Frank Pinkard stood before six legislators from the Texas Penitentiary Investigating Committee at the Clemens State Prison Farm in Brazoria County, revealing scars left from 39 lashes. Even after a year and a half, the braided rivulets ran over his thighs and buttocks, rising a centimeter above his skin.

It wasn’t the first time Pinkard had been punished for refusing to work since being convicted 13 years before at age 25. The Black farm laborer from Livingston had been shipped from Huntsville to a railroad camp, then to Rusk and two other prison farms before landing at Clemens, located on former plantation land about 60 miles south of Houston. State prison records show he received a total of at least 82 lashes for infractions like “laziness” and “mutiny.”

On a frigid February morning in 1908, Pinkard, along with eleven others, refused to continue digging a ditch after being forced to wade for days through icy water and mud in the same wet clothes. The warden himself administered the whipping.

“He broke the skin all over me every time he hit me. I bled and my clothes stuck to me for a month,” Pinkard told the six legislators on November 12, 1909.

Barely able to move, Pinkard soon resumed work. “We work as long as we can see how to cut [sugar] cane,” he said. It wasn’t only bucking work that could unleash brutal punishments. Refusing to greet a guard, speaking too loudly, or talking back could result in a lashing or other forms of violence. Every prison laborer who participated in the protest with Pinkard was punished, save one.

Only Alf Reid was spared, having been recently hospitalized after suffering nearly 100 lashes, Pinkard said. Still, Reid died two months later.

