Texas Is Seeking Trump’s Approval of its Planned Parenthood Ban. Will Other States Follow?

A win for Texas could greenlight other states to kick the women's health provider out of Medicaid programs.

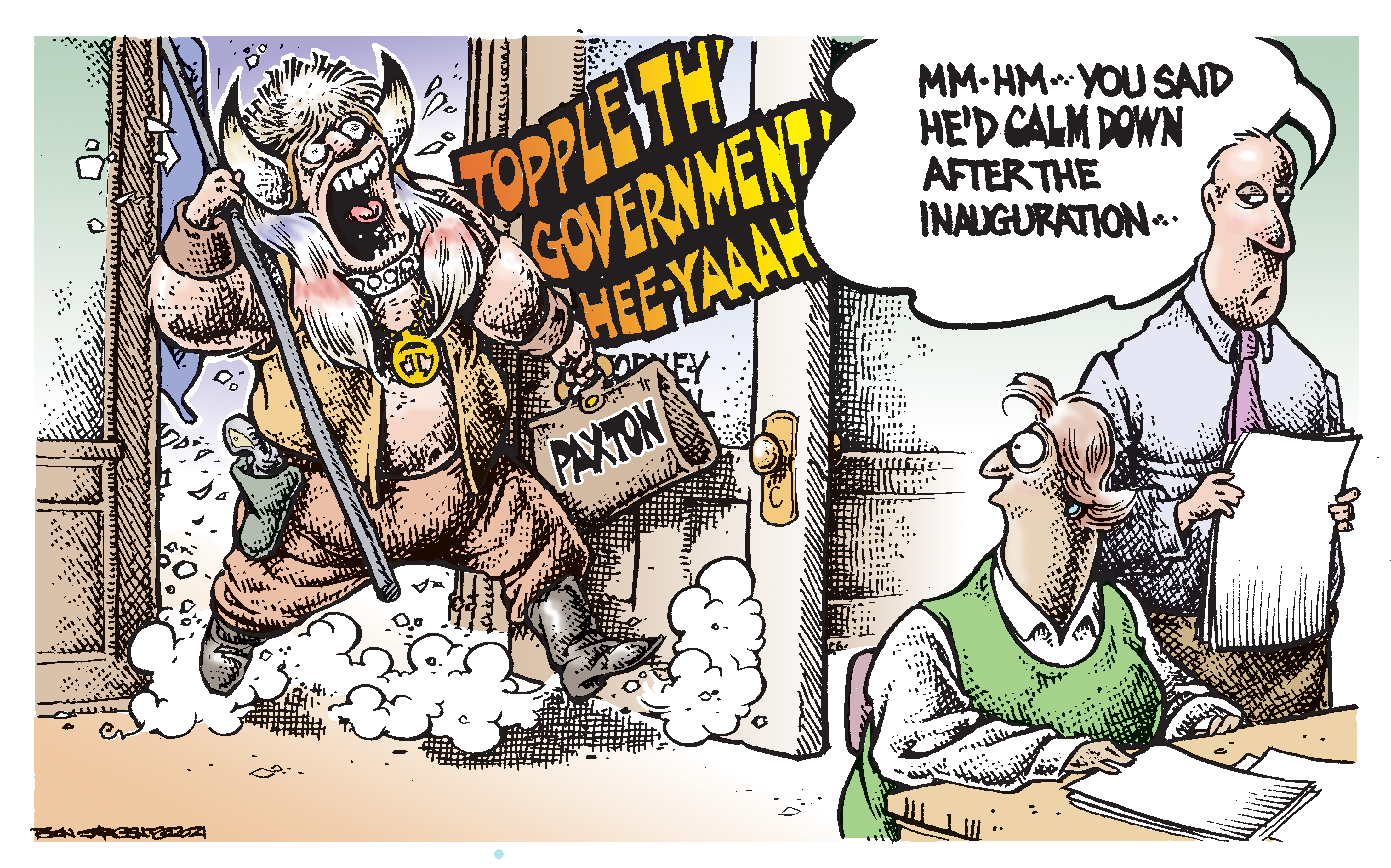

Texas is testing the Trump administration’s antagonism toward Planned Parenthood with a controversial move that could set a path for other states to defund the nation’s leading reproductive health provider.

Four years ago, Texas’ vendetta against Planned Parenthood led the state to forgo millions of dollars in federal funding in order to strike the provider from its low-income women’s health program. Hoping it now has an ally in the new administration in Washington, the state is asking Trump whether it can now receive that money, without restoring access to Planned Parenthood.

