The Art of Looking

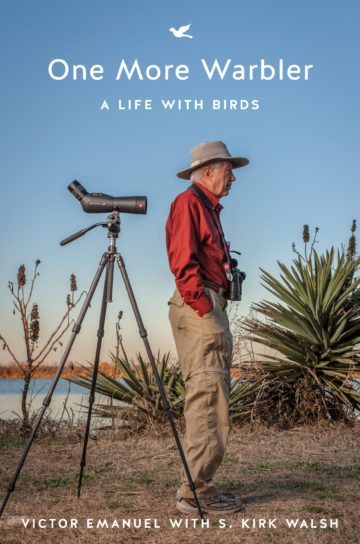

An afternoon with the king of birding in Texas, Victor Emanuel. His new memoir, "One More Warbler," hits shelves this week.

A version of this story ran in the April 2017 issue.

Across the river from the Austin airport, past forests and muddy banks, four retention ponds stand open beneath the sky. The wind is heavy with the sickly sweet smell of sewage; sludge dredged from the pond bottoms dries for recycling on slabs of concrete. The ponds contain a soupy mixture of freshwater and the sort of organic waste most people prefer not to contemplate too long. For nature enthusiasts, this is the Hornsby Bend Bird Observatory; for everyone else, this is the Hornsby Bend Biosolids Management Plant, and they keep well away.

Victor Emanuel is the first type of person. He stands on the grassy bank near the ponds, a tall, stoop-shouldered man peering into a spotting scope. Before him, fleets of ducks punt through the choppy water. They come in all shapes and sizes: tiny green-winged teal, resplendent in their patches of emerald feathers; larger shovelers bobbing on the wave crests; a single mallard looking slightly confused in this foreign company. Sandpipers peep quietly as they scamper over the tangled algae.

Emanuel knows them like old friends. He’s spent decades as a professional birder, leading clients on tours all over the world and sighting birds so rare they were thought extinct. Despite his globetrotting, he’s an old Texas hand; he grew up in Houston in the ’40s and has lived in Austin for many years. With his new memoir, One More Warbler, about to hit shelves courtesy of University of Texas Press, it seemed like a good time to talk with him about birding in a changing world.

Hornsby Bend is one of Emanuel’s favorite birding spots. “On an August afternoon with the sun at your back, you might see 12 different kinds of shorebirds,” he said. “Birds turn up here that are very, very rare in Texas.”

Part of the reason for that bounty is the nature of the facility itself. We tend to think of sewage as toxic, Emanuel says, but in practice, the sewage in the retention ponds is a nourishing bacterial soup for insects, algae and microorganisms. This, in addition to the relatively intact forests that surround the ponds, makes the site a tempting spot for migratory birds.

The migrations themselves are another part of the puzzle. Texas sits in the middle of several flyways, and the movement of birds across the state is like an intricate timepiece. Birds appear where and when there’s food, and then they’re gone. Hornsby Bend’s population changes throughout March, April and May as different species roll in.

Standing on the bank, Emanuel shakes his head. “One of the things that annoys me is when people from the North move down here and say we don’t have seasons,” he said. “Of course we have seasons. You just have to watch. Look at this teal.”

I set my eye to the lens and see a handsome duck dabbling happily in questionable mud. From far away the bird looks gray. But through the scope the gray stands revealed as an intricate lattice of fine black-and-white stripes.

by Victor Emanuel, with S. Kirk Walsh 295 PAGES; UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

Looking is something of a sacred act to birders, and many recall the moment they first truly noticed a bird. For Emanuel, it was the moment as a young boy when he saw a cardinal sitting on moss in his Houston yard, a splash of red against green. Soon he was looking hungrily at the other common birds around him. It was the warblers that caught his eye most often, with their bright colors and active, dancing movements. He became addicted to looking. At 16 Emanuel began organizing the Freeport Christmas Bird Count, a group competition to see how many birds could be counted in a single day. (He still organizes the annual count.) Birding is hunting with the eye, and the trophies are mental, memories of light on feathers or the shifting of color as a bird moves. I find myself counting sightings under my breath: American coot, killdeer, loggerhead shrike…

“People say the devil’s in the details,” Emanuel says, with the air of a man reciting a well-worn motto. “Well, the beauty’s in the details, too.”

Emanuel’s road to professional birding was a winding one. He taught classes in political science, organized school board elections and managed a friend’s congressional campaign. But politics wasn’t to his taste. In 1974, he founded Victor Emanuel Nature Tours, an early ecotourism company that has expanded by leaps and bounds over the last 40 years. Aside from the company, he still participates in counts, mentors kids and works to instill his love of birds in everybody he meets. He’s taken everyone from George W. Bush to Prince Philip out to appreciate nature.

“There’s a bird called the brown thrasher; it’s got a long tail and it’s very shy. In 1971, we saw 125. This year, we saw one.”

As we drive through the fields beyond the retention ponds, a hawk swoops over the truck, black-barred wings and tail striking in the dim light. We exit Hornsby Bend through a side gate and head down Platt Lane, an old, winding road. There are fewer birds here, and the twigs rattle in the wind. Walking into the forest, Emanuel muses on how birding has changed. As he’s grown older, he’s seen many species dwindle under the sustained assault of habitat loss and predation by cats. Some species — the brown pelican, the peregrine falcon — are thriving after intensive rescue efforts. Many others, smaller and less charismatic, are not. He recalls his birding mentors talking about something similar: a slow retreat, a dwindling. At the time he didn’t understand it. Now he does. Recently, he was going through some of the records from the older Freeport counts, looking at the sheer number of birds spotted.

“I made a mistake, looking at this list,” he says, shaking his head. “There’s a bird called the brown thrasher; it’s got a long tail and it’s very shy. [In 1971] we saw 125. This year, we saw one. I went down the list. Bird after bird like that. It was depressing.”

A turkey vulture swoops low, its black wings huge against the cloudy sky. We watch it go in silence. Bird-watching these days isn’t just about looking, Emanuel says. It’s also about bearing witness to a world that sometimes seems to be sliding slowly toward the brink. You look up at a certain bird, half-wondering if your grandchildren will ever see one. Once there were warblers, you might tell them, the same way you were told that once there were dodos, great auks, passenger pigeons. Beautiful, vibrant, everywhere. Then gone.

For now, though, Emanuel refuses to give up hope. “Birders are the luckiest people,” he tells me as we walk out of the forest. “If you’re interested in tropical fish, you have to go to where you can see them. … You want to see art, you have to go to an art museum. We don’t have to do any of that! Beauty is all around us. Birds are all around us. We can see birds everywhere. At least the ones that are left.”

This article appears in the April 2017 issue of the Texas Observer. Read more from the issue or become a member now to see our reporting before it’s published online.