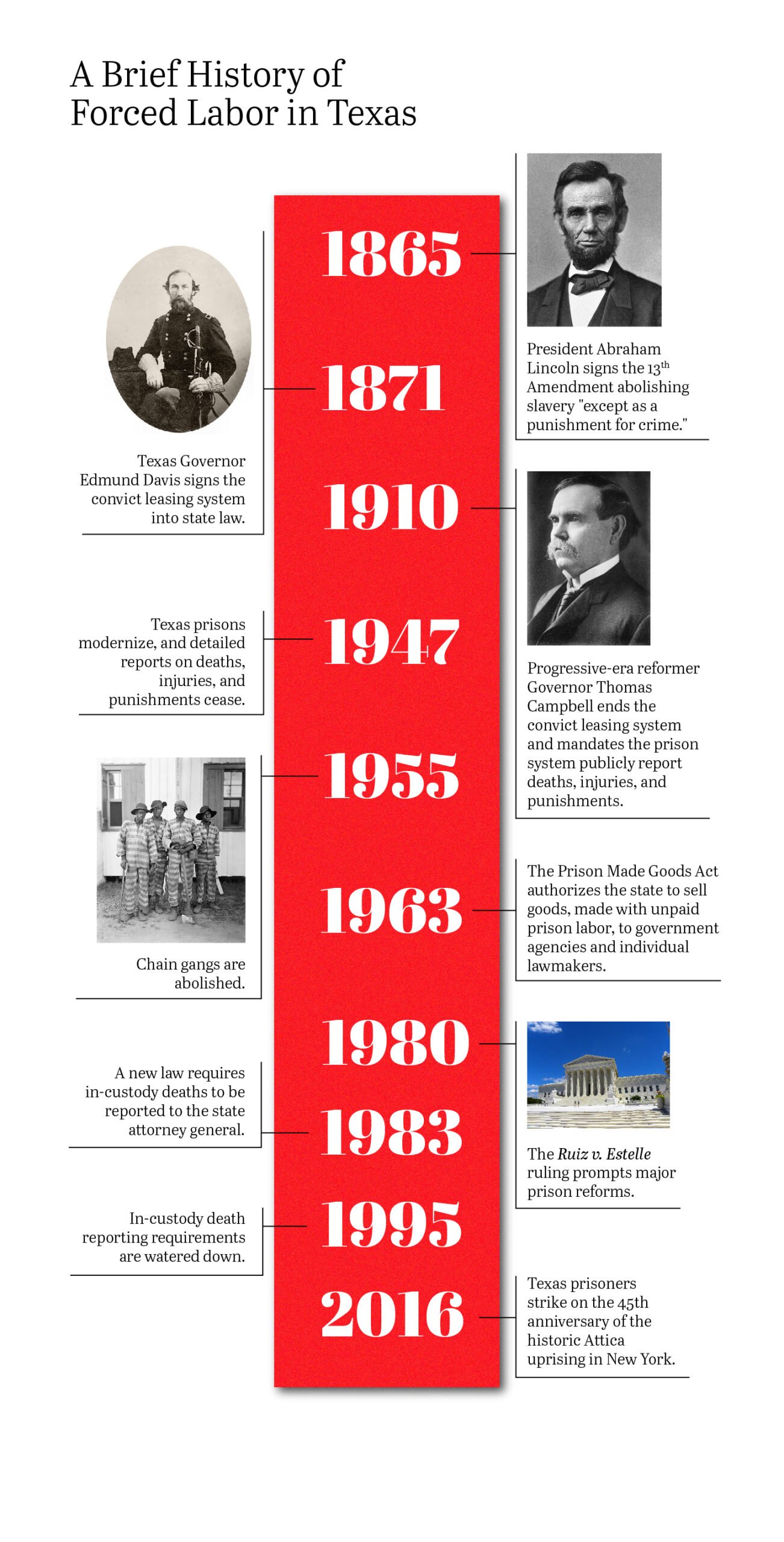

In 1910, members of the Penitentiary Investigating Committee, during the governorship of Thomas Mitchell Campbell, traveled by wagon and train to more than 20 railroad camps, industrial production units, and farms to interview convict laborers, a probe prompted by exposés in the San Antonio Express-News. After the committee released its report in August 1910, the Legislature effectively ended 39 years of convict leasing—a system in which the state hired out incarcerated people as virtual slaves to private contractors.

Instead, the state prison system would put incarcerated people to work on its own farms. Over the next decade, Texas amassed 139,000 acres for prison farms. More than 50,000 acres were purchased from ex-slaveholders who had become convict-leasing profiteers. The state would develop new prison units on these lands to run its own agricultural operations with captive labor. Most of these plantation prisons sprawled across what was known as the “Sugar Bowl District,” the same southeastern counties, including Fort Bend and Brazoria, where most enslaved Texans had been exploited before emancipation.

Today, 24 Texas prison units still have agribusiness operations. Nine are located on former plantations. Incarcerated workers harvest many of the same crops that slaves and later convict laborers did from 1871 to 1910. Like the previous owners, the Texas prison system still compels captive people to work its fields without pay. Guards on horseback monitor those who labor under the sun in fields of cotton and other crops. Texas prisons were finally fully racially desegregated in 1991, but Black Texans still account for one-third of the incarcerated—nearly triple their portion of the general population. Texas is one of only seven U.S. states that pay incarcerated workers nothing. Meanwhile, those incarcerated must pay for many essential items in the commissary. Their unpaid work is mandatory, a practice sanctioned by the U.S. Constitution’s 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

“The South really did not lose when it came to maintaining this form of free labor.”

This prison system of forced work is something of a black box. With free-world labor regulations inapplicable, it’s easy for the state to conceal work-related injuries and even deaths, leaving concerned citizens and journalists to cobble together information from inmate letters, lawsuits, and scant medical documentation. Shockingly, the Texas Legislature required far greater disclosure of work conditions, injuries, deaths, and punishments on prison farms during convict leasing and in the three decades after it was abolished than it does today. To uncover this, the Texas Observer spent months comparing thousands of pages of archived reports and testimonies from the late 1800s to the 1940s to contemporary court filings, state documents, and interviews with incarcerated workers.

