The persecution for her work as a lawyer in Colombia had gotten so bad that Victoria and her husband, Anton, decided they needed to start lying to their son. They couldn’t stay in Colombia any longer, but they also recognized the dangers of fleeing—especially with their son, Felipe, who was 10 at the time. So they told Felipe the family was taking a vacation to Mexico. Maybe they would even get to go to the United States, they said.

It was all a ruse to keep their son calm, to protect them from people who might target them as they traveled through Mexico.

(Editor’s note: To protect the family’s identity for fear of further repercussions, we have omitted Victoria’s last name from this story; Anton and Felipe are middle names.)

Once they hit U.S. soil in late May, the family found Border Patrol agents and gave themselves up to ask for asylum, after which they were placed in detention to await processing.

“I’m sorry, my beautiful child,” Victoria recalled telling Felipe.

He was upset with his parents—they had lied to him; this was no vacation—but couldn’t contain his excitement about being in the United States.

“We weren’t running or hiding,” Victoria later said. “I brought evidence to show immigration officials in support of our asylum application and told the immigration officials about why we fled Colombia to save our lives.”

Despite her preparations, Victoria became nervous when, a few days into their detention, agents took Felipe away, saying that they were taking him to an appointment. He was gone most of the day. That evening, another agent brought him back; his mother hugged him tightly.

One or two days later, on or about May 29—the exact date is unclear—Victoria and Felipe were taken to another room from which they could see, but not speak to, Anton. After some paperwork and an interview, an officer told Victoria that they were taking Felipe to have a snack.

“They opened the door, took him away, and then closed the door,” Victoria said. She had heard about family separations, but didn’t think the U.S. government was still taking kids away from their parents.

Victoria sensed something was amiss and began asking officials where her son was. “I don’t know,” immigration officials told her repeatedly. Almost six months later, she hasn’t seen him.

More than 5,500 children, including breastfeeding infants, were forcibly separated from their parents during the Trump administration’s family separation policy, which began as a pilot program in El Paso in early 2017. On June 20, 2018, former President Donald Trump signed an executive order directing Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials to stop separating families, but the practice continued. In 2019, the Texas Civil Rights Project documented 272 cases of family separation. Most of those cases—223—were extended family members, including siblings, aunts, uncles or grandparents, or legal guardians or step-parents.

In January 2020, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) established select criteria under which children can in fact be separated from their families: Immigration authorities may only do so if they deem the parent unfit, if the parent is going to be prosecuted for a felony, if the parent is hospitalized, or other specific circumstances.

The incoming Biden administration promised to stop such separations for good and offer reparations for the previous administration’s harms.

But as the case of Felipe shows, immigration officials have continued to separate parents and children in violation of the policy. From the start of the new administration to August 2022—the latest month for which data has been published—U.S. authorities have reported at least 372 cases of family separation.

“We said never again, but here we are,” said Kassandra Gonzalez, an attorney at the Texas Civil Rights Project.

The Texas Observer has identified further cases not included in this count—including that of Felipe, whose case is not included in the tabulation from May. Felipe remains apart from his parents. The failure to account for the true scope of the problem means that not only is the public left without a complete understanding of the breadth of ongoing separations, but some cases—some children—have ended up lost in the system.

The Observer reached out to the White House and DHS for comment. The White House directed the request to DHS, which did not respond by the time of publication.

“This administration came in really trying to distinguish themselves on immigration policy. The main pillar of distinguishing themselves was that they would not carry out family separation,” said Jesse Franzblau, a senior policy analyst with the National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC). “They just have completely failed to actually live up to that promise to stop this—the most abusive, traumatic practice that can be carried out in immigration enforcement.”

“We said never again, but here we are.”

The Biden administration has neither halted family separations nor compensated past victims of the practice. Some of the architects of family separation have been promoted or continue in high-level positions under President Joe Biden in Texas and other states.

