The Draw of Death Row

With “dark tourism” on the rise, Huntsville’s prison museum is thriving.

With “dark tourism” on the rise, Huntsville’s prison museum is thriving.

by Robyn Ross

April 18, 2016

The three syringes lie in a row, lined up neatly on a somber black background. Displayed with a saline drip bag and looping IV catheter, the vials are oversized, as though designed for the chubby hands of a child playing a macabre game of doctor. Below each is a typed card explaining its purpose in the December 1982 death of Charlie Brooks, Jr., the first person in the United States executed by lethal injection:

“Used to administer Sodium Thiopental which sedated the inmate.

Used to administer Pancuronium Bromide which collapsed the inmate’s diaphragm and lungs.

Used to administer Potassium Chloride which caused the inmate’s heart to stop.”

To their right is a pair of hair clippers used for shaving inmates’ heads before electrocution as well as a sponge that was soaked in salt water to conduct electricity. The last thing to touch dozens of men’s shaven skulls, the sponge sits on a plastic riser, its face pale and pockmarked like the surface of a distant moon. A second sponge is in a baggie on a shelf a few steps away in the Texas Prison Museum’s vault. The objects sit there matter of factly, their subtle presentation belying the roles they’ve played in execution, Texas history and making Huntsville — with its five prisons and the headquarters for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) — shorthand for the death penalty all over the world. it’s difficult to believe that the very sponge used in the death chamber is now on display in a one-story building just off interstate 45.

“Well, where else would it be?” curator of collections Sandy Rogers asks rhetorically.

Except for the official papers at the State Archives in Austin, most memorabilia from the Texas corrections system reside in Huntsville’s red-brick Texas Prison Museum. A manikin waves to visitors from the faux guard tower near the door. Inside, a single large room tells the story of the prison system’s history — or at least a selectively edited one.

The roadside museum is the most comprehensive education many Texans, and other travelers, will get on the state’s corrections system. Although the museum’s small budget and close connection to the prison administration have limited its scope, it has an unmatched opportunity to convene conversations about crime, punishment and justice, especially given the expanding ranks of its guests.

For a dollar per person, visitors can borrow striped shirts and snap selfies behind bars.

From the Tower of London to Alcatraz Island, old prison sites have long been big tourist attractions. But in the United States, the late-20th-century replacement of crumbling buildings by more modern facilities has led to a proliferation of new museums in old jails. And attendance at such sites — sometimes called “dark tourism” — is increasing, perhaps partly as a result of television shows about prison life. Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia last year counted nearly 213,000 visitors, quadruple the number it had a decade ago. Even in out-of-the-way Mansfield, Ohio, and Moundsville, West Virginia, visits to the local prison museum are tracking steadily upward. Instead of a single historic building, the Texas Prison Museum showcases the artifacts of a prison system, but its popularity also is increasing. “When it first opened, I thought, ‘Who in the world would want to go to a prison museum?’” says director Jim Willett, 66, a soft-spoken retired warden. “But I can’t imagine us having a more varied group of people come here — we get anybody from attorneys to ex-inmates.”

Last year’s visitors came from all over the world. They arrived alone, with their kids on vacation, on school field trips, on charter buses loaded with senior citizens, with their motorcycle clubs, and on the way to visit spouses on death row. Some showed their prison ID cards, mentioned where they’d been incarcerated and cracked jokes about former residents getting discounted admission.

Most spent between 45 minutes and an hour looking at artifacts and presentations, among them a pistol that belonged to Bonnie and Clyde, the display about the annual prison rodeo with inmate cowboys, and Old Sparky, the electric chair that ended the lives of 361 men between 1924 and 1964.