After 1946, the prison system’s formerly detailed reports to the Lege abruptly excluded information about work-related injuries and deaths, around the time that Oscar B. Ellis took over as general manager of the system. Ellis served in that role from 1948 to 1961. Historian Robert Perkinson, author of Texas Tough: The Rise of America’s Prison Empire, said Ellis and his successor George Beto, the system director from 1961 to 1971, modernized prisons but demanded high levels of production from incarcerated workers under threat of punishment. Beto boosted profits under reforms that required state agencies to buy prison-made goods. Seeking to further their political careers, they diminished the annual reports to little more than “public relations materials,” boasting of the prison system’s agricultural and industrial output without mentioning its workers, Perkinson told the Observer.

Historic and modern statistics show that the death rates of the incarcerated remain similar to those reported to the Legislature nearly 80 years ago. At a rate of 4.7 out of 1,000 incarcerated people, the 2023 death rate in Texas prisons was only slightly lower than it was in 1946, when those detailed legislative reports ended. Out of a prison population of around 120,000, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) recorded 574 total prisoner deaths last year. In 1946, 22 out of 4,246 prisoners died in custody—a rate of 5.2 in 1,000. Harsher sentencing laws and an aging prison population may impact modern death rates, but criminal justice experts say the present lack of transparency makes it hard to discern the causes of the troubling frequency of prisoner deaths.

Since 1983, prison and jail officials have been required to report basic information on in-custody deaths to the Texas attorney general. Failing to report them is a misdemeanor. Compliance improved when those reports became public online, but they still contain scant details on the circumstances of death, making it difficult or impossible to figure out if fatalities were related to avoidable workplace injuries, heat exposure, or excessive punishments.

TDCJ officials today routinely cite incarcerated persons’ privacy as a reason to provide minimal information on in-custody deaths or injuries. The agency did not allow the Observer access to prison farms for this story and refused to disclose individual prison work assignments. TDCJ also denied requests for information related to disciplinary proceedings or alleged prisoner abuse. A TDCJ official said disciplinary information can only be released in very limited circumstances.

Michele Deitch, director of the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the University of Texas at Austin, told the Observer that today’s dearth of reporting requirements reflects a current criminal justice culture that is “punitive [and] secretive about what’s happening inside our facilities.” Deitch’s own research confirms the state supplies little to no information to the public on prisoner treatment or conditions. “The data that is required to be kept by statute doesn’t go into issues of safety or health,” she said. “It goes into things like how many people are incarcerated or parole rates or how much things cost. … It’s not providing us with a window into what’s happening.”

State prison officials today appear to have massively underreported the number of recent deaths related to heat, according to interviews, public health research, and lawsuits. Even in the free world, Texas workers die of heat exposure with disturbing regularity, a problem exacerbated by the climate crisis. Heat deaths are often missed—or concealed—if no one records a body temperature reading soon after death. TDCJ’s reports to the attorney general do not require such readings.

A TDCJ spokesperson told the Observer in April that there had been no heat deaths across the state’s approximately 100 prison facilities for a dozen years. That same month, a Texas prisoner and several advocacy groups alleged in a lawsuit that hundreds of people got sick and at least 40 people died of heat-related causes in TDCJ custody in 2023 alone.

Tommy McCullough, 35, died on June 23, 2023, of what the lawsuit said was heat-related causes. He got up to report to work and collapsed—temperatures in Huntsville’s Goree Unit reached 130 degrees Fahrenheit that day. (An autopsy report, obtained after original publication of this story, identified toxic levels of methamphetamines as the cause of McCullough’s death. Such a finding does not necessarily rule out hyperthermia.) Separate Texas Department of Insurance data obtained by the Observer shows that at least nine TDCJ prison employees reported injuries caused by extreme heat in 2023 that caused them to miss work.