“The Trump administration began cruelly ripping babies and toddlers away from their parents and, unfortunately, there’s still an enormous amount of work to be done even to begin to repair the damage,” Lee Gelernt, deputy director of the ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project, told the Observer. “We must provide the separated families with a pathway to remain here and to ensure that safeguards are in place so this horrific practice never occurs again.”

“Those safeguards are not in place yet,” Gelernt added.

Family separations have continued, although at a slower rate, despite the Biden administration’s professed approach. Under Title 42—a Trump-era public health policy that allows for the immediate expulsion of migrants to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic—immigration officials need not adhere to the guidelines established to limit family separations. In February 2021, unaccompanied minors were declared exempt from Title 42 expulsions, although families are not.

In practice, this has allowed immigration officials to separate children from their relatives and guardians with impunity. Title 42 has been stretched far beyond its medical mandate.

“Under Title 42, it’s much more kind of just Wild West,” Franzblau said. On November 15, a federal judge vacated the ongoing use of Title 42, but then stayed that decision for five weeks. With appeals likely, its fate is still undecided.

Since the beginning of 2021, Immigrant Defenders Law Center has tracked more than 300 cases of non-parental relatives separated from children at the border. The minors were categorized as unaccompanied and exempt from Title 42, which allowed them to remain in the United States. Their adult guardians were sent to Mexico. Since the center only tracks cases of minors who end up in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) in California, the true number of these cases could be much higher.

This is what happened to Raquel Andrade and her 8-year-old grandson, Joseph Mejia Vallecillo, who arrived at the U.S. southern border in Hidalgo on April 23, 2021. They had left their home in Honduras a month earlier after losing most of their belongings in two of the worst hurricanes to hit Central America this century.

Joseph had lived with his grandmother in San Pedro Sula since the murder of both his parents when he was an infant. After spending four months drifting between shelters and the homes of friends and family, Andrade thought migrating might provide Joseph a better life and spare him from the fate of his parents and so many other young Hondurans.

“I thought the president [Biden] was giving opportunities to enter to work, and since I had my daughter’s death certificate, I thought that I could apply for a permit to enter the U.S.,” Andrade told the Observer.

But Andrade did not receive the warm welcome she had imagined for her grandson, who calls her “mom.” Instead, she said Border Patrol agents accused her of “stealing” Joseph.

Andrade presented birth certificates to prove her relationship with her grandson, death certificates and media reports to document his parents’ murder, and school documents showing that she is his guardian. But the Border Patrol agent didn’t care, she said.

“They told me that the child was staying with them, and I said, ‘No, you have to deport me with him,’” she recalled. “He started to cry, and he hugged me, but they practically took him from me by force.”

After desperately begging officials to keep her and Joseph together, she realized her pleas were being ignored. So she turned to Joseph and prayed for the best.

“Papi, in the name of Jesus, nothing bad is going to happen to you,” she told him.

Andrade was sent to Mexico. Days later, she was back in Honduras. She didn’t know where Joseph was.

When children are separated from their parents because they are to be prosecuted for a crime, typically it is for the crime of “illegal entry” or “illegal reentry.” The crime that Victoria and Anton are being charged with is a violation of 19 USC 1459(a), a U.S. code that requires people entering the United States—except if they are entering by plane or ship—to enter through a designated port of entry.

The other reasons immigration officials use to justify the separations don’t seem to apply in their case: health problems, questions about maternity or paternity, or criminal allegations against the parents.

The Texas Civil Rights Project has worked with six other families who have been separated under the Biden administration. Three of the separations occurred because the parents faced prosecution under 8 USC 1326, or “illegal re-entry.” One family they worked with had a 3-year-old who was separated from her parents from October 2021 until May 2022. Another client they worked with abandoned his asylum claim, opting to face the danger in his home country rather than continue apart from his child.

“It’s basically the criminalization of immigration,” Gonzalez said. “That’s the only reason these families are being separated.”

Peter Schey, executive director of the Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law, commented that “to keep a parent detained solely to face a misdemeanor charge is utterly irrational. The trauma that it causes is extreme. We know that from interviewing hundreds of children who were separated under Trump.”

