‘Last Sheriff in Texas’ Tells True Story of State’s Deadliest Lawman

James P. McCollom’s "The Last Sheriff in Texas" paints the South Texas town of Beeville as a microcosm of Texas politics and policing — past, present and future.

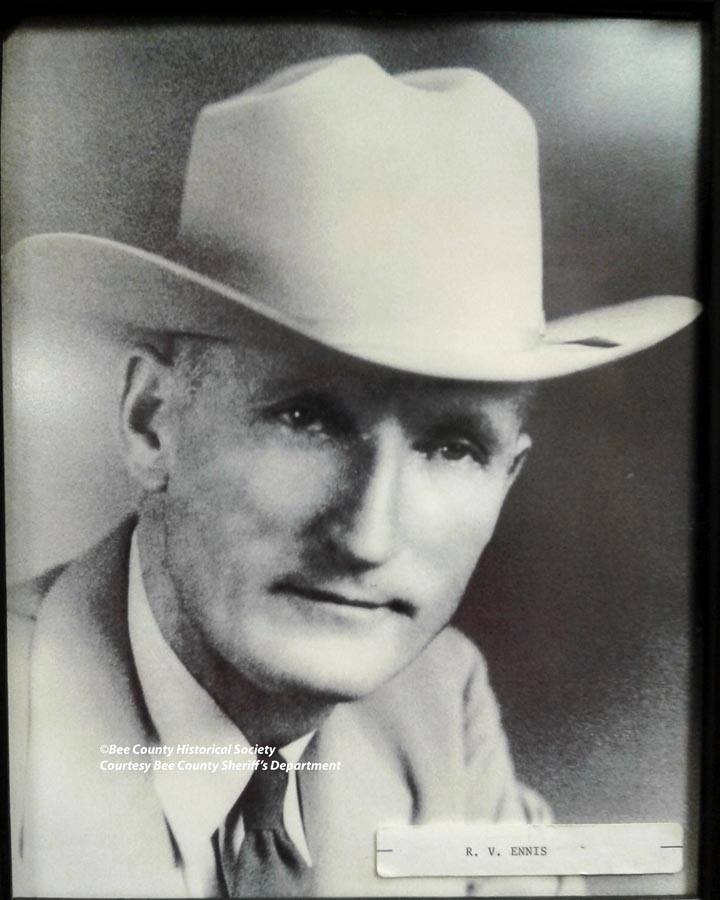

It begins with a firefight. In a quiet patch of South Texas in 1947, the sheriff has unloaded his six-shooter on a pair of criminals. In the process, he’s taken a handful of rounds to the torso. The town of Beeville gathers outside the hospital, waiting for the news that Vail Ennis has, somehow, survived. The titular sheriff in James P. McCollom’s The Last Sheriff in Texas: A True Tale of Violence and the Vote, Ennis is a kind of hyper-violent, unbound lawman presumed to typify the Old West. But carefully, thoughtfully and with an abundance of energy and charm, McCollom tells of a man who was one of a kind, a folktale come to life, and along with him, all the trouble that accompanies setting a folk hero loose in a small town.

The Last Sheriff is a true story, intensely researched, passionately written and dense with meaning, both for its examination of our history and its tacit meditation on what that means today, when police brutality and accountable democracy are ever-present concerns. It’s a big story full of visceral details and driven by real-world characters. The writing is rich and fulfilling, packed with detail and Easter eggs of Texas history and culture. Sometimes the tone borders on rhapsodic, but it seldom delves into anything patently reverential. McCollom and his subjects have a niggling awareness that things are rarely simple.

Vail Ennis killed seven men during his career, an unmatched record for Texas lawmen. After the gun battle that bracingly opens the book, and a subsequent mention in TIME magazine that brought it into the national consciousness, everything in Beeville begins to unravel just a bit. We see these changes through the eyes of an idealistic young man named John N. Barnhart, a childhood declamation champion and a stand-in, perhaps, for the author, who also grew up in Beeville.