Even though prison work requirements were supposedly narrowed in 1999 to only apply to those “physically and mentally capable of working,” incarcerated Texans still report that TDCJ officials put them to work regardless of health or physical conditions. In 2019, Jack Gutierrez, a 42-year-old incarcerated at the Terrell Unit, sued prison officials, alleging they refused to let people assigned to the cannery change jobs, even when a doctor had recommended the switch. Gutierrez alleged he and other men were told they had to work six months to a year before being considered for any transfer. That same year, another Texas prisoner filed a lawsuit alleging staffers at the Darrington Unit sent men to work without water for six days.

A TDCJ spokesperson told the Observer that prison officials follow doctor recommendations regarding work assignments and that “All inmates have access to water at all times.”

Operating a system of forced unpaid labor without strict reporting requirements appears to have allowed the prison system to perpetuate working conditions that still too often threaten incarcerated workers’ health and lives. Some advocates compare it to slave labor on some of the same land 200 years ago.

State Representative Carl Sherman, a Democrat from DeSoto who serves on the Texas House Corrections Committee, told the Observer: “Individuals who are incarcerated [are] being guarded by people who are wearing the same color clothing as during the Confederacy. The South really did not lose when it came to maintaining this form of free labor.”

In 2019, Alex Zuniga was housed in an isolation unit, known as “administrative segregation,” at the Darrington Unit (later renamed Memorial Unit). The land the prison sits on was once owned by Abner Jackson, Brazoria County’s second-largest slave owner, who divided more than 300 enslaved people between three properties. The Retrieve Unit, another TDCJ prison, later named the Wayne Scott Unit, also sits on land once owned by Jackson.

Typically, the incarcerated in solitary are kept in one-person cells for most of the day, but Zuniga said prison officials let him and the other men out a few days a week to do agricultural work. The first time he walked through the unit’s chicken house, he threw up, overwhelmed by the smell and cacophony of 80,000 birds in an enclosed space. (A TDCJ official told the Observer that prisoners in solitary are not allowed out to work.)

On a typical day, Zuniga, who is Mexican-American, said he would join a crew of about 50 others required to turn out for work around 7 a.m. “It’s kind of spooky because in the morning, you have a little bit of mist, and you have to wait for all that to clear out before you can step onto the farm,” Zuniga said. The men would be strip-searched, then walked or driven in wagons to their work area, where they would stand in a line in pairs and begin to clear out weeds with hoes or by hand.

To set the tempo for hoeing, one worker would call out, “Rock on it one, rock on it two, rock on it three.” After three swings, all the men stepped forward, and the hoes whistled through the air again.

Field workers for TDCJ still have the same basic marching orders as their predecessors: Work hard without pay for the benefit of the prison. Mostly men of color, in matching uniforms, still toil in fields producing tens of millions of pounds of crops, including raw cotton that the prison then turns into shirts, pants, underwear, and towels. Guards on horseback monitor them, and dogs are sent to track anyone who tries to escape.

During the convict-leasing era, white men were mostly sent to railroad camps or stayed in the Huntsville Unit known as “the Walls.” Black men, who were often convicted for petty crimes like mule or horse theft, were typically delivered to the sites of former plantations to work. In an 1874 convict camp report on the Lake Jackson Plantation, Inspector J.K.P. Campbell wrote that incarcerated African Americans were “unfit for any other pursuit” than farming. Thus, like their ancestors, Black captive laborers cultivated and harvested sugarcane and cotton on former slaveholders’ land under management systems similar to slavery.

Testifying to the Penitentiary Investigating Committee in 1910, John Lenz, one of few Black men locked up in the Walls before being transferred to Clemens farm in Brazoria County, stated that the industrial work assigned to white people in Huntsville was much less dangerous than what Black workers did on prison farms: “Give me 20 years solid here before I would get six months on the farm. I would be a dead man.”

The call to end convict leasing came in the Progressive Era of the early 1900s, when reformers targeted corruption and pushed to modernize many aspects of American society. Surprisingly, some segregationist Democrats in Texas played key roles in the reforms.