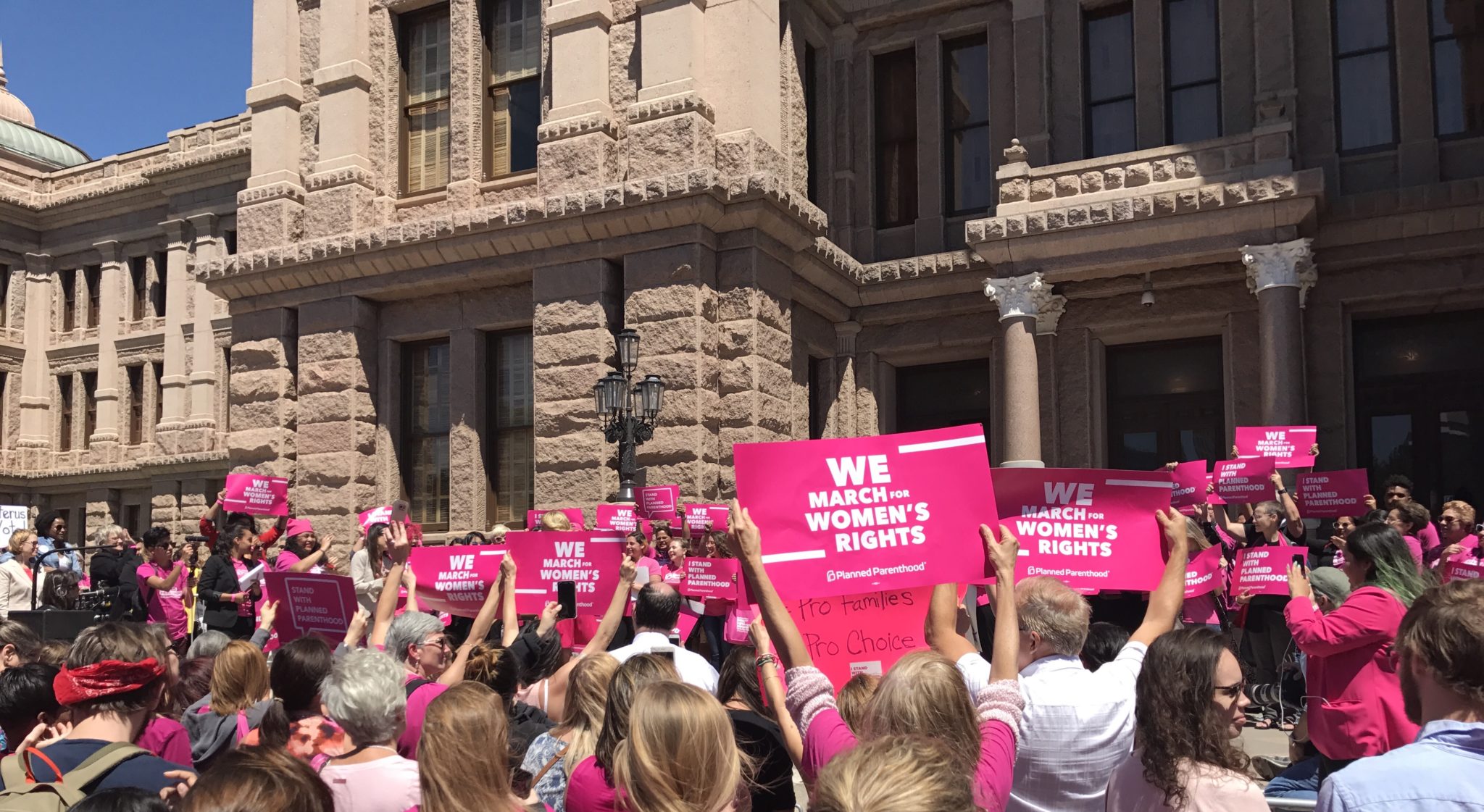

It’s an unprecedented move that women’s health advocates worry could inspire other states to slash funding from Planned Parenthood with impunity.

“The concern if the federal government grants this waiver is other states could make the same bad decision Texas did — to try to serve as many women but exclude what’s often the largest and most efficient provider available,” said Stacey Pogue, a senior policy analyst at the left-leaning Center for Public Policy Priorities.

Texas is seeking Medicaid funding over five years to largely cover the cost of its state-funded Healthy Texas Women Program, according to a waiver request presented by state health officials at a public hearing in Austin on Monday. In 2019, the first year, the state is asking the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to cover about $56 million of the $71 million total.

It’s not the first time Texas is asking the federal government to fund a women’s health program that bans Planned Parenthood, but it could be the first successful attempt. President Donald Trump signed legislation last month to bar federal funding for the organization, and the Republican health bill that recently passed the U.S. House includes major cuts to Planned Parenthood.

When the Obama administration rejected Texas’ effort to kick Planned Parenthood off the Medicaid Women’s Health Program, the state pulled out and created its own state-funded program, now called Healthy Texas Women, in 2013. The program covers breast and cervical cancer screenings, contraception, immunizations and other services for low-income women ages 15-44 who are not eligible for full Medicaid benefits, but excludes any abortion providers or their affiliates.

Taxpayer dollars are already prohibited from funding elective abortions; the state’s decision cut Planned Parenthood’s family planning services, cancer screenings and other care.

Supporters of the Medicaid waiver request say it will bring federal family planning dollars back to the state, free up general revenue funds in a tight budget year and increase access to health services for low-income women.

But Planned Parenthood advocates say the state program does not fill the gap created by the provider’s exclusion. If the federal government approves the waiver, it would put its stamp of approval on a program that has decreased access to care for political reasons, they say.

“The federal government would be rewarding bad behavior, because the state has not been doing a good job in making sure women who need these services are actually receiving care,” said Yvonne Gutierrez, executive director of Planned Parenthood Texas Votes. She noted this has been a constant concern since the Texas Legislature slashed family planning funding in 2011, forcing 82 family planning clinics to close.

Planned Parenthood had previously served more than 40 percent of the women enrolled in the Medicaid Women’s Health Program in Texas.

Data released by the state show a significant decline in women accessing services under the state-run program. The number of clients served dropped from nearly 104,000 in the Medicaid program in 2012 — before the state took over — to about 70,000 in Texas’ program in 2016. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year found that following Planned Parenthood’s exclusion, contraceptive use declined and Medicaid births increased in areas served by its clinics.

“The state has struggled for years to try to build a provider network that could replace Planned Parenthood and still four years out hasn’t done that,” said Pogue, the policy analyst.

Meanwhile, a court has temporarily blocked Texas’ recent attempt to ban Planned Parenthood from all Medicaid coverage, but advocates say this waiver decision could impact how the case proceeds, and spur further litigation. Several other red states have made similar attempts to exclude Planned Parenthood, but have not gotten as far as Texas.

Leslie French, associate commissioner for women’s health services, said Monday that the state has not yet done a thorough analysis of the data to explain the lower client numbers.

The state will file the waiver application with the federal government at the end of June.