The $9 Billion School Finance Problem in Speaker Bonnen’s Backyard

While legislators focused on school finance and property taxes, a silent culprit continued to metastasize. If Chapter 313, a corporate welfare program, is left unaddressed, it could undermine any progress made this session, critics warn.

There’s a $9 billion (and growing) problem looming in the backyard of House Speaker Dennis Bonnen. That problem is formally known as Chapter 313.

As Texas’ largest corporate welfare program, it allows school districts to give big corporations steep discounts on property taxes for up to 13 years as a way to incentivize businesses to set up shop in the state. The forgone property tax revenue that districts would have used to fund their share of educating kids is covered by the state.

Such abatements have rapidly expanded in size and scope in recent years. By 2023, Chapter 313 — the program’s section in the state tax code — is projected by the state comptroller to cost Texas more than $1 billion a year in lost revenue. The more than 400 deals that are currently active are estimated to siphon $9.6 billion from state coffers over their lifespan. In effect, the state is spending more and more of the money meant for cash-strapped Texas schools on subsidizing industry.

At a time when lawmakers are scrambling to come up with the money to fund a major school-finance overhaul, Dick Lavine, the state’s foremost Chapter 313 critic, thinks it’s more important than ever to take a close look at the program, especially with its scheduled expiration date coming up in 2022. In short, Lavine thinks that ending or significantly curtailing the scope of the program is essential to any sort of long-term solution that increases the state’s diminishing share of education funding and reduces inequity between school districts.

“The Legislature has had to struggle mightily to fund even this session’s school-finance reform, and there are widespread fears that it will be difficult to continue [funding] into the future,” said Lavine, senior analyst at the Center for Public Policy Priorities. “One reason is that Chapter 313 is taking a billion dollars a year out of our school-finance system.”

But state lawmakers have resisted including Chapter 313 reform in the ample conversation this session about how to get the state to school-finance parity — and keep it there. In fact, Bonnen’s House went in the opposite direction in April, overwhelmingly voting for House Bill 2129, which extends the program for another 10 years without a single change. But as the session winds down, it looks unlikely that the Senate will take up Chapter 313 this session, setting it up as a significant issue in 2021.

Part of the reason the program is resistant to reform is that killing or shrinking it doesn’t provide an immediate revenue fix, like raising the sales tax or diverting money from the oil and gas severance tax — two measures that GOP lawmakers have pursued this session — would.

“The problem is these are long-term contracts. Even if [the program] were to expire at the end of 2022, it would be years before we start to see any benefits to the state,” Lavine explained. “But at least it would stop the bleeding and put us back on track to funding our schools.”

–

“It’s working,” said Representative Jim Murphy, a west Houston Republican, as he presented HB 2129 on the House floor in April, repeating a disproven claim that none of the abatement-incentivized businesses would have come to the state without Chapter 313. “As the argument goes, half of something is better than 100 percent of nothing.”

But Lavine and other tax-incentive watchdogs warn that it’s not working. In their view, Chapter 313 has become a bloated and ineffective slush fund that provides costly tax breaks to companies that would come here anyway, and that is draining the state of billions of dollars for public education.

Chapter 313 requires the state to pick up the tab for local school districts’ foregone property tax revenue, forcing legislators to find other sources of revenue to cover the abatements. Additionally, districts are free to sign side agreements by which the companies give the districts, on average, 30 percent of the tax abatement. All told, schools that have made such agreements have received more than $1 billion in supplemental payment through Chapter 313. That money, which otherwise would feed into the overall school-finance formula, does not factor into the state’s funding calculations. That means property-wealthy districts that participate don’t have to pay that share into the Robin Hood program — by which the state uses some revenue from wealthy districts to fund poor districts — further tilting the system’s scales.

Meanwhile, the Texas comptroller’s office, which oversees the program, acts like a rubber stamp. Up to 90 percent of the projects that received Chapter 313 tax breaks between 2002 and 2015 were likely to come to Texas anyway, according to a 2017 study by University of Texas at Austin professor Nathan Jensen. As the Observer has reported, companies have repeatedly received tens of millions of dollars in property tax breaks through the program despite publicly indicating that they were already planning to build in Texas.