In 1906, when Thomas Campbell gave his first campaign speech as a Progressive-era Democratic candidate for Texas governor, he railed against “those who would debauch popular government and make it the instrument of avarice and greed.” A former Confederate Army captain and court-appointed manager of a bankrupt railroad, Campbell distrusted monopolies and sympathized with unions. He supported segregation in prison and elsewhere but opposed the use of the incarcerated “to enrich individuals and corporations.”

Under reforms Campbell promoted after becoming governor, convict leasing ceased. Texas’ incarcerated population remained unpaid for work, but their working conditions were recorded and publicized in detailed legislative reports. As part of the push for greater accountability and transparency, state law required “at the end of each month reports showing fully the conditions and treatment of the prisoners,” a requirement that remained effective through the 1940s.

Farmworkers made up half of the prison labor force throughout most of the 19th century. From 1900, that figure rose to at least three-quarters until prison manufacturing expanded in the 1960s.

From 1947 to 1983, very little information on prison deaths was disclosed. Then in 1983, Walter Martinez, a Democratic member of the Legislature from San Antonio, ended what he called a dark period in prison history by spearheading a new state law that required prompt reporting of all deaths of people in jails, prisons, and law enforcement custody. All agencies had to report any death within 30 days to the state attorney general’s office. But for decades compliance with the law was spotty.

In 1995, the Legislature loosened reporting laws by exempting TDCJ from reporting in-custody deaths to justices of the peace. That same year, then-Governor George Bush signed into law harsher drug penalties, expedited executions, and limited capital appeals while Congress passed the Prison Litigation Reform Act a year later, which made it more difficult for incarcerated people to sue jails and prisons.

Then, in 2003, Governor Rick Perry axed the state criminal justice auditor’s office. Tony Fabelo, the last independent auditor for the prison system, told Perkinson: “They wanted me to cook the books … and when I said no, the bastards fired me.”

According to current TDCJ policy, “trusties”—incarcerated workers with the lowest security requirements—are the only ones assigned to agriculture jobs outside of perimeter fencing in the 24 TDCJ units with agribusiness operations. But many with stricter security restrictions can be assigned to the “field force” to assist with agricultural tasks, under the supervision of guards. Their work assignments, any punishments, and details about their work-related injuries are no longer public information.

Agriculture today is a smaller part of TDCJ’s business portfolio than manufacturing, as prisoners are now tasked with producing everything from textiles to furniture. Agribusiness operations continue to provide food and raw material for clothing that the agency would otherwise have to purchase from private companies.

Last fiscal year, TDCJ reported earning more than $58 million from sales of products produced by the incarcerated. In 2022, the agency claimed its agricultural production saved the system $51 million. Its reports are silent on working conditions.

In the early years of convict leasing, farms and work camps often lacked physicians and medicine, based on historical reports. Working in the marshy Brazos River bottoms, prison farmworkers contracted malaria and tuberculosis, and the sickest had to be transported to Huntsville for treatment. Many died before arrival. Inspector Campbell reported in 1876 that he found 65 out of 185 prisoners ill on the Lake Jackson Plantation contract farm: “These men at the time had no medical attention. … Essential medicines were not at the camp. … The sick occupied the same building with the well.”

During convict leasing, the annual death rate among Texas prisoners peaked in 1878 at a staggering 147 deaths per 1,000 incarcerated, according to reports. But with increasing scrutiny, rates dropped to an average of 52 per 1,000 between 1882 and 1910.

The 1910 reforms that abolished convict leasing also called for all in-custody deaths to be reported to a justice of the peace (JP) who was required to independently examine bodies and investigate the cause of death. Prison employees who failed to immediately report deaths could face a misdemeanor charge and jail time of up to a year. Prison physicians also had to record and report, monthly, all cases and causes of illnesses as well as injuries they treated.