Schey added: “It’s like using a nuclear weapon to target one person in a pup tent.”

“As long as they have this deterrence approach of trying to scare families from seeking refuge in the U.S. through punitive programs, they’re going to have separation.”

In May, the same month Felipe was separated from his parents, the Department of Health and Human Services documented 15 cases of family separation. The reasons for separation include lack of “parent fitness,” “parent criminal history,” and parent “referred for prosecution.” Four of those separations occurred because the parents were referred for prosecution. Biden administration officials were separating families using the same justification that the Trump administration used during the zero-tolerance policy.

According to the Rebekah Gonzalez of NIJC, family separations continue partly because Border Patrol agents—the first point of contact for most families crossing the border—still don’t have the knowledge and training to handle these cases. They don’t take time “to really understand the family unit and understand the best interests of a child.” Instead, they default to separation.

“We still have a system in which individual agents who have no background in child welfare are making these decisions without any sort of oversight,” said Jennifer Podkul, an attorney with Kids in Need of Defense. “There’s no check on their decisions at all.”

Franzblau of NIJC said that the problem goes much deeper. A lack of institutional overhaul—both among top-level decision-makers and the bottom-level CBP officials who encounter families at the border—means that the overall mentality toward immigration policy has not changed.

“As long as they have this deterrence approach of trying to scare families from seeking refuge in the U.S. through punitive programs, they’re going to have separation,” Franzblau said.

Enacted by President Trump and rescinded by President Biden, “zero tolerance” was another iteration of the longstanding Border Patrol policy, in place since the 1990s, of “prevention through deterrence.” The idea is that forcing people into dangerous or “hostile terrain” or delivering “consequences” such as criminalization for unauthorized border crossings will dissuade people from migrating. But, especially for asylum-seekers, the risks of danger or prison time are worth it. Decades of studies have shown that people fleeing persecution, hunger, extreme violence, or are seeking to reunite with families will continue to cross borders despite hardship or possible punishment. The months following the most publicized outrage over family separation in 2018 actually saw an increase in families attempting to cross the border.

“‘Zero tolerance’ was a very clear policy and practice in order to deter individuals from coming to the United States. And so I think because it was a clear directive and the intent was clear, individuals saw it as a more cruel act because of the intent,” said Margaret Cargioli, directing attorney at the Los Angeles-based Immigrant Defenders Law Center. “The effect and impact of family separation that we see in smaller numbers does not gain the same amount of attention. However, it should gain the same amount of sympathy because it has the exact same impact that zero tolerance had on the children that were separated from their families.”

Andrade describes the time that Joseph was in U.S. custody as “agony.” Some days, she couldn’t eat or sleep.

Joseph doesn’t like to talk much about his time in the United States. Mostly, he complains about the strange food like the cold, gray shrimp he had never seen before. He missed his grandmother’s tripe soup.

Communication between the two was sparse. They would usually talk on the phone once every eight days. But, Andrade recalled, when Joseph didn’t do his chores, like making his bed, sometimes officials would punish him by not allowing him to call his grandmother.

“He was always asking to talk to me, and the [man in charge] told me to tell him that it wasn’t possible because he wanted to talk every day,” Andrade said.

A family friend was willing to be Joseph’s sponsor in the United States. so he could be released and try to stay there. But since she wasn’t a blood relative, a lawyer explained to Andrade that there was a possibility Joseph would be released to foster care instead.

“How is someone else that he doesn’t know going to raise him?” Andrade asked. “I said, if there is a chance that they give me permission to return to the U.S., then he can stay, but if not, then he should return here.”

Ultimately, Joseph had a say in his decision. He could start over in the United States, free from the gang violence his grandmother wanted him to escape. But he would have to do it without the woman he called mom.

Joseph said he wanted to be with his grandmother, so the lawyers requested voluntary departure, the fastest way to get him back to Honduras. But even that often takes months, and Joseph had to wait in a shelter he didn’t like very much. “We spent all our time shut inside,” he recalled.

