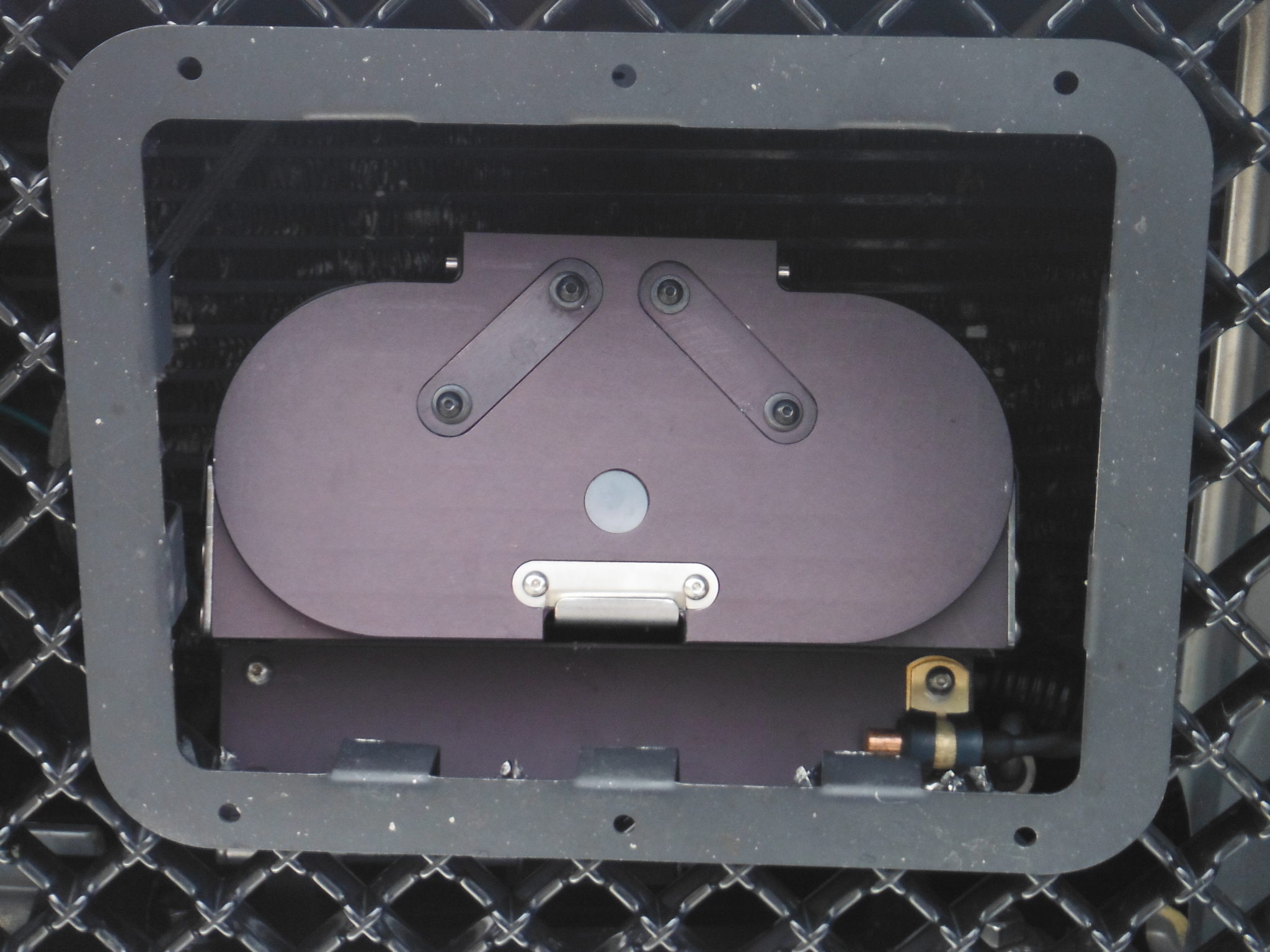

The solution? Be like Batman. As of March, a dozen patrol cars in Austin have been fitted with grill-mounted air cannons that fire GPS darts at fleeing vehicles. Deployed by a pursuing officer via keypad, the darts stick to the back of a suspect’s car, letting police discontinue the chase while continuing to track a suspect’s movements in real time.

The Austin Police Department is an early adopter. The maker, StarChase, says a “large handful” of agencies have installed the technology, including the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Office and departments in Iowa and Florida. It’s not cheap—each system costs about $5,000 and includes two darts, which can be refurbished and reused for $250 each. But it may be less expensive than the status quo. Austin police reported 135 pursuits in 2012, of which 22 ended in crashes. One of those crashes killed a bystander. The department says if the program is successful, it will seek grants to put the system in every patrol car.

Though it’s less cutting-edge, Houston, too, is using technology to address a pernicious police problem: civilian complaints. Since last winter, nine officers at the Houston Police Department have worn different types of body cameras in the field to help evaluate models for potential use. HPD recently confirmed that it plans to add 100 cameras by next summer, an expansion that will cost an estimated $400,000 including equipment and data storage. Though pricey, Houston police Chief Charles McClelland says the cameras may save money by quickly resolving Internal Affairs investigations. “You don’t have to spend resources to investigate frivolous complaints,” McClelland told the Houston Chronicle. “Sometimes when people make complaints, and they see themselves on video, they drop the complaints.”

But potential savings aren’t why groups including the ACLU cautiously support such programs. An October report from the group called police cameras a “win-win,” saying that while the group generally takes a dim view of expanded surveillance, “on-body cameras are different because of their potential to serve as a check against the abuse of power by police officers.”

Of course, any technology can be abused. The ACLU’s endorsement is contingent on the adoption of strict policies ensuring privacy and preventing tampering, policies HPD says it’s still developing. But the fact that two large police departments in Texas are investing in new ways to ease officer-citizen conflicts looks a lot like progress.

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.