From the late ’20s into the ’40s, legislative reports listed each death, including the cause, date, location, and circumstances, sometimes specifying whether the death was work-related and including prisoners’ names.

For example, a 1940 report revealed three incarcerated laborers died from heat stroke while working on Brazoria County prison farms—in a year when local temperatures reached a high of 92 degrees. Last year, temperatures there topped 108 degrees.

Those regular disclosures allowed more opportunities for lawmakers and the public to examine and address in-custody work conditions in the past.

Nowadays, it’s not clear how often any independent official is called to review deaths in prison. A TDCJ spokesperson said that all in-custody deaths are reviewed by TDCJ’s Office of the Inspector General, which is described on its website as an independent office but reports to the state’s Texas Board of Criminal Justice, TDCJ’s politically appointed oversight board. Generally, prisoner autopsies are conducted under contract by the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), which considers them private medical information. Those autopsy and death investigation reports, which are generally produced for all prison deaths in Texas, might provide more information but are difficult to obtain. UTMB refused to release any prisoner autopsies in response to requests from the Observer, even though these documents are considered public records for deaths outside the prison system. TDCJ released copies that were almost completely redacted.

Since 1995, state prisons are no longer required to report all deaths to JPs. (And if an incarcerated person dies in a county jail of “natural causes” while attended by a physician, the death no longer has to be investigated by a JP either.) According to TDCJ policy, deaths are still reported to medical examiners in large counties that have them and to JPs in smaller counties that don’t.

The Observer obtained four autopsy reportsfrom one JP in Brazoria County whose territory includes five state prisons—presumably the only cases (out of 28 that the Observer requested) in which that JP was called in to review a prison death. (There is no medical examiner in Brazoria County, and county officials said they had no copies of prisoner autopsy reports in a response to the Observer’s request.) But even these four reports provided little detail.

In-custody death reports to the attorney general, which have been required since 1983 but were modernized in 2005 and made easily accessible online in 2016, include general biographical information about the person who died—name, date of birth, race, sex—and the medical cause of death. But the listed causes, such as cardiac arrest, often reveal little. The agency also includes a brief summary of how the death occurred, but very little information was recorded about the circumstances leading to deaths in dozens of reports the Observer reviewed for this story.

Texas’ death reporting requirements are actually better than those in many other states: It is one of only 15 states that publicly report information online about incarcerated individuals’ deaths in state prisons. However, Krishnaveni Gundu, the director of the advocacy group Texas Jail Project, said: “There is no enforcement. The system is just a passive database.”

“What we’re seeing is things like heart attacks, kidney failure, asthma attacks, death from diabetes complications…”

Unlike prison guards and other TDCJ staff, incarcerated laborers cannot file workers’ compensation claims when injured. And the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration does not investigate workplace injuries in state prisons. The best that incarcerated workers can do is plead with prison officials for a job assignment change.

In response to a records request, a TDCJ spokesperson provided the Observer with statistics on prisoners’ work-related injuries for fiscal years 2019-2023. According to the data, 160 incarcerated farmworkers were injured in 2023 while working in the fields, dog kennels, or horse barns, accounting for 7 percent of 2,323 total work-related injuries. But, unlike in reports published in the distant past, the nature and severity of injuries are not described in that data. The numbers also fluctuate significantly. In 2019, 586 incarcerated workers were reported injured working in the fields or with the dogs or horses—nearly quadruple the reported 2023 figure—accounting for 11 percent of 5,132 injuries.

The lack of legislatively mandated reporting on these injuries is particularly concerning given that incarcerated workers face increasingly hot temperatures. Those in agricultural jobs labor under the sun, exposed to the elements, and those with industrial or manufacturing jobs are often subjected to extreme heat even indoors.

In 2022, Julie Skarha, a public health researcher, estimated that as many as 271 Texans in prisons without air conditioning may have died of heat-related causes between 2001 and 2019, accounting for 13 percent of all deaths. (How many of those deaths occurred during or after work shifts is unknown.) Skarha based her estimate on an environmental analysis of the heat indices in the summers in specific locations where incarcerated Texans were reported to have died of other natural or accidental causes.