Some executives have been frustrated at how adept its competitors have become at gaming the abatement. Jeffrey Beicker is the CEO of Permico Energia, a midstream pipeline company that initially had its 313 application denied in 2018 for insufficient evidence that the incentive was necessary for the company to build in Texas. “All these other companies have multiple press releases, quarterly reports, and annual reports that state their intentions,” Beicker said in an email to the comptroller’s office, according to the Houston Chronicle. “We refuse to lie to receive the tax abatement. Apparently our competitors do not share this moral dilemma.”

–

Nowhere are Chapter 313 agreements more prolific than in the state’s Gulf Coast region. The biggest beneficiary of the program has been the petrochemical industry, which has vast refining complexes spread along hundreds of miles of the coast. The program has left an indelible imprint in Bonnen’s House District 25, located at the epicenter of the state’s petrochemical corridor. Bonnen’s district includes Lake Jackson, a thriving company town developed by Dow Chemical in the early 1940s, as well as Freeport, an impoverished city that many have written off as a sacrifice zone for chemical pollution. A May 2018 Texas Department of State Health Services investigation into cancer clusters found an elevated presence of several kinds of cancers in Freeport.

“I call Mr. Bonnen the water boy for industry,” said Melanie Oldham, a longtime environmental and public-health activist who lost an uphill bid for for Freeport mayor earlier this month. “He does not care about our public health or environment in Brazoria County. … But he gives these industries corporate welfare and we pay higher property taxes. Ask Mr. Bonnen to explain that.”

Bonnen’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

Bonnen is one of the staunchest political allies of the petrochemical industry. Between September and December of 2018 — the period during which Bonnen became House speaker — Bonnen took in more than $160,000 from oil and gas interests, including corporate PACs and executives, according to an Observer analysis of campaign finance records.

The biggest beneficiaries of the Chapter 313 program are major corporations that have used these deals to expand existing facilities in Bonnen’s district. Combined, Freeport LNG, Dow Chemical and Chevron Phillips have received more than $1 billion in Chapter 313 tax breaks, according to a 2017 analysis of existing deals by the Houston Business Journal.

