Texas Strikes Deal to Build Abbott’s Border Wall on Big Donor’s Ranch

The governor’s slow-moving wall scheme gets a major boost from a political ally as the state secures five miles of land for fencing.

More than a year and a half since Governor Greg Abbott launched his taxpayer-financed plan to build a border wall along the Texas-Mexico border, the state has made little progress. But Abbott may soon have several miles of new wall to tout—thanks to a major deal the state just struck with one of the governor’s top campaign donors.

Late last month, Texas acquired five miles of land to build 30-foot steel fencing through a sprawling 40,000-acre private ranch owned by Stuart Stedman, a Houston-based heir to an oil and ranching fortune who also happens to rank among the governor’s biggest political patrons.

Stedman has contributed $1.1 million to Abbott’s campaigns since 2015, including $600,000 in the most recent election cycle, campaign finance records show. In 2021, Abbott appointed Stedman to the board of regents of the University of Texas System, the type of influential post the governor has long used to reward his most generous political backers. Prior, Stedman was one of the governor’s appointees to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

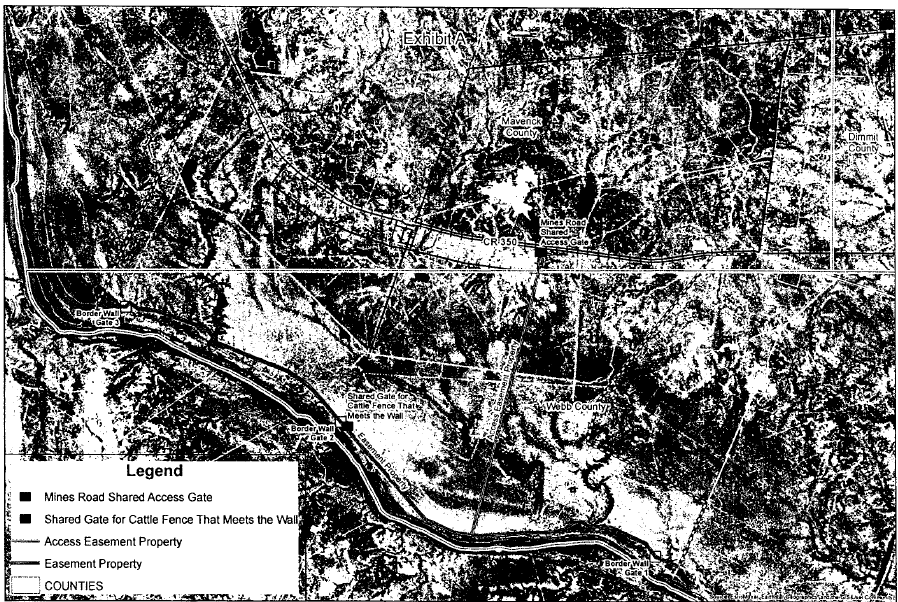

The Texas Facilities Commission (TFC)—the state agency charged with orchestrating Abbott’s wall project—inked the agreement with Stedman to build through a property he owns called Faith Ranch in northwestern Webb County, according to a copy of the easement the Webb County Clerk’s Office posted earlier this week. TFC paid Faith Ranch $1.5 million to acquire permanent land rights for the wall, per state agency expenditures compiled by the Comptroller’s Office.

The deal marks the state’s largest and most costly land acquisition so far for the Texas border wall program, providing a shot in the arm for the governor’s pet project. Since launching, Abbott’s wall-building crusade has been hampered by delays; only 1.6 miles of new fencing has been completed on a remote piece of state-owned land in the Rio Grande Valley.

The Stedman transaction is also the first sign of where the state intends to begin building a wall in the Laredo region, which has quickly become the focal point of construction plans—despite a long history of opposition in the area. Already this year, TFC awarded construction contracts to two firms worth over $350 million to build 16 miles of wall in Webb and neighboring Zapata County.

These contracts have drawn outrage from a local coalition of border wall opponents who, after fending off Trump’s wall plans, are now scrambling to inform and organize landowners and border communities in an effort to block the state’s plans. Unlike Trump’s wall scheme, which relied on federal eminent domain powers, Abbott’s wall depends on cooperative landowners, with whom the state is haggling.

The Faith Ranch deal between the state and a wealthy ally of the governor, opponents say, shows that Abbott’s wall is all about politics.