“What we’re seeing is things like heart attacks, kidney failure, asthma attacks, death from diabetes complications,” Skarha told the Observer. “Heat can cause all those things,” even if it’s not listed on the death certificate.

Robert Webb, who died during a scorching heat wave in August 2011, likely fell victim to hyperthermia, per an autopsy report obtained by the Observer through a Cherokee County justice of the peace. The pathologist from UTMB who was contracted to perform the autopsy noted that no one took Webb’s body temperature at the prison, but the air temperature in the unit at the time was 97.5 degrees fahrenheit, according to the report.

The vast majority of Texas prisons, including Brazoria County units located on former plantations, have partial or no air conditioning. Last year was the second-hottest in Texas history.

Many forms of punishment formerly used in the fields are now illegal, though captive laborers can still be punished for refusing to work. Lashings were banned in 1941, but those who refuse to work can face disciplinary actions and blots on their record that can jeopardize parole.

Solitary confinement hasn’t been allowed as punishment for breaking prison rules in Texas since 2017, and a TDCJ spokesperson said refusal to work is not punished through solitary confinement. But individuals can still be sent to solitary for things like apparent gang membership, risk of escape, or a history of violence. Four current or recently incarcerated individuals told the Observer stricter security levels like solitary are still imposed or threatened in what feels like retaliation for refusing to work. Some incarcerated Texans say they also face consequences if they report injuries.

From 1911 to the 1940s, the prison system was required to keep records on individual prisoner punishments, made logs on punishment available for public inspection, and described them in legislative reports.

On November 27, 1876, a guard at the Lake Jackson Plantation convict camp ordered Frank Furlow to be put in the stocks after finding his work unsatisfactory. A Black farm laborer from Palestine, Furlow stood on the balls of his feet for five minutes before being released. Unsatisfied, the guard ordered Furlow placed in the stocks again. A witness later reported to investigators that Furlow “jumped and flounced about to a considerable extent.” He was later “taken out and found to be dead.” Furlow was one year into a 10-year sentence for mule theft. He was 17.

Deaths from prison punishments led to limited reforms in 1910. But, for decades, legal disciplinary measures still resembled methods of torture used on former slaves, and some of the worst continued after convict leasing ended. One common form of punishment was whipping by “the bat,” a leather strap with a 1- to 3-foot wooden handle at the end. Legal punishments, including the use of those bats, whips, and solitary confinement in a dark cell were recorded along with the date, number of lashes, and the reason for punishments—often for refusal to work.

“Boss Band pushed me beyond any limits I dreamed I had.”

In the 1920s, Henry Tomlin’s prison records reveal that for refusing to work he was beaten, then shut in a dark cell at least five times, sometimes for up to an entire week. In his memoir, Tomlin said prison guards also cuffed his hands together and hung them from the ceiling, causing his legs and wrists to swing until he “gave out” and fell, only to be tied up again. Others testified to the 1910 legislative committee about “hanging in the window”—being chained by their wrists to the top of a barred window.

Another form of punishment, standing on a barrel or milk crate for a prolonged period, was used at least until the 1980s, according to an account in a book written by Albert Race Sample and corroborated by the Observer’s interviews with another formerly incarcerated man.

Sample, who was incarcerated at the Retrieve Unit in Brazoria County in the 1950s and 1960s, described a field boss with a reputation as a “traveling executioner,” who would allegedly shoot incarcerated people dead in the fields for no reason. “Boss Band pushed me beyond any limits I dreamed I had,” Sample wrote in his memoir Racehoss. “He gave no alternatives, it was do or die. At times I felt like throwing up both my hands and screaming ‘Kill me! Kill meeee!!’”

