Adult day cares in the Rio Grande Valley are a cultural phenomenon. What can they teach us about health and wellness in an aging world?

–

by Daniel Blue Tyx

@danielbluetyx

January 8, 2018

“La calavera,” the caller intoned, as Beatriz García placed a turquoise glass bead over the skull-and-crossbones icon on one of the two brightly colored cards on the table in front of her. It was 9 a.m. on a Tuesday morning at Lindos Momentos Adult Day Care in McAllen, and the chalupa — a bingo-like game featuring iconography drawn from Mexican folklore — was already in full swing.

Beatriz, 74, has five children and worked for 21 years in a local elementary school cafeteria. Her husband, Guillermo, sits at her side. He’s 80 and picked cotton for 25 cents an hour as a migrant farmworker in his youth, and later worked as a handyman. When they both retired in 2004, they tried staying at home, but found it hard to manage on their own due to Beatriz’s bad knees, Guillermo’s health woes, including quintuple bypass surgery, and their youngest son Ray’s schizophrenia and depression. So they decided to give adult day care a try.

“Guillermo didn’t want to come,” Beatriz remembered. “But he came, and he liked it, and now I can’t get him to stop.”

“This is our second house,” said Ray, 51, who is on disability and lives with his parents. Like nearly everyone at Lindos Momentos, he carries his own personalized chalupa kit in a leather pencil case that includes cards, beads and a feather for luck. “I come here to clear my mind, and just be around people. When you’re at home by yourself, you get lonesome.”

The Garcías are three of an estimated 34,200 Texans who utilize what the state officially calls Day Activity and Health Services, but are known in the Rio Grande Valley as adult day cares. These are facilities that offer social activities, health monitoring and assistance with daily living that enable older or disabled adults to continue living in their homes, and often provide a needed respite to family caregivers.

