Texas’ Maternal Mortality Rate: Worst in Developed World, Shrugged off by Lawmakers

Lawmakers largely ignored the state's pregnancy-related death rate that doubled over a two-year period.

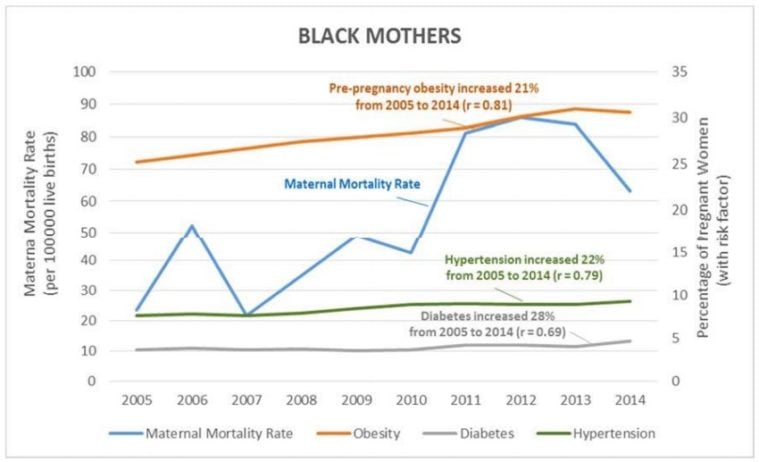

When she got pregnant four years ago, Representative Shawn Thierry knew she was at risk. She was 42 at the time, an age at which women are more likely to face pregnancy complications. “But I certainly didn’t know that I was three times more likely to die by virtue of being African-American,” she said, referencing a disturbing trend revealed in a state report last year.

Thierry nearly died in childbirth. In May, she shared her story for the first time in public at a briefing on reproductive justice for black women. Thierry said she had a severe reaction to a routine epidural. Her heart started racing and she couldn’t breathe. Doctors had to perform an emergency C-section. She and her daughter are healthy but Thierry, a first-term Democrat from Houston, told the audience that she’s lucky to have had access to high-quality medical care that saved her life. “I would have been one of those statistics,” she said.

Three years later, in 2016, Thierry read with interest a report by a state maternal mortality task force that found that African-American women in Texas are much more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes in the year after birth than white or Hispanic women. That report came on the heels of research showing that Texas’ maternal mortality rate had doubled over a two-year period, and now exceeds that of anywhere else in the developed world.

In the 2017 legislative session, Thierry’s No. 1 priority was legislation requiring more research into why so many new African-American mothers in Texas are dying. But despite bipartisan support, the measure was indiscriminately killed by the far-right House Freedom Caucus last month as part of what came to be known as the “Mother’s Day Massacre.”

Despite what appears to be an alarming crisis, lawmakers set only modest goals for the session. Most legislation focused on extending research efforts, rather than addressing what the maternal mortality task force has said is the underlying problem: lack of access to health care. Even the calls for more research languished during a legislative session in which trans people’s bathroom use was a top priority. In the end, only two piecemeal bills dealing with maternal mortality passed.

Legislators failed to even extend the task force itself; it’s now set to expire in September 2019. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick killed legislation that would’ve continued the research group through 2023 in order to try to force a special session over the so-called bathroom bill and property tax reform. (The task force bill was caught up in a last-minute standoff between the House and Senate. The House added an amendment that would have avoided a special session by continuing critical agencies, including the Texas Medical Board. Patrick balked and the bill never came up for a final vote.)

“Women’s health once again got caught in the political crossfire,” said Thierry.

A bill authored by Senator Borris Miles, D-Houston, to improve reporting of maternal deaths is on its way to the governor’s desk. But the task force now has only two years to use these new protocols, which supporters say is not enough time to finish their work.

Meanwhile, the Legislature barely addressed the lack of access to health care.

Texas has the highest uninsured rate in the United States, yet the state rejected a federally funded expansion of Medicaid that would have covered 1.1 million more Texans. The budget passed by the Legislature again underfunds Medicaid.

More than half of all births in Texas are paid for by Medicaid, but coverage for new mothers ends just 60 days after childbirth. The majority of the 189 maternal deaths the task force looked at from 2011 to 2012 occurred after the 60-day mark.

The task force recommended that lawmakers extend health care access for women on Medicaid from 60 days to one year after childbirth. One bill, from Representative Jessica Farrar, D-Houston, was filed to do so, and it didn’t get a committee hearing — probably a reflection of how little appetite there is in the Legislature to spend any more money on health care for low-income people. Representative Garnet Coleman, D-Houston, proposed screening and treatment for postpartum depression for mothers whose babies are on Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) plan. But the cost — $76 million over two years — kept the measure from coming up from a vote on the House floor.

A less ambitious version did pass the Legislature and is awaiting action from Governor Greg Abbott. The proposal, by Sarah Davis, R-West University Place, only offers postpartum screening, not treatment. One-sixth of all new mothers experience postpartum depression, and half of the cases go undiagnosed, according to a recent report.

“To say I’m upset would be an understatement,” said Representative Armando Walle, D-Houston, who wrote the House bill that established the task force in 2013. “I’m disappointed we couldn’t tackle this issue in a much more thoughtful way. We debated bathrooms all night. There are women dying.”

Correction: This story initially reported that no bills were filed to extend Medicaid coverage for new mothers a year after birth. A bill from Representative Jessica Farrar, D-Houston, would have done this, but it did not get a committee hearing. Representative Coleman’s bill would also extend coverage but didn’t get a House vote.