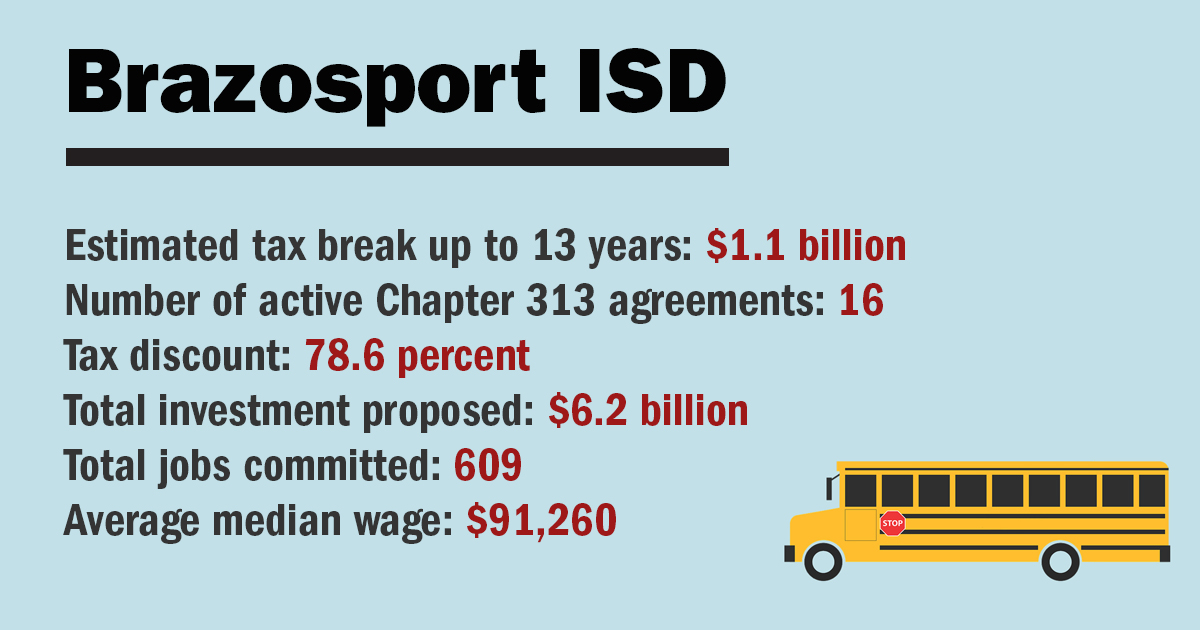

Two of the biggest purveyors of 313 deals — Brazosport ISD and Sweeny ISD — are also located in Bonnen’s district. Brazosport administrators have signed off on 16 deals that have delivered, over the course of 13 years, $1.1 billion in tax abatements to companies including Dow, Freeport LNG and Praxair, according to the Business Journal. In return, the district has received a windfall of supplemental payments that are protected from state recapture under Robin Hood.

Oldham said she’s brought her concerns about the program to the school district, and that officials told her it’s a big upside to be able to keep the money from flowing back into state recapture. The district, Oldham said, “tried to make it sound so wonderful, like, ‘We might as well give [the abatements] to them, since it helps us.’ The problem is that too many districts have that same attitude, and it’s dragging down the whole system,” Oldham said.

Representatives for Brazosport ISD did not immediately respond for comment.

Still, lawmakers from both parties see more political upside than downside to Chapter 313. So it wasn’t necessarily a surprise when just 22 Republicans — mostly affiliated with the far-right Empower Texans wing of the party — voted in April against the bill to extend Chapter 313. Only five Democrats opposed it, two of whom claimed after the fact that they had meant to vote in favor.

“Once you create a tax carve-out, it’s hard to get rid of the tax carve-out, because somebody benefits from it and they will always fight to defend it,” Representative Erin Zwiener, a first-term Democrat from Driftwood who voted against the extension bill, told the Observer. “313 passed overwhelmingly because they have been used in so many members’ districts.” While she says she opposes the program on principle, none of the school districts in her district utilize the program. “That gave me a lot more freedom,” she admitted.

–

While most lawmakers support the program, a wide array of policy analysts oppose it. The state’s two leading think tanks, the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation and the left-leaning Center for Public Policy Priorities, advocate ending Chapter 313 outright, as do the Texas GOP and Democratic Party platforms. Empower Texans also sees the program as an example of big government picking winners and losers.

The Senate largely shied away from a debate on the program this session. The House bill to extend the program as-is died in Senate committee, as did bills that would either abolish or scale down Chapter 313. Senator Lois Kolkhorst, a conservative Republican from Brenham, authored three bills this session that would curtail the program in different ways.

“What we currently have now is a disparate program that incentivizes property wealthy school districts to receive a 313 benefit,” Kolkhorst said at an April 9 Senate property tax committee hearing. “The state doesn’t get that current revenue. … My fear is that eventually we will end up with an inequitable system.”

Regardless, most Republicans defend Chapter 313 as an integral part of the Texas Miracle, and argue that the economic benefits generated by Chapter 313 projects far outweigh the cost of the abatements.

–

For years, powerful oil and gas players such as Chevron, Dow Chemical and Phillips 66 have plied Bonnen and other powerful lawmakers with campaign contributions. The average House member received nearly $38,000 between 2013 and 2016 from oil and gas interests, according to a Texans for Public Justice report.

In early May, I talked with Lavine and Vance Ginn, Texas Public Policy Foundation’s senior economist, in a hallway behind the Senate chamber. The former is a liberal policy expert, the other a conservative — and both have some political influence at the Capitol. But not when it comes to Chapter 313. I ask whether it’s industry influence that’s keeping lawmakers on board with a flawed program opposed by both party platforms.

Just then, Houston Senator Paul Bettencourt, the most influential legislator on property tax issues, came barreling down the hall with three of the state’s most powerful lobbyists in tow: Todd Staples, a former agriculture commissioner who now serves as president of the Texas Oil and Gas Association; James LeBas, who lobbies for the same group and for the Texas Chemical Council and a host of companies owned by Koch Industries; and Tony Bennett, head of the Texas Manufacturing Association.

All three have gone on the record in support of extending the Chapter 313 program, and oppose measures that would reform how the system works. “That’s a powerful bunch right there,” Ginn said as the quartet disappear into Bettencourt’s office.

“Those are the ones we keep talking about,” Lavine said: the “mean beneficiaries” of Chapter 313.