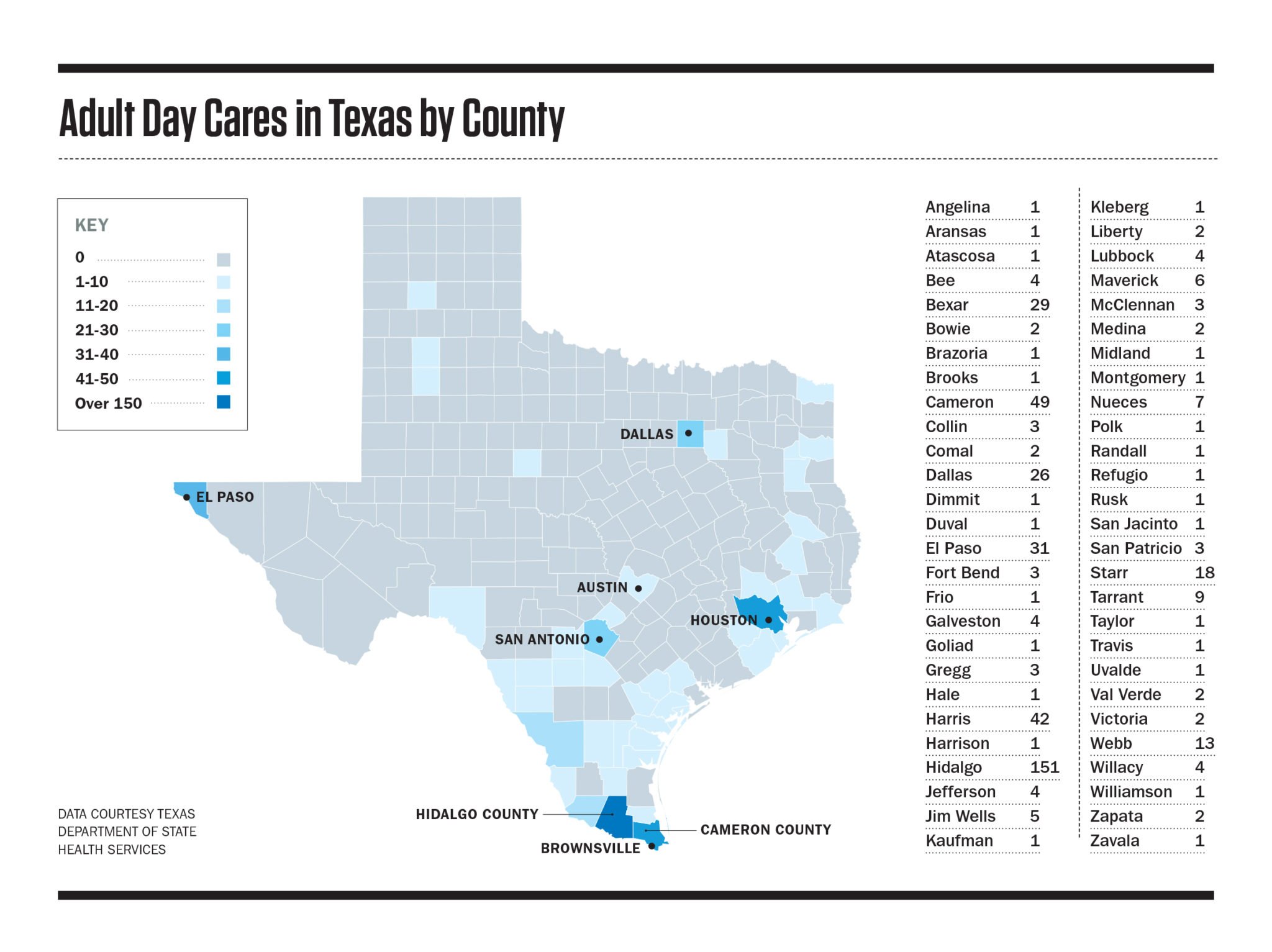

Lindos Momentos, which roughly translates to Precious Moments, is one of 223 such centers in the Valley, many with similarly uplifting names like Mi Casa (My House), Nuestra Familia (Our Family) and Fuente de Juventud (Fountain of Youth). There’s a running joke in the Valley that you can find an adult day care on every street corner. While it’s an exaggeration, statistics show just how ubiquitous they really are. The Valley is home to 40 percent of the adult day care centers in Texas — twice as many as in metro Houston, Dallas, San Antonio and Austin combined. Nationally, almost 1 in every 20 centers is in the Valley, even though only 1 in 250 Americans live here.

The prevalence of adult day cares in the Valley, which is 90 percent Hispanic, is part cultural, part economic. Hispanic seniors are more likely than Anglos to live at home with their children or other family members. The Valley also has a persistently high poverty rate and a percentage of seniors with diabetes, heart disease, depression and dementia that is alarmingly higher than the national average. This points to a paradox: Despite higher rates of chronic illness nationwide, Hispanic seniors have a significantly higher life expectancy than Anglos or African Americans, in part due to robust networks of family and social support. While a 65-year-old Hispanic senior can expect to live to 86, on average he or she will spend almost half those years living with serious physical or cognitive impairment that necessitates the kind of low-level long-term care an adult day care can provide.

Adult day cares like those in the Valley can offer a kind of middle way between round-the-clock care by family caregivers — who frequently burn out and experience physical and mental problems themselves — and expensive, sometimes impersonal nursing home care. As more seniors opt to “age in place” by living at home longer, such facilities are growing in number outside the Valley as well. Nationally, the number of adult day care participants has increased 63 percent since 2002, even as nursing home occupancy has flatlined. If this trend continues, the Valley today may offer a glimpse at what health care for older Americans will look like in the future.

“If you ask most folks what they want, regardless of their heritage and their ethnic background, they’ll tell you it’s to live at home longer,” said Amanda Fredriksen, director of advocacy at AARP Texas. “We need to try and figure out how to make that happen in a way that’s cost-effective and supports family caregivers.”

One such caregiver is Sylvia Solis, Beatriz and Guillermo García’s daughter. She uses the time while they’re at adult day care to transport her grandchildren to and from school, where she’s a volunteer, and to go to her own doctors’ appointments. Every evening, she drives across town to check on her parents and brother. “I love my parents,” Solis said. “I’m glad that they’re still with us at their age, and that they can take care of themselves. We all say that it’s because of the day care. They keep them busy, they keep their minds active, and that keeps them going.”

–

Lindos Momentos is situated in a nondescript storefront in suburban McAllen that it shares with a yoga studio and a pediatric clinic. The day begins at 6 a.m. when the cooks arrive to start preparing breakfast, which on the day I visited was migas along with black beans, oatmeal and bottomless coffee. By 6:30, the center’s 15-passenger white vans are making their first run to pick up members, who begin trickling through the doors around 7:00.

By the time I arrived, most seats at the folding tables spread out across the tile floor of the main gathering space were taken. Since the center is near its 95-person capacity, the empty seats belonged to those who had taken advantage of the center’s transportation to doctors’ appointments and shopping destinations including H-E-B, the Dollar Tree and the Mission pulga, a popular flea market.