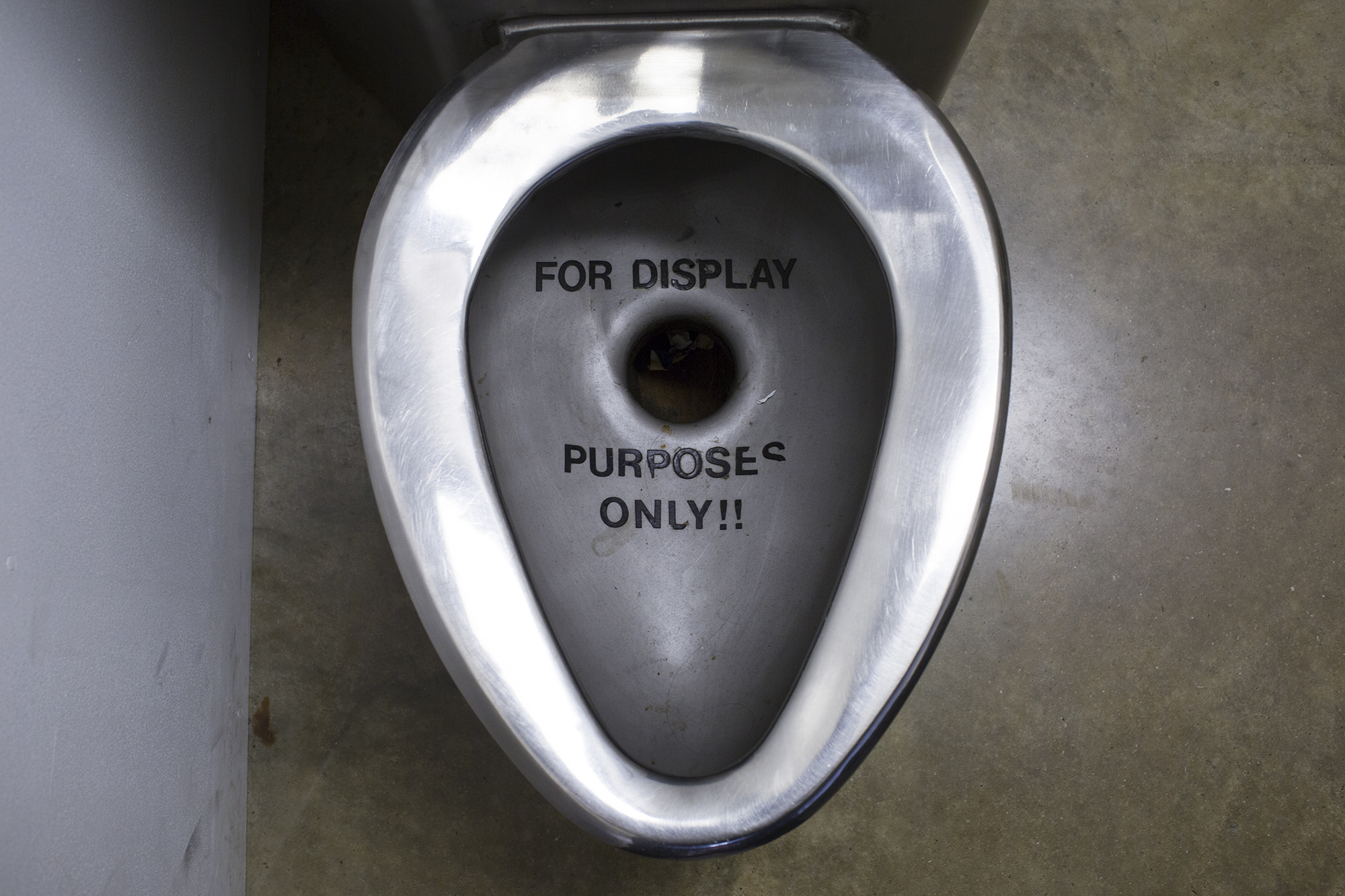

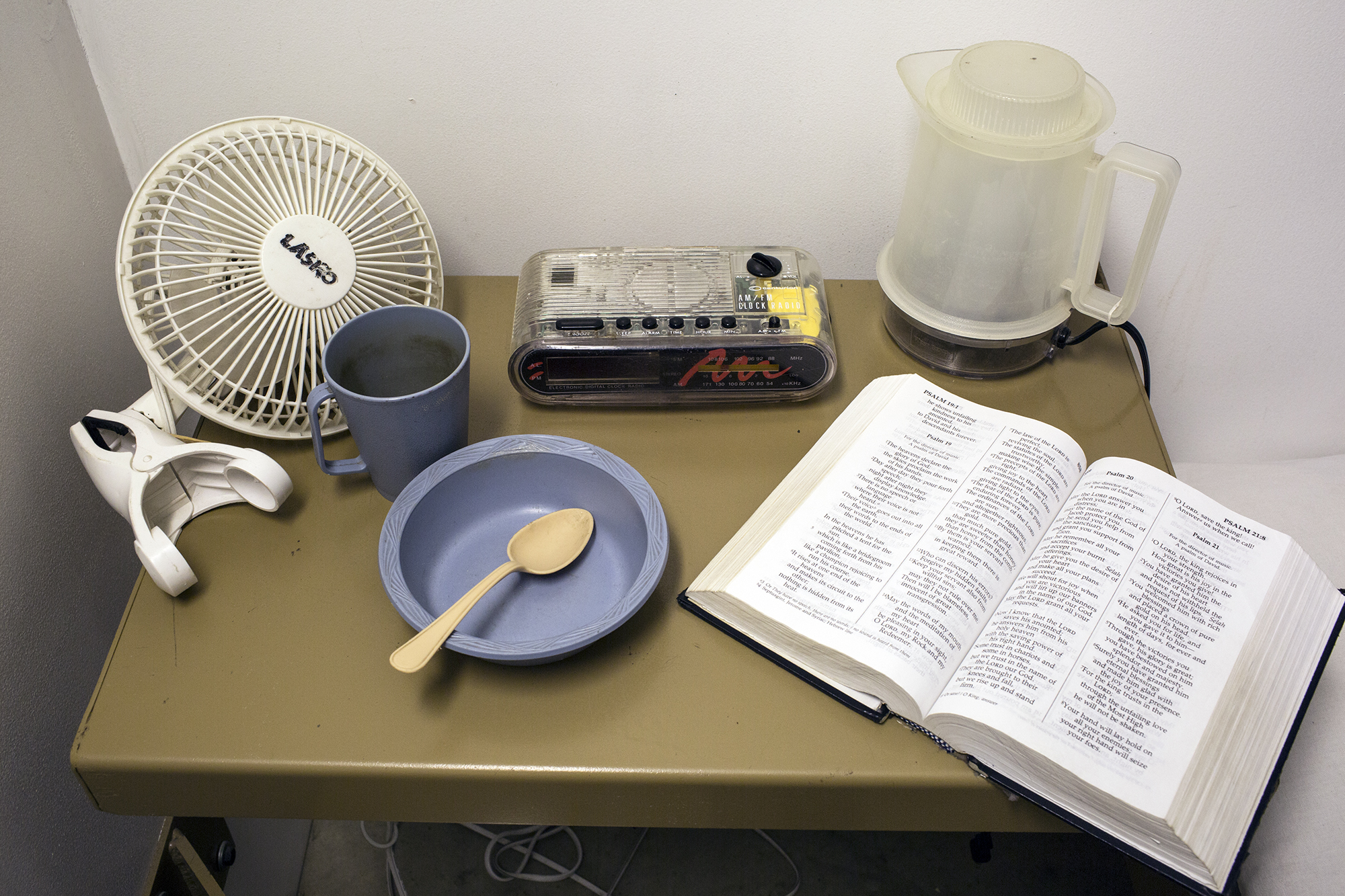