“They sure keep it all in the family, don’t they?” said Tricia Cortez, a Laredo-based organizer with the No Border Wall Coalition. “It’s incredibly disappointing that a landowner [who lives in Houston] is going to allow the governor, for purely political reasons, to impact our only source of drinking water and do so much harm to the land for such an obscene amount of taxpayer money.”

“It’s incredibly disappointing that a landowner is going to allow the governor, for purely political reasons, to impact our only source of drinking water and do so much harm to the land for such an obscene amount of taxpayer money.”

The state’s dealings with a close political ally of Abbott on a taxpayer-funded project, which is also one of the governor’s top political priorities, smacks of potential ethical conflicts. For instance, did Stedman give the state a steep discount to buy his land (effectively amounting to an in-kind donation), or did the state pay above market value for the ranch property? (TFC does appraisals of the land it’s buying, but the agency is not releasing those records.) Further, is the state building a costly wall there because of convenience rather than actual security considerations?

“There’s an obvious conflict of interest when you mingle public and private money,” said Brandon Rottinghaus, a political science professor at the University of Houston. “There are all kinds of problems that result. Then when you throw in a dash of politics, it makes it even more unsavory.”

The Governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment from the Texas Observer, nor did Stuart Stedman. TFC said the governor had no involvement in the Faith Ranch deal. While TFC commissioners (all Abbott appointees) have referenced their direct engagement with landowners on the border wall project in past meetings, the agency would not comment on whether any were involved in this deal. Agency staff, as well as its contracted project managers and land agents, could also have handled it alone.

TFC has repeatedly refused to provide details about where exactly the state intends to build its new barriers, citing security concerns and ongoing negotiations with landowners. The agency similarly declined to confirm its Faith Ranch plans or the $1.5 million purchase price—facts that were revealed in the Webb County easement filing and comptroller expenditures data. “Due to security concerns and protecting procurement integrity, we are unable to confirm these data points,” TFC spokesperson Francoise Luca said in a statement.

One of the two Laredo-area state contracts—awarded in January to the Trump-allied wall builder Fisher Sand & Gravel—states the first phase of construction will begin on private land “northwest” of Laredo. Other TFC documents detail the state’s proposed wall alignments, which include a five-mile route through Faith Ranch.

The Fisher contract will cost the state an average of $24 million per mile of wall; at that rate, the Faith Ranch segment would cost about $120 million. The easement states that the wall, designed to the same specifications as Trump’s federal wall, will be constructed out of 30-foot steel bollards with at least 6 feet of concrete foundation below ground, along with lighting, surveillance cameras, and roads on each side of the fence.

The state’s border wall will replace an existing “deer-proof high fence” that currently runs the length of the ranch along the river, according to the easement.

In all, Texas has awarded about $850 million in “design-build” contracts to build over 40 miles of wall in Cameron, Starr, Val Verde, and Webb Counties. Construction began late last year on a roughly one-mile segment of land in rural Cameron County, and Abbott visited the site to hold a press conference last month. TFC officials said at a meeting last week that contractors are finally expected to begin construction on several border wall sites in the coming weeks.

That could include Faith Ranch, where the state appears to be rushing to begin construction. Daniel Perales, a former Border Patrol agent in Laredo, told the Observer that he’s heard firsthand from retired border agents and police officers who are being recruited to provide armed security services on the ranch’s construction site.

Perales, who is now an avid birder and president of the local Audubon Society, is a conservative Trump supporter but strongly opposes building a wall in Webb County, a populous border county essentially untouched by past federal wall-building. “It doesn’t make sense,” he said. “It’s very invasive” to the region’s riparian ecosystem, which relies on the Rio Grande.

As Cortez explained, the wall route in Faith Ranch is “out in the middle of nowhere, and it’s filled with very tall bluffs and arroyos,” which means it doesn’t have the same border security needs as other areas in the region. “Why the state or the governor wants to blow so much money that we need on real solutions and other real problems is mystifying.”

Meanwhile, farther downriver, state land agents have been making offers to owners with land along other targeted routes in Webb County. Cortez and the No Border Wall Coalition have recently hosted town halls to inform local residents about Texas’ border wall plans and to warn them not to sign anything–“¡No firmen nada!”

Organizers fear that some residents may take the state’s offer, believing incorrectly that the state can take their land either way.

“Property owners have the power,” Cortez told residents at one of the February town halls in the tiny town of El Cenizo. “The government cannot build it if you do not sign it.”