At Texas State, Student Activists Make Their Voices Heard

The last year has seen a rash of hate incidents, protests and clashes both in the San Marcos community and at Texas State University.

On November 15 — one week after Election Day — someone posted a flier on a bathroom wall during the morning coffee rush at the Root Cellar Bakery in San Marcos. Plastered with images of hooded Ku Klux Klan members waving the Confederate flag, as well as portraits of Donald Trump, Arnold Schwarzenegger and a posse of armed white men, the flier read, “White men rule. Always have, always will,” and “Hallelujah! America will be white again.”

It was a strange and disturbing incident for the trendy bakery, which overlooks the town square. But then again, a lot of strange things have been happening in San Marcos.

The sleepy Central Texas college town of 60,000 is better known for the gin-clear waters of the San Marcos River than for political activism. Nearby Austin tends to get all the credit for that. Yet the last year has seen a rash of hate incidents, protests and clashes both in the San Marcos community and at Texas State University — and tensions have only risen since Trump was elected.

Bill Cunningham, a former chair of the Texas State University System Board of Regents, has lived in San Marcos since 1977, and attended Texas State during the Vietnam War, when he lost his job as editor of the campus newspaper after taking a stand for anti-war protesters. “I’ve seen lulls in student activism over the years, but what I’m seeing right now is a lot more students who are really concerned about their future, who are getting very active,” he said.

Like countless other Texas towns, San Marcos still bears the fingerprints of its racist history. A downtown plaque honors the mayor who hosted KKK Day in his nearby movie theater, and Ed J. L. Green Drive, a verdant stretch of road adjacent to iconic Spring Lake, is named for a Klansman who was also county clerk. Longtime local newsman Walter Buckner, whose family operated the San Marcos Daily Record until 1975, wrote a few years later in his memoir, “Not everybody will admit to having been a member of the Ku Klux Klan. I was. I had my hood and my robe, and I was proud. … I make no apology now for my membership and activity, however insignificant.”

It’s against that backdrop that San Marcos is changing. It’s one of the fastest-growing cities in the nation, ballooning by 35 percent from 2010 to 2015. Texas State University is changing, too. For the first time in the school’s 117-year history, whites comprise less than half of the student body. Hispanic and African-American students represent 35 percent and 11 percent of the campus population, respectively.

University administrators say they’re proud of the growing diversity. “We have a very high retention rate of Anglo students, but it is not as high as it is for Hispanic students, which is not as high as it is for African-American students — which is unheard of,” Brian McCall, Texas State University System chancellor, told the Texas Tribune in 2014.

Those numbers belie what students like Russell Boyd, a junior public administration major and homecoming court nominee, describe as an unwelcoming campus climate. “A lot of people are questioning if they made the right decision coming here,” said Boyd, who is black. “Many of us are questioning that every day, and some are even advising others not to come, because it is not the school it claims to be.”

Boyd said that the university should hire more faculty of color — only 3.5 percent of Texas State professors are African American and 10.8 percent are Hispanic — and require cultural competency courses for all faculty. His fellow student activists have also called for the creation of black and Latino studies programs, both of which are in the works, as well as for university president Denise Trauth to endorse Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA).

History professor Dwight Watson said the university should do more to recruit and retain faculty of color.

“Transformation does not happen in a vacuum,” Watson said. “[Administrators] cannot say we will have more minority faculty if they don’t aggressively and actively recruit them and create an environment conducive to their development.”

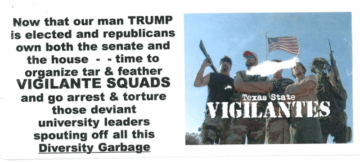

A handful of fliers posted on the campus on November 9 called for the “torture” of “university leaders spouting off all this diversity garbage.” On November 12, Texas State student and drag performer Alejandro Camina was assaulted by a man who Camina said attacked him for wearing heels.

Diann McCabe, director of academic development for the Honors College, attended Texas State during the Vietnam War, when in 1969 administrators expelled 10 of her classmates for protesting the conflict.

McCabe says that campus activism has risen in the past year, citing a march in July 2016 against police violence. Organized by Black Lives Movement, a student organization that Boyd co-founded, the march drew several hundred San Martians — students, community members, clergy, faculty, City Council members — for speeches on the steps of the historic county courthouse.