In July 2021, after three months spent separated from his grandmother, Joseph finally boarded a plane to return to Honduras. He was excited to fly and look at all the tiny houses “small like ants” down below. It was a happy day, he recalls. “Because I had come back to my family,” he said.

But he was also returning to danger. Since the family has been back home, another relative has been murdered.

Although they’re happy to be together again, the experience changed Joseph, his grandmother said.

“Before we left, he was a very charismatic and happy kid,” Andrade said. “He only thought about playing and singing.” Now, he has moments of depression that make his grandmother worry that he might want to hurt himself. “It scares me,” she said.

Other families have an even harder time reuniting.

Once the U.S. government separates a child from their family, it must then reunite the child with a responsible guardian or relative as soon as possible, according to policies stipulated by the Office of Refugee Resettlement—the HHS sub-agency tasked with protecting migrant children who are either alone or are taken from their parents. That can end up being a strenuous month- or years-long process for families.

It took a month for the ORR to even realize that Felipe still had parents from Colombia who were being detained in the United States. After over 30 days of no contact, an ORR official called Victoria and asked if she had crossed into the United States with a child. If it weren’t for Felipe himself explaining what had happened, attorneys at NIJC, an immigrant rights group that took on his case, wouldn’t have known he had arrived with his parents.

“There was confusion that ORR thought he was found alone in Mexico,” said Daniela Velez, an attorney with NIJC. “This is such a big deal. This is Felipe being taken away from his parents, and no one can explain why or how.” The government has yet to be able to tell her why they separated the parents.

The Observer reached out for comment to ORR, which did not respond by the time of publication.

A DHS Office of Inspector General report from September 9 found that the department had failed to properly institute previously recommended protocols to track children who were separated from their parents. The report found one 10-month-old who was erroneously listed as “unaccompanied” despite having crossed with both parents. NIJC believes this misclassification is common.

For leaders of nonprofits like Justice in Motion, which has been working to identify and reunite families that were separated under Trump, it’s hard to believe that an administration that has promised to reunify families continues to tear them apart. Their network of lawyers and defenders sometimes only have a name and country of origin to start their search. From there, they trek through Central America’s mountains and dusty roads to find deported parents.

Most of the cases they track began in 2018, the most “chaotic” time in family separation, according to Justice in Motion legal director Nan Schivone. The government had no systematic way of keeping track of these families. They didn’t prepare a standardized set of basic questions—such as an address, phone number, and close family members—that would help them identify deported parents down the line. When kids were sent from the Border Patrol to other agencies, such as ORR, the agencies didn’t share basic information about the children’s parents or caregivers that would allow them to establish contact.

“They had no intention to reunite the families, and you can tell that by the way that they effectuated the separations,” Schivone said of the Trump administration.

This year, Justice in Motion’s work expanded to include a new element. The Biden administration launched a task force on the reunification of families, which states it is “the policy of my Administration to respect and value the integrity of families seeking to enter the United States.” Now, when immigrant-rights advocates find parents, they can explain to them that they have the option of legally migrating to the United States to reunite with their children who already are there.

“I credit the Biden administration for creating this task force to have a hand in repairing the harm,” Schivone said.

The Biden administration also recently launched a pilot program at a Border Patrol station in Texas to reunify adult relatives and children more quickly. Congress also allocated $14.55 million to DHS to hire child welfare professionals to work alongside CBP officers in its FY 2022 budget.

A DHS spokesperson told NIJC attorneys that when children are separated from their parents, “We provide parents with information about how to locate and contact their children once they are released or transferred to the custody of a different agency.”

That didn’t happen in Felipe’s case. His parents had no contact, explanation, or even knowledge of where Felipe was or how he was doing for more than a month.

Since late May, Felipe has been living in an ORR shelter in Chicago while his parents and uncle remain in U.S. Marshals’ custody in a privately run Texas prison. More than a thousand miles away from the only family he has in the United States, Felipe has been struggling to cope with his new surroundings. When his attorneys first met him at the shelter, they found him energetic and determined: Despite the difficulty, he was sure he would soon be reunited with his parents. But as the months dragged, he began to lose his spirit.