It would be 70 years after the end of convict leasing in Texas when some reforms promised during the Progressive Era would be realized, this time through the initiative of an incarcerated worker.

In 1972, David Ruiz, who served time at the Ramsey Unit in Rosharon, among other prisons, filed a lawsuit challenging the system’s unconstitutional treatment of laborers, including racial discrimination and unsafe working conditions. The suit, filed in 1972 in the U.S. district court in Tyler, accused the sprawling prison system of subjecting its wards to cruel and unusual punishment. At one point, in retaliation, Ruiz was sent to work in the fields with his leg in a cast, according to Perkinson’s book, Texas Tough.

U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice signed several orders in the late 1970s in an attempt to prevent TDCJ staff or other officials from retaliating against plaintiffs like Ruiz. In 1980, after the U.S. Department of Justice joined the class-action lawsuit and after more than 300 witnesses testified, Judge Justice determined that TDCJ conditions constituted cruel and unusual punishment. The following year, he approved a consent decree that, in part, addressed shortcomings in the system’s work safety standards.

But even Justice’s orders never required the level of disclosure about prison field work injuries and deaths formerly imposed by the Legislature in the aftermath of convict leasing. For a few years after the Ruiz ruling, the prison system faced more scrutiny, but other courts later weakened those reforms.

Kevin Bruno, whose great-grandparents were both enslaved in Texas, worked the fields at the Darrington Unit in the 1980s and said physical punishments remained common. He said when the guards called up a “hoe squad” to report to work at sunrise, the men would have to run down the hallway as fast as they could. “The last man always got kicked in the butt by the captain,” Bruno said. For minor infractions, like being late for work, prison fieldworkers were forced to stand on top of a wooden milk crate for hours—sometimes overnight. If you fell off, your time started over or you were beaten, he said. These crates would be in common spaces like hallways, so those being punished were on display.

“You’d be surprised how strenuous standing on a milk crate can be because, psychologically, you’re always thinking about maintaining your balance on this tiny crate and it just wears you down,” he said. Other times, he would be given a gallon of peanuts and told to shell them by hand. The process took hours, leaving his fingers raw and tender.

A TDCJ spokesperson denied that the milk crate punishment was ever used by the agency.

Bruno said fieldworkers were allowed to fight and attack one another almost with impunity, as long as the guard gave someone permission to briefly put down their hoe. “If you had a problem with somebody next to you, you couldn’t just start fighting,” Bruno said. “You had to ask permission. You would say ‘Trying to get me one here, boss,’ and the field boss would either tell you ‘Not right now’ or ‘Make it quick and get back to work.’” Several other formerly incarcerated farmworkers shared reports of violence in the field.

The cornfields in particular were tall and dense. “Inside the maize, there was always at least beatings,” Bruno said. He said killings were “frowned upon” because “if you killed them in the fields, that stopped work. They didn’t care about the guy dying; they cared about you stopping work.”

A TDCJ spokesperson confirmed that the agency does not publish reports about prisoner punishments and that the agency considers disciplinary proceedings, complaints, and grievances confidential in most cases. The spokesperson declined to comment on the differences between past and present reporting requirements and stated that TDCJ “does not allow fighting in its facilities or at any inmate work assignment.”

Jason Walker worked the fields in 1999 at the Roach Unit in a rural area west of Wichita Falls. Walker, who is Black, said he was forced to pick cotton there. Walker, who had done time in various TDCJ units, said that each unit has a distinct culture and set of operating procedures, but the fieldwork was equally abominable everywhere.

“It didn’t matter if prisoners were at ‘burnin’ hell’ [a nickname for Clemens] or Roach Unit,” Walker told the Observer. “Just as we all have to wear the same cheap white top and bottoms, prisoners felt the same wrath from the hoe squad ‘boss man’ anywhere forced farmwork—slave labor—was imposed. It was a statewide culture.”

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to include additional information from an autopsy report and about the role of TDCJ’s Office of the Inspector General.