The Doctor is Out

Bowie had one last chance to save its community hospital. Then anti-tax activists launched their campaign.

At 7 a.m. on a drizzly Monday morning in mid-November, dozens of Bowie residents gathered outside the hospital to say their goodbyes. After more than a decade of financial trouble, Bowie Memorial Hospital was shutting its doors.

Co-workers and friends cried as maintenance staff scratched the hospital’s name off the emergency room doors. Administrator Lynn Heller led the group of former employees, hospital board members and supporters in the Lord’s Prayer before rounding the corner to the front of the one-story building to lower the American flag one last time.

The sounds of a teenager playing “Taps” on his trumpet rang out in downtown Bowie, and then staff locked the doors.

After 50 years of treating patients in this North Texas town of 5,000, Bowie Memorial had been laid low by shaky finances and the indifference of citizens. Two weeks before the closing ceremony, voters went to the polls in Montague County to decide whether to approve a hospital tax district, which would have pumped much-needed revenue into the hospital. Run by a volunteer board appointed by the Bowie City Council, Bowie Memorial had hemorrhaged millions over the years as administrators struggled to serve an aging, poor and underinsured population. But anti-tax forces in the community saw the district as another government bailout; some didn’t even believe the hospital would close.

While “Taps” played at the closing ceremony, Charlie Pittman, who lives three blocks away, was just starting her day. Her son Cole’s three therapists had arrived for their weekly appointment, a welcome distraction from the sad scene down the street. When he was born, Cole had a stroke that left him paralyzed. Now a blond, blue-eyed 2-year-old, he suffers from epileptic seizures, is susceptible to high fevers, and needs intensive therapy.

The location of Pittman’s home is no accident. She and her husband wanted to live close to the hospital in case Cole needed immediate medical attention. In 2014, they bought the lot and had their ranch-style home custom-built with wide halls and doorways and ramps to accommodate Cole’s walker.

Pittman, a stay-at-home mom who takes care of her son around the clock, voted for the hospital tax, but largely stayed out of what became a vicious campaign that pitted neighbor against neighbor, friend against friend, and family member against family member. When the hospital closure became a reality, Pittman and her husband, both of whom grew up in the area, decided it was time to leave Bowie. Within weeks, their house had a “For Sale” sign outside.

“We used to go to sleep at night and be reassured… if something happens, we’re right here,” Pittman said. Letting Bowie Memorial die “wasn’t personal, but it kind of felt like that. You can’t thrive in a town when you don’t have a hospital.”

[Hear Charlie Pittman discuss losing the hospital.]

In 1966, the year after the Medicaid program was created by President Lyndon B. Johnson, Bowie Memorial opened its 49-bed facility. It was the largest hospital between Fort Worth and Wichita Falls — a health hub for the little towns that dot the stretch of North Texas between Fort Worth and the Red River. At the time, two full-time surgeons served on the medical staff, and the hospital provided intensive care and obstetric and home health services. All were later shed when the hospital began to struggle.

For decades, Bowie Memorial made a profit without tax support. Then, in the ’80s and ’90s, in reaction to rising health care costs, Congress began slashing Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates, as well as direct funding for rural hospitals. That left Bowie Memorial with the same kind of problems that many community hospitals developed. With the migration of young people to cities, Bowie Memorial’s patient profile grew older, poorer and sicker, with more people relying on Medicaid and Medicare or lacking insurance entirely.

By 2011, as many as 80 percent of Bowie Memorial’s patients were on Medicaid or Medicare. Then Texas refused to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, leaving almost 1 million low-income Texans uninsured.

Texas leads the nation in the rate of uninsured at 19 percent; in rural counties, that figure can reach an astounding 40 percent. When poor patients can’t pay, hospitals often have to eat the cost, known in medical parlance as “uncompensated care.”

Texas could’ve mitigated the problem by expanding Medicaid under Obamacare. Instead, by rejecting the expansion, the state put hospitals in a double bind. Not only do the uninsured keep showing up in ERs, Obamacare also cuts reimbursement for their uncompensated care by 35 percent.

Kevin Reed, an attorney who represents Bowie Memorial and other rural hospitals, describes what happened to Bowie as a “perfect storm” that won’t end soon. “I still think we’re going to continue to lose more” rural hospitals, said Reed. “Everything is hitting all at the same time.”

Since 2010, 68 rural hospitals have closed nationwide, including 13 in Texas, according to the University of North Carolina’s Rural Health Research Program.

By the mid-2000s, Bowie Memorial began losing hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. Like many other rural hospitals at that time, Bowie Memorial looked to local tax revenue to stay in business. “You have a high fixed cost with low volume, that’s the nature of the business,” Reed said. “In many circumstances, it’s not possible to make that operationally successful without local tax support.”