“Felipe was the brightest, most bubbly 11-year-old you’ve ever met,” Velez said. (Felipe had turned 11 in custody.) She added, “Now I’m seeing the transition of what a detention center can do to you.”

“He’s all about being brave. ‘I’m really tough,’ he says. But you can see the sadness, the hopelessness,” Velez said. She said she struggles to explain to him why he can’t be with his parents when they are all here, in the same country.

According to a declaration submitted on Victoria and Anton’s behalf by NIJC, “To date, neither DHS nor DOJ has provided Victoria or her attorney with any written explanation as to the basis for the separation, nor have any charges been brought against her other than the one relating to manner of entry. Put simply, this devastating separation persists with no justification whatsoever provided to the family.”

“He’s all about being brave. But you can see the sadness, the hopelessness.”

Not only has communication been sparse or broken between Felipe and his parents, but also between attorneys and his parents. Colleen Kilbride, senior attorney with NIJC’s Family Integrity Project, described the extraordinary efforts she’s had to go through to be able to speak with her clients. GEO Group—one of the largest private prison companies in the world, which manages the detention center where Felipe’s parents are being held—has repeatedly canceled, rescheduled, or been “super slow” or unresponsive to her attempts to schedule attorney calls. After futile back-and-forth with a secretary and a GEO “caseworker” when she was trying to reach Anton, she was finally told to contact the U.S. Marshals.

The answer from them, however, was that she could discuss anything she wanted with her client after his next court date at the end of January.

Biden’s Family Reunification Task Force hasn’t been much more helpful. Kilbride reached out to them on September 26 for help reuniting the family or at least facilitating communication between them and their attorneys. Almost a month later, on October 21, they responded curtly, encouraging her to file a complaint with the Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL) branch. Kilbride already had filed a CRCL complaint almost a month prior but has received no substantive response.

Since they were first able to speak by phone in June, Felipe’s parents have only been permitted 15-minute phone calls once a week. By early September, Felipe has stopped wanting to speak with his parents. He feels abandoned.

“You can’t even imagine how painful it is,” Victoria said. “I’m so down, sometimes I can’t eat. I never imagined I’d have to go through something like this. We came to ask for asylum.”

As Victoria was describing her son not wanting to speak to her anymore, she began breaking down. Felipe had been telling administrators that he was really sad, she explained, that he wanted to get out, that he kept seeing other kids who were able to leave. “I just tell him to be strong, that we’ll be together again soon. That we love him so much. That he’s not there because we don’t love him.”

Reflecting on his experience after four months of separation from his parents, Felipe told his lawyers in late September, “I’ve been away from my mom and dad for around four months. I don’t understand why I cannot be with them. I am filled with sadness.”

He added that he was struggling with “wanting to be alive.”

When asked about how Victoria was doing during the few attorney-client calls Kilbride was able to set up with her client, she said, “Not good. She was just weeping.”

“My suffering is so large I struggle to put it into words,” Victoria said.

Reflecting on her stint so far in prison, Victoria said, “I have never been detained before in my life. We are a law-abiding family. No one in my entire family has ever been in jail. I’ve helped people in jail as an attorney in Colombia, but this is a totally different experience of helplessness. It’s one thing to be put into prison when you’ve committed a crime, but it’s another thing when you’ve come to ask for asylum.”

In mid-September, before one of their weekly 15-minute phone calls, Victoria had forgotten to put on a white sweater that she wears for video calls with Felipe. She’s still trying to keep yet another fantasy alive for her son: that his parents are not in prison.