“The gathering at the church and the subsequent march to the courthouse was unusual — taking the campus into the community,” McCabe said.

The march was just the beginning. In September, campus officials quietly removed an 85-year-old monument to Confederate president Jefferson Davis. The next day, coat-tailing the movement started by NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, Black Lives Movement persuaded nearly 150 students to sit during the national anthem at Texas State’s first home football game — a sea of mostly black fists thrust skyward.

Texas State officials haven’t ignored students’ calls for more resources. The Honors College is set to open a multicultural lounge this spring. Last year, the campus hosted a talk by Black Lives Matter co-founder Opal Tometi, and activist Angela Davis is scheduled to visit in March.

But these progressive strides haven’t pleased everyone. In addition to the racist flier at Root Cellar Bakery, a handful of fliers posted on the campus on November 9 called for the “torture” of “university leaders spouting off all this diversity garbage.” And on November 12, Texas State student and drag performer Alejandro Camina was assaulted by a man who Camina said attacked him for wearing heels.

Two days later, the body of Travis Green, a prominent student leader, was discovered in a campus stairwell. To halt rumors that Green, who was gay and black, had been murdered, Trauth took the uncommon step of issuing a statement to clarify that Green took his own life.

On November 9, at least one conservative activist paraded around campus with signs pushing for a border wall, and in December hateful fliers emerged again, this time urging the reporting of undocumented students to immigration authorities. Citing safety concerns, the Muslim Students Association canceled all remaining activities for the fall semester.

In addition to multiple meetings with students, Trauth published a letter to students on the school’s website, writing, “I have an absolute duty to publicly speak out as an advocate on issues that directly impact the university and our academic mission.”

Yet Trauth is the only president among those at the seven largest universities in the state designated as Hispanic-serving institutions who declines to “publicly speak out” in favor of DACA. More than 600 university leaders nationwide, including University of Texas System Chancellor William McRaven, have signed an open letter in support of DACA expansion for otherwise undocumented students.

Texas State spokesperson Matt Flores told the Observer, “President Trauth has not signed the DACA statement. She has been meeting with campus groups for several weeks — and will continue to do so in the spring — to listen to concerns and strengthen lines of communication with the university community.”

Cunningham, the longtime San Marcos resident who also chaired the Board of Regents for the Texas State University System, said of Trauth, “She is in a sticky situation; she’s very sympathetic to students, but she answers to an all-Republican-appointed Board of Regents, and her funding for the college comes from a Republican-dominated Legislature, and the governor has made very clear that he wants no sanctuary [for undocumented immigrants] anywhere.”

“It’s sometimes easy to get discouraged in times like these, but faculty members have made their support clear and students are ready.”

Tensions ratcheted up even more in late December with news that the university’s official dance team, the Texas State Strutters, would perform in Donald Trump’s inaugural parade in Washington, D.C.

Widespread outcry led the Strutters to shutter their Twitter account and delete critical comments on their Facebook page. Black Lives Movement also started a petition demanding that the team drop out of the parade.

I spoke to two former Strutters, both of whom asked to not be identified, given the team’s intense culture of loyalty and conservatism. Although the dance team was whites-only when it was founded in 1960, the Strutters’ ethnic composition has, like that of Texas State, evolved.

One former Strutter, who is Latina, said she was disappointed but not shocked by the team’s decision. “The organization has many members who are women of color, and my heart breaks for them,” she said.

Another former Strutter said, “Like it or not, it’s a political statement that [shows] support for Trump, who has degraded women and minorities unapologetically.”

The performance took place as planned, but campus activists remain resolute on ushering in progressive change at Texas State.

Root Cellar Bakery, the cafe targeted with the Klan flyer in November, has begun hosting a monthly series of social justice happy hours organized by professors and aimed at uniting activists in the campus and the San Marcos community.

Tafari Robertson, a public relations junior who leads the Pan African Action Committee at Texas State, attended the January 18 event.

“It’s sometimes easy to get discouraged in times like these, but faculty members have made their support clear and students are ready,” Robertson said. “We’re all working hard to make sure our voices are heard. There’s a lot of work to do, but it’s nice to finally see some results and to know the administration is listening, one way or another.”