I was greeted by Bertha Villagomez, the center’s owner and director, who was sitting near the door with several members, chatting in Spanish. Elegant in a silver scarf that matched the color of her hair, with silver jewelry and eye shadow to match, Villagomez evoked the figure of a matriarch on a telenovela — a comparison reinforced by the center’s unexpectedly upscale decor, such as a collection of flashy mosaic-framed mirrors. “We want it to feel exclusive, VIP,” she told me.

Villagomez, who holds an advanced degree in psychology from a Mexican university, started Lindos Momentos eight years ago with her two daughters. Before that, she worked as a director for other adult day cares, and owned a clothing boutique.

After a few minutes, her daughter Lucia Salinas, a licensed vocational nurse, joined us at the table. Dressed comfortably in a black cotton dress and gray leggings, she greeted each member by name as they passed through the door. “A lot of these people don’t just need a place to come to, they need someone to talk with — and that’s our job,” she said.

Ninety percent of the members at Lindos Momentos are enrolled in Medicaid, which pays for their care. The research suggests that adult day cares are cost-effective; they delay more expensive nursing home care and offer opportunities for social connection. Loneliness is correlated with loss of mobility, motor function and onset of dementia. “If you want to save the government money, this helps in a lot of ways,” Salinas said.

Adult day cares in the Valley wouldn’t exist without Medicaid, but the region’s high rate of enrollment doesn’t entirely explain their ubiquity. After all, there are substantial low-income and chronically ill populations in many of the state’s larger urban centers with proportionally fewer adult day cares.

“It’s become sort of a cultural phenomenon,” said Jacqueline Angel, a sociology professor at the University of Texas at Austin who studies Latinos and aging. “A sense of community is embedded into Mexican-American enclaves, especially among the immigrant community. Because there’s such closeness along the border, it’s a popular option — they’re very culturally appropriate.”

Fredriksen of AARP Texas points out that the number of assisted living facilities in the Valley is remarkably low. “I think that’s a reflection of cultural norms and the fact that folks take care of family at home,” Fredriksen said.

Salinas invited me on a tour of the facility, beginning with the “living room,” an adjacent suite where a nonverbal young man was on a couch, watching cartoons. Though Lindos Momentos primarily serves seniors, its members range in age from 21 to 98. Many of the younger members have developmental disabilities. When Salinas said good morning, the man took her hand and kissed it as though she were a queen. “That’s how he communicates with me,” she explained. “We go through this every day.”

Elsewhere, there were two computers with internet access, another TV showing the news, pool and pingpong tables, and an arts and crafts area. A member who is an artist by training teaches a monthly acrylic painting class.

Outside, in a patio space decorated with deck furniture and potted plants, Kathy Hood sat by herself. With her buzz-cut white hair, AC/DC tattoo and nose stud, she didn’t resemble most of the other members — in part because she was the only Anglo I met, but also because the crowd was generally buttoned-down. “Just chillin’,” she said, smiling.

Hood, who is 59 and disabled, moved to the Valley from North Texas a decade ago to take care of her parents, who were snowbirds. Before that, she was a cook at a truck stop and a nursing home. Her mom and dad passed away in early 2017 within two months of each other.

“My neighbor talked me into coming,” Hood told me. “I don’t speak Spanish, and I didn’t think I’d like it. But in my house, I’m there with the curtains closed, and all I do is sleep. It’s good for me. To be very honest, I love this place.”

–

On the other side of McAllen, in a newly developed area where medical offices and churches are still interspersed with farmers’ fields, another model of eldercare is taking shape in the Valley. The moment I walked into Cross Roads Senior Center, I was greeted by pulsating music and 28 seniors sliding and twirling across the floor. Cross Roads offers social connection, the largest benefit of traditional adult day care, alongside a more active, research-driven approach to wellness — and it may point the way to a health care future tailored for a new generation of seniors.

“Think you can do that?” Letty Guzman, Cross Roads’ director, challenged me as the dancers executed perfectly coordinated pirouettes to the tune of a Cherry Poppin’ Daddies swing number.

“No,” I answered truthfully, “definitely not.”

The Zumba class was the second offering of the day. Most of the dancers, many wearing neon-green “I am Seniorific” T-shirts provided to new members after their first month, had already walked 3 to 5 miles in the early-morning Caminata walking class. To the side, others were making use of the senior-specific exercise equipment, including treadmills adapted with fall-prevention technology, and back-supporting recumbent stationary bikes.