Barnhart was a wide-eyed University of Texas at Austin student, then novice attorney, then freshman state representative, an optimist and liberal-leaning moderate in the McCarthy era. The story sets him adrift in a volatile sea of uniformed Aggies and aging ranchers who are chiefly concerned with law, order and commies. Eventually, Barnhart is forced to make a choice: whether to tolerate the lionized but dangerous Ennis, or to stand against him and face the uncertainty of a new order.

A True Tale of Violence and the Vote

by James P. McCollom

COUNTERPOINT PRESS

$26; 272 pages

Ennis was a violent man who believed he was protecting the weak. In one scene, he beats a man harassing a waitress to a bloody pulp when the harasser resists arrest. A small-eyed, thin-lipped, Stetson-wearing knight guarding his domain with seeming impunity, he runs his mouth nearly as fast as he runs his trademark steed, a green Hudson Hornet, down the dirt roads of his South Texas fiefdom. His driving habit accounted for a manslaughter, his trigger finger for more deaths than can be counted on one hand. And still, Ennis is re-elected, again and again, even as the city fathers cluck their tongues, whisper the word “violence” with sad resignation and fund a series of inept candidates. The perennial coming-to-terms with Ennis, through elections, serves largely as the book’s central plot. Ennis is a figure worth considering today, and McCollom contextualizes him so fully that a reader could scarcely pick up a paper without seeing his shadow.

The prose is emotional and slightly idiosyncratic, sometimes verging on verse, sometimes wrapped in vernacular. McCollom renders every scene in cinematic detail. So much detail, in fact, that many of the book’s establishing shots — florid descriptions of Beeville or Pettus or Austin on a given day — can begin to feel redundant, especially when we’re watching the subjects cycle back to vital but familiar rituals of elections, rodeos and daily banter at the cafe, country club or beer joint.

McCollom renders every scene in cinematic detail. So much detail, in fact, that many of the book’s establishing shots — florid descriptions of Beeville or Pettus or Austin — can begin to feel redundant.

The detail McCollom achieves, however, is far more of a feature than a bug. The reader feels the gnawing tensions that bubble under the surface and eventually explode, particularly as Johnny Barnhart, who is the point-of-view subject, begins to see the fault lines running beneath the town. The Cold War is sinking into the American psyche. The state of Texas, once wild and wooly, is now mostly urban. The cattle trails are empty, and cowboys lope to and from the bar, where they keep telling stories of youthful prowess, of skills that matter little to Camp Ezell, John Barnhart, Russ Wade and the other men with modern jobs. Yet those same city folk cling to the notion that these cowboys are special, that they are what makes the place special.

The world was surely new, “Yet small ranchers patiently waited for things to go back to normal. You could still drive out any county road and little old ranch houses with wooden corrals, a barn, and chicken yard. The road from Beeville through Cadiz to Oakville led past dozens of such places like Roman ruins with the Romans still living in them,” McCollom writes.

McCollom, like the real people he renders on the page, is entrenched in Texana, the folkloric elements that give a Texas twinge to a universal story of ballots and bullets. There is the Alamo and its defenders, and old cowboys in the rodeo parade flying flags of a not-yet-forgotten way of life. There are six-shooters, shootouts, ranchers, oilmen, J. Frank Dobie, LBJ, Texas Rangers, the Aggie War Hymn and a state capitol perfumed with cigar smoke. All of it coalesces into a beautifully rendered portrait of a changing nation.

In some ways, The Last Sheriff reads like a kind of prequel to Billy Lee Brammer’s phenomenal entry to the Texas canon, The Gay Place. In both books, an increasingly urbanized, cosmopolitan Texas struggles with the tension between modernity and tradition. As a story about violence, policing, elections and society, McCollom’s book is immediate. As a reflection on Texan myth and reality, it is timeless. Lonesome Dove it’s not, but in many ways it gives T.R. Fehrenbach, author of Lone Star: A History of Texas and Texans, a run for his money in encapsulating the Texan mindset. McCollom has earned his place in the canon with a tale that’s part true-crime, part sociological nonfiction, and part national epic.