In 2011, voters in Montague County were asked to approve a hospital tax district, which would have been able to levy taxes of about $2 million each year. The timing couldn’t have been worse. By then, the tea party had erupted as a political force and the public mood turned sour on government. In Bowie, opponents of the hospital district pushed an anti-tax message, arguing that “if the hospital can’t work within their business plan to be self-sufficient, then they should close down,” according to a post on the online forum Topix. The measure lost by 671 votes.

After the defeat, Bowie Memorial officials warned that the hospital wouldn’t make it without tax dollars. From July 2014 to May 2015, Bowie Memorial reported $3.7 million in debt and uncompensated care. Administrators scaled back home health and hospice services and laid off more than a dozen employees. Then last spring, officials decided to try once more to get voters to approve a hospital district. If the tax didn’t pass, they warned, Bowie Memorial would close.

Ann Smith, a retired software engineer, wasn’t buying the dire predictions. As far as she was concerned, the hospital didn’t need tax dollars to keep operating. What its officials described as declining revenue due to decades of government cuts, she saw as “bad management.”

The hospital board wasn’t proposing a heavy tax — 17 cents per $100 in home value, so the owner of a $100,000 house would pay about $170 a year to support Bowie Memorial. Still, Smith argued, Bowie residents simply didn’t need “another tax. … It was an unfair tax at any rate,” she said, adding that the city and county had already raised taxes in 2015. “Don’t you think that’s enough? We are taxed enough already.”

In June, Smith joined Bowie’s anti-tax crusaders, business owners, retirees and others billing themselves as the “No BMH Bailout” campaign. With yard signs and mailers, they trumpeted a “no taxpayer bailout” message. They targeted senior citizens, who, they warned, would be taxed out of their homes. They circulated a YouTube video, which asserted that hospital administrators were trying to “fool the voters,” and likened Heller to President Obama, Nancy Pelosi and Harry Reid.

By then, disagreement over the hospital had turned into a town brawl. Heller left his job as administrator in July to run the “Save BMH” campaign. Over the next four months before the election, he held seven public meetings to educate voters on the financial state of the hospital and the tax rate. Hospital employees spent hours on the phone, encouraging voters to turn out for the November 3 vote. Jan Graham, health information management director, spoke to some 120 people. Most supported the district, she said, but those who didn’t were “livid” about it.

“We knew our patients by their first names, I knew their histories as soon as they walked in the door,” said Candi Ratliff, former chief nursing officer. “This was a community hospital with a community heart.”

As the months wore on, things got ugly. Ratliff said several opponents told her that she “was only concerned about [her] job.” Smith said she was personally threatened and was called a “dog.” Pittman was stung by the anger leveled at her and her son. In response to a Facebook post from someone who wanted to see the hospital close down, Pittman shared her family’s story. For Cole, she wrote, being close to a hospital could mean the difference between life and death.

“I had a guy come back at me with, ‘Well how about I just buy you an oxygen tank and bring it to your house and then we can all save some money and not have a hospital,’” she remembers. “My feelings were really hurt.”

On election night, Pittman went to a high school volleyball game to distract herself. Her husband, Dustin, stayed home, texting with updates. If the tax district measure failed, her family would move. “We built a brand new house, and having to give that up because there’s no hospital, that’s hard to do,” she said. “Every time me and my husband would talk about it, it would make us more upset.”

[Hear former Bowie Memorial employees Amanda Thompson and Tessa Tibbs discuss losing their jobs at the hospital.]

In the hours before the vote, hospital respiratory director Tessa Tibbs’ stomach was in knots. She and her co-workers were confident that their campaign would be successful, but as the night wore on, she got a bad feeling. “I remember thinking several times, ‘This isn’t going to happen,’” she said. “I didn’t understand, and I think that [voters] truly didn’t believe that we were going to close. It didn’t matter what we said.”

When the ballots were counted, the hospital district measure failed by 184 votes. Tibbs remembers feeling like she’d been punched in the gut. Along with her husband and daughter, who also worked at the hospital, Tibbs would lose her job. Moreover, she said, she’d be losing her “work family” and a place that felt like home.