“This is a lifestyle center for the older population — a mini-gym,” Guzman told me. “It’s not an adult day care, at least in the traditional way that we know them here in the Valley. These are very active people, not ready to go sedentary. Honestly, it’s the way we see the aging population today: very active, very healthy, very engaged.”

Cross Roads is a joint project of the Lower Rio Grande Valley Area Agency for Aging and the WellMed Charitable Foundation, the not-for-profit arm of a physician-owned network of primary-care clinics highlighted for its work in cutting costs through preventive care in a 2015 Atul Gawande New Yorker article set in McAllen. The WellMed clinic next door refers many patients to Cross Roads, though any Hidalgo County resident over age 60 can use the free service. (A similar center in Harlingen serves Cameron County in the Valley’s eastern half.)

In addition to its gym, the center offers a computer lab, education classes and support groups on subjects such as fall prevention, managing chronic illness and stress management for caregivers, and BrainSavers, a popular 52-week course developed by neurologist Paul Bendheim to help seniors mitigate memory loss. “All of our programs are evidence-based,” Guzman said. “I will tell you that here we only do bingo once a month.”

Guzman is a past director of the local Alzheimer’s Association, and works as a consultant for several adult day cares. She acknowledged that Cross Roads, which doesn’t offer transportation or meals, serves a population that’s generally healthier and more independent than those of typical adult day cares. Still, Guzman feels many centers could be doing more to promote physical and mental wellness. “We have to find activities that are meaningful,” she said. “We have to get past just sitting there.”

She was particularly critical of the grouping of developmentally disabled young adults with an older population that has different physical and cognitive needs. “I do like inclusion a lot,” she said, “but I’m not OK with a lifestyle where a person in their 20s is going to age in a facility and not have someone teach them independent skills. Where’s the benefit?”

Guzman also raised concerns about the ability of some adult day cares to provide for the basic safety of their members — a warning that’s supported by an Observer analysis of state records. Lindos Momentos’ spotless record is an exception: In fiscal year 2016, the majority of McAllen adult day cares had multiple health violations in areas such as inadequate staffing, lack of safety procedures and substandard building conditions. Statewide, only five fines, totaling $31,800, were levied against adult day cares, compared to 693 complaints and incidents, including 20 categorized as representing “imminent danger” and 217 with “high potential to cause harm.” Most violations — even chronic and severe ones — are not fined at all. The handful of penalties levied “are just slaps on the wrist,” said Brian Lee, executive director of Families for Better Care, an Austin-based long-term-care watchdog.

The situation mirrors that of nursing homes. A January report from AARP Texas called “Intolerable Care” found a similar pattern of unaddressed violations, the vast majority of which were concentrated at about 25 percent of nursing homes that were serial offenders. If anything, Lee says, oversight at adult day cares is even more lax. “The inspection frequency, the statutes, and the oversight are not as tough as they are for the nursing homes,” Lee said. “[Nursing homes] get all of the attention — not just all the enforcement attention, but all the media attention as well.”

At Cross Roads, membership is growing by more than 30 seniors a month even though Guzman doesn’t advertise. The classes, which are on a first-come, first-served basis, have begun to fill up, and occasionally people are turned away or must wait for the next one to start. For Guzman, that’s a sign of the need for more services that promote a holistic approach to wellness.

One example of such a program is the PACE (Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly) model — currently implemented only in El Paso, Lubbock and Amarillo — which Fredriksen of AARP Texas described to me as “adult day care on steroids.” The program integrates adult day care and primary health care under one roof by pooling Medicaid and Medicare benefits. That way, doctors, therapists and activity directors can work directly together to craft individual plans of care for chronically ill patients.

Fredriksen thinks that adult day cares, particularly those that offer specialized health services, will continue to grow in number nationwide as more seniors opt to age in place — provided the centers adapt to changing expectations about aging and wellness.

“Alternatives like adult day care are a whole lot less expensive if you’re trying to think about how to stretch limited dollars, and they play an important role in helping folks stay independent and out of institutions,” Fredriksen said. “But when you think of the people who you know who are the next generation, is this what they’re going to want?”

On their way out of the dance class, Raquel and Leo Rocha stopped to chat. Raquel, 68, was wearing a T-shirt her husband had hand-drawn featuring the elderly sunglasses-wearing comic-strip character Maxine in a Zumba outfit. “I’ve been coming here since it opened four years ago,” she said. “If this wasn’t open, I’d be home alone.”

“We see coming here as preventive care,” said Leo, 68, who recently retired from a career as a hospice social worker. “I know that at my age, if you don’t use it, you lose it. You’ve got to stay active, and stay connected.”