We Are Writers, Too

I enrolled at Texas State hoping to find my voice as a Chicana writer. Instead, I was told to whitewash my work.

Like many other MFA programs, Texas State University’s creative writing program is too white, too heterosexual and too male. There is not a single Mexican-American, Chicanx, Tejanx, Native-American or even Latinx professor on staff. In the 2014 visiting writers series, all were white, and of 10 writers on the 2015 program, seven were white — until last week, when they replaced a white visiting writer with the 2016 Poet Laureate of Texas, Laurie Ann Guerrero.

I noticed because I am a Chicana writer who graduated from Texas State with an MFA in fiction in May 2015, after spending three years trying to carve out a space for myself at a school that still privileges one kind of voice — educated, male, white — over all others.

At the end of my second year, I questioned the program director about the all-white visiting writers’ list. He told me: “I don’t see color, I only see writers.”

If only the director had seen color, he might have ended up with a program that reflects the richness and diversity of Texas instead of obfuscating and excluding the experiences of writers of color.

In 2011, I decided to pursue my MFA after I published a childhood memoir back in 2008. I was searching for a writing program that would help me — a first-generation college student — become a well-rounded writer and experienced teacher. I applied confidently, mostly motivated by the dream that I’d finally be accepted into an academic writers’ community.

I should have known better. In the first year, some of my white peers told me that my use of Spanish in my stories alienated them. My Mexican characters, they said, were too stereotypical and not quite believable. Yet when white students wrote about a culture other than their own, they were praised for their efforts — echoing the way non-native Spanish speakers like Ernest Hemingway and Cormac McCarthy have been praised for their use of the language. Convinced I needed to take these comments into consideration, I began to minimize and italicize the Spanish in my writing.

I still couldn’t believe it when the program director told me Chicano Realism — a style that incorporates fantastical or mythical elements into realistic fiction focused on Chicanx narratives — isn’t “academic.”

And yet somehow I still couldn’t believe it when the program director told me Chicano Realism — a style that incorporates fantastical or mythical elements into realistic fiction focused on Chicanx narratives — isn’t “academic.” The director lumped in my work with Gloria E. Anzaldúa and Richard Rodriguez, two completely different Mexican-American writers with dissimilar perspectives on identity and writing styles. The comparison, of Anzaldúa and Rodriguez to each other and then to my work, was intellectually inappropriate, not to mention baffling. Are Verne, Flaubert, and de Beauvoir all similar writers because they are all French?

But maybe Anzaldúa and Rodriguez were the only Chicanx writers the program director recognized. I know I don’t write like them. I do, of course, write about identity — I continuously find myself defending it in all aspects of my life, and writing at Texas State was no different.

I couldn’t escape the constant reminder that I had been marked by my own institution, and my own peers, as “other.” At an MFA bar gathering that still lingers in my memory, a white male student nonchalantly mentioned to a Chicana peer that he thought writers should be selected on merit, so it shouldn’t matter if the faculty was all white.

I found myself exhausted by these off-putting feints toward color-blindness, which are all too common in the writing industry. The 2014 VIDA count — which tracks gender inequality in top-tier publications — not only (re)confirmed the gender disparity within the industry, but also took race into its analysis, revealing an even greater gap. As a woman of color, I fight on both fronts — race and gender. To suggest that whiteness, uniquely, succeeds on merit is to suggest, not at all subtly, that writers of color are fundamentally less talented, less qualified, less-than.

I finally addressed my frustrations in my last workshop. We sat in the traditional circle and introduced ourselves. When it came to my turn, I unapologetically asked readers to refrain from critiquing the Spanish in my writing. That introduction turned into a red-faced Chicana rant, which I later channeled into a final essay that I hoped the faculty couldn’t ignore.