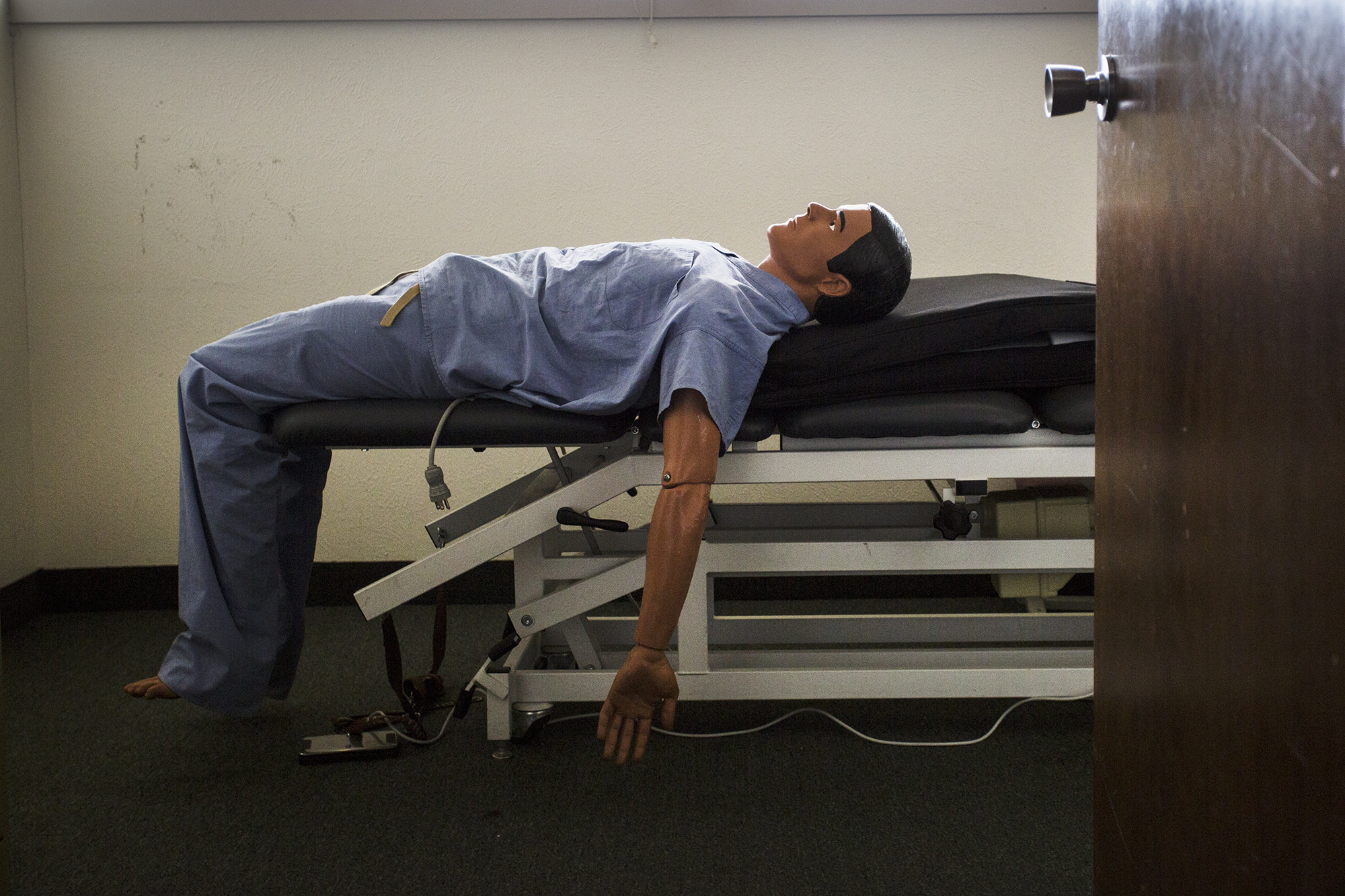

Bowie Memorial shuttered in November, and the fallout was immediate. There were 130 layoffs, a sizeable loss for a small town. The hospital had handled an average of 125 patients every week in the ER, and dozens more who came for rehabilitation services. Now patients would have to travel 20 or 30 miles to hospitals in Nocona or Decatur. The loss of hospital-related business also took a large bite out of sales tax revenue — a blow to a town already struggling with a downturn in the oil business. Within weeks, several houses near the hospital, including Pittman’s, went on the market.

Smith says she realized, even during the campaign, that patients might suffer and people could lose their jobs. “I know the hospital closure has hurt a lot of people, both financially and personally, and I do feel for them,” Smith said. “But it was really the only way that we are going to end up with something better.”

Two months after Bowie Memorial closed, when I visited the town in late January, emotions were still running high. Former employees cried as they talked about losing Bowie Memorial, and many who lost their jobs still hadn’t found work.

Former patients, including one couple in their 70s and the mother of a boy with cerebral palsy, told me they considered moving. The rifts created by the vitriolic campaign still hadn’t mended. Residents told me that former friends avoid one another at Wal-Mart and the bank, and families remain divided.

Bowie Mayor Larry Slack, a retired businessman who took office last year, said the city lost $300,000 in sales tax revenue in the four months after the closure. He also worried that businesses would leave. “There is no free lunch,” Slack said after the vote.