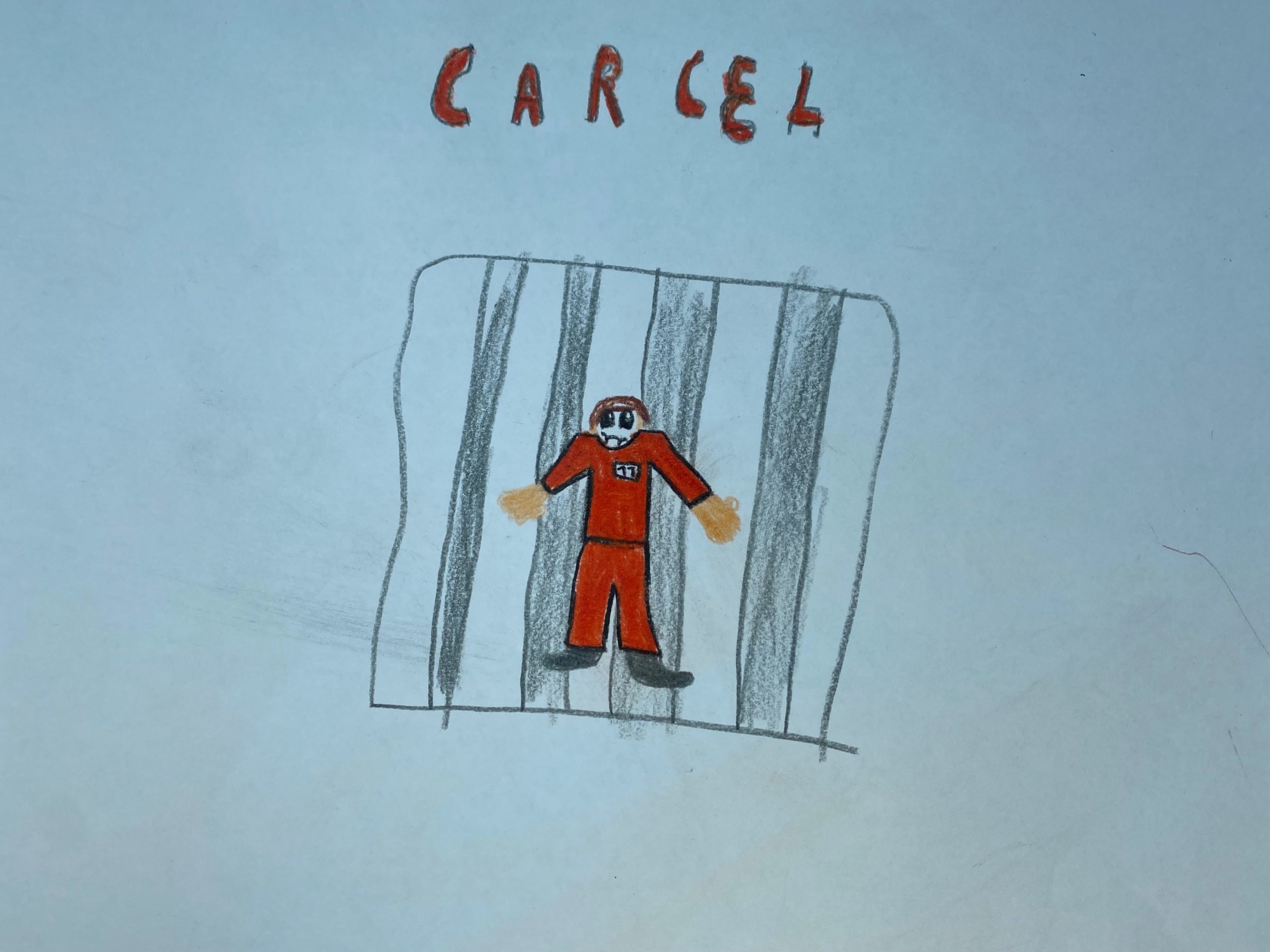

When Felipe saw her, he asked about the jumpsuit. You’re in prison, he challenged her. She tried to play it off and say that it was just a uniform they gave out in the shelters where she is staying, but she noted that Felipe is a smart kid. A few days later, he drew a self-portrait in which he is wearing an orange jumpsuit with a number.

Unless his parents are unexpectedly released, he will have to wait until late January, at the earliest, when Victoria and Anton have their court hearing, before he’s let out of his own prison.