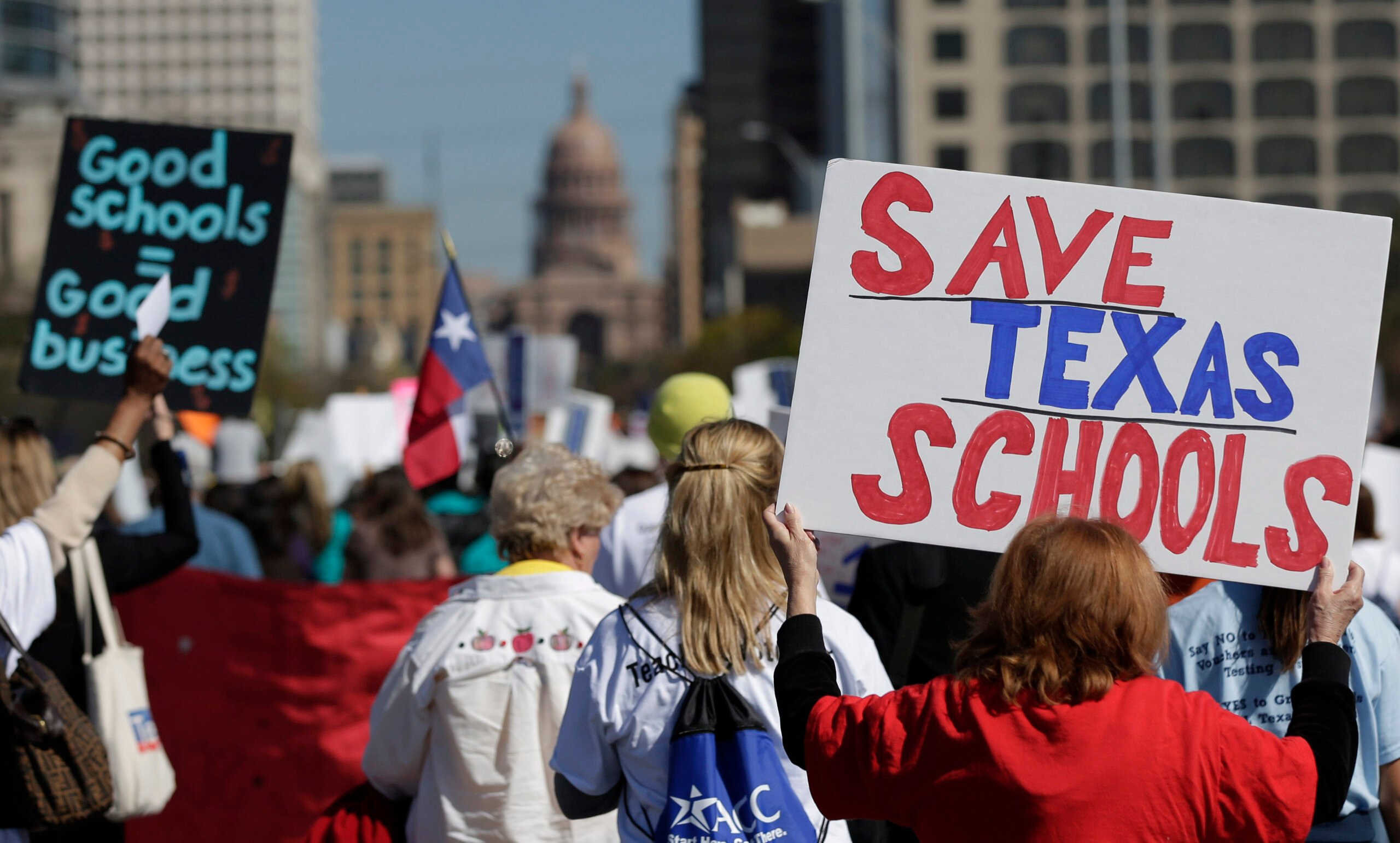

A month before graduating, I met with everyone I could — even the university president — to speak about the lack of diversity in the MFA program. It was all a bureaucratic hassle, with everyone from my thesis advisor to the heads of the department of English to the university vice president bumping me around from office to office and back again. Finally, I was shoved off to a new incoming MFA writing program director who said he’d take my feedback into consideration when addressing issues with current students.

That was ten months ago. I never heard from any of them, but I know the same problems still persist. I hear it from my new community of women writers of color from the school, with whom I’m helping to build a new creative alliance of resistance.

We first met, appropriately enough, at the only independent bookstore in Austin focused on Chicanx, Latinx and Native American literature: Resistencia Bookstore. We met next to a mural depicting an indigenous warrior posed under a brick wall, a pierced heart and handcuffs, symbolizing colonization, cultural oppression, and incarceration.

Three of us, current and former students, came to share our experiences, away from the frustrations and heartbreak we’d been through.

Together, we searched for literature that gives space for racialized communities of women who have been silenced by the color-blind whiteness of academia, of the mainstream publishing industry, of America itself. Resistencia is filled with bold names like Castillo, Silko, Erdrich, Butler and Davis.

We picked up A House of My Own, Sandra Cisneros’ latest book. Someone remembered that Texas State recently acquired her literary archives, yet none of us had read her while in the MFA program. On the next shelf, we found a collection by poet Laurie Ann Guerrero, a Tejana who lives just 50 miles south of San Marcos. While getting my Texas State MFA, I never heard her name mingled with Hemingway and Munro and O’Brien until I organized an event that brought her to the university’s Wittliff Collections in fall 2014, specifically to counter the all-white visiting writers’ list.

Slowly, I’m beginning to decolonize my writing. I no longer feel I need to italicize my Spanish, justify my history or pander to white readers who have so often seen me as an affirmative action case who shouldn’t be seen or heard.

Hell, I still catch myself revising for workshop, doubting my use of Spanish when I get rejected and judging where to submit based on the ethnicity of the editor. But slowly, I’m beginning to decolonize my writing. I no longer feel I need to italicize my Spanish, justify my history or pander to white readers who have so often seen me as an affirmative action case who shouldn’t be seen or heard.

At Texas State, things are changing, but slowly — too slowly. Recently, the program hosted two “diversity” talks for MFA students, yet attendance at these these events is optional for faculty and students. With the addition of Matthew Salesses’ visit earlier this month and the recent addition of Laurie Ann Guerrero to the visiting writers’ events, the program has made strides by inviting additional writers of color for a few special occasions. But I won’t be convinced of the university’s commitment to diversity until it is ingrained in the everyday makeup of the MFA program’s faculty and curriculum, rather than in occasional, and optional, conversations outside the classroom.

As for me, I know now, el español es parte de mi cultura, and my writing is, too. One day my name will be in places far beyond that MFA program. Today, I enter a new space to unite with a familiar community, to remind everyone who will listen, and myself: We are writers, too.

[Featured image of Texas State campus: Rain0975/Flickr/Creative Commons]