[Hear Mayor Larry Slack discuss the strain losing the hospital has put on Bowie’s ambulance services.]

According to Slack and several hospital employees, many opponents of the tax district had come to regret their vote. But no one would speak on the record. Crystal Prince, the main architect of the campaign against the hospital district, also declined an interview, telling the Observer that she preferred to “move on.”

“They didn’t believe it was going to close,” Slack said. Among them was Laurie Lambeth. “I am hearing a lot of people say they want the hospital, and that they were misled,” she wrote to the mayor. “Could I go around town and collect signatures from people who want to change their mind?”

“You can’t change votes,” he said. “It’s done.”

But Smith stands by the anti-tax campaign. People can get to Nocona or Decatur on their own, she contends, or paramedics can handle emergency needs on the ride. She points out that Bowie residents can go to Bowie’s United Clinic of North Texas or get rehab services in town.

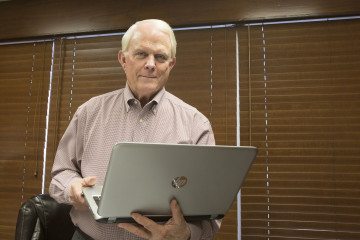

Not quite, according to Dr. Gary Evans, who owns the clinic and was a physician at the hospital. In the 34 years since he opened the clinic, Evans said, his physicians have used the hospital to perform surgery, and they referred patients there for other

services. The notion that the clinic can provide the same services is “naive,” he said.

“Hospitals are for more severely ill patients; it’s where you do surgery, diagnostic tests, things like that,” he said. “You can’t do that in a clinic, so it’s quite a bit different.”

Now, Evans sends patients out of town for scans and lab work. The closure has also financially damaged the clinic, which was already struggling because of stingier reimbursements for Medicaid and Medicare patients. Without revenue from surgeries performed at the hospital, Evans said, he has laid off two workers and predicts he’ll have to let more go. “It’s naive to think it’s not going to affect the community,” he said. “It already has.”

The loss was “heartbreaking” for Heller, who served as hospital administrator three times over 40 years. “This whole deal was just a needless tragedy,” he said. “It’s like a death in the family, with all these employees…. You just don’t replace those people overnight.”

In the weeks after the closure, Heller and the hospital board sold some of the facility’s assets and searched for a buyer to purchase and reopen it. Several bids, many from smaller, for-profit companies, fell through. Bowie is not alone in struggling to find a business model for its hospital. Of the 13 Texas rural hospitals that have closed since 2010, seven remain closed; three have reopened with the same level of care; and another three have reopened with only emergency or urgent care services, according to University of North Carolina researchers.

A mid-February deadline was set for final proposals to buy Bowie Memorial. The lone bid came from Dr. Hasan Hashmi and his son, Faraz, who run Texas General Hospital in Grand Saline near Tyler, a facility notorious for charging rates well above industry

norms. In a 2015 report by researchers at Johns Hopkins University, Texas General was ranked No. 11 on a list of the 50 worst “price gougers” in the country. Those 50 hospitals charge patients an average of 10 times the price allowed by Medicare.

In late February, the hospital board accepted the Hashmis’ $1.5 million bid. It was the last chance to save the hospital and they felt they had to take it. In an interview with the Observer, Faraz Hashmi said he and his father plan to reopen Bowie Memorial in the coming months. Like Texas General, the hospital will accept Medicaid and Medicare patients and offer a financial assistance program for patients who qualify, he said. But charging high rates to privately insured patients gives rural hospitals the best chance to survive financially, he said.

“Trends are showing that the cost of providing health care is increasing, and the reimbursements rates are going down,” Faraz said.

Faraz said the hospital will treat anyone who shows up at its ER, regardless of ability to pay, as required by federal law. “We’ll take care of [patients] to the best of our ability. We won’t look at whether they can pay, or their insurance,” he said. But “to keep that philosophy of health care alive, you have to make that work financially. We will make sure that whatever we do is legal and is fair.”

Otherwise, hospital officials would have had to sell the building and file for bankruptcy. Although Evans says he understands the hospital board’s tough position, he’s wary. “We’re kind of concerned that [the deal] might turn into a problem for the local people,” he said. “They may be forced to go to the ER and have a procedure that’s not going to be covered very well by their insurance. But we’re open to the idea of working with them, should they have a commitment to the community.”

Five months after the closure, Pittman’s house is still on the market. Before the deal was made to reopen the hospital, she and her husband had already decided to leave Bowie. The months of uncertainty and infighting left Pittman with a bad taste in her mouth.

“I love our town, and I know there’s good people here,” she said. “But it really bothered me that the community would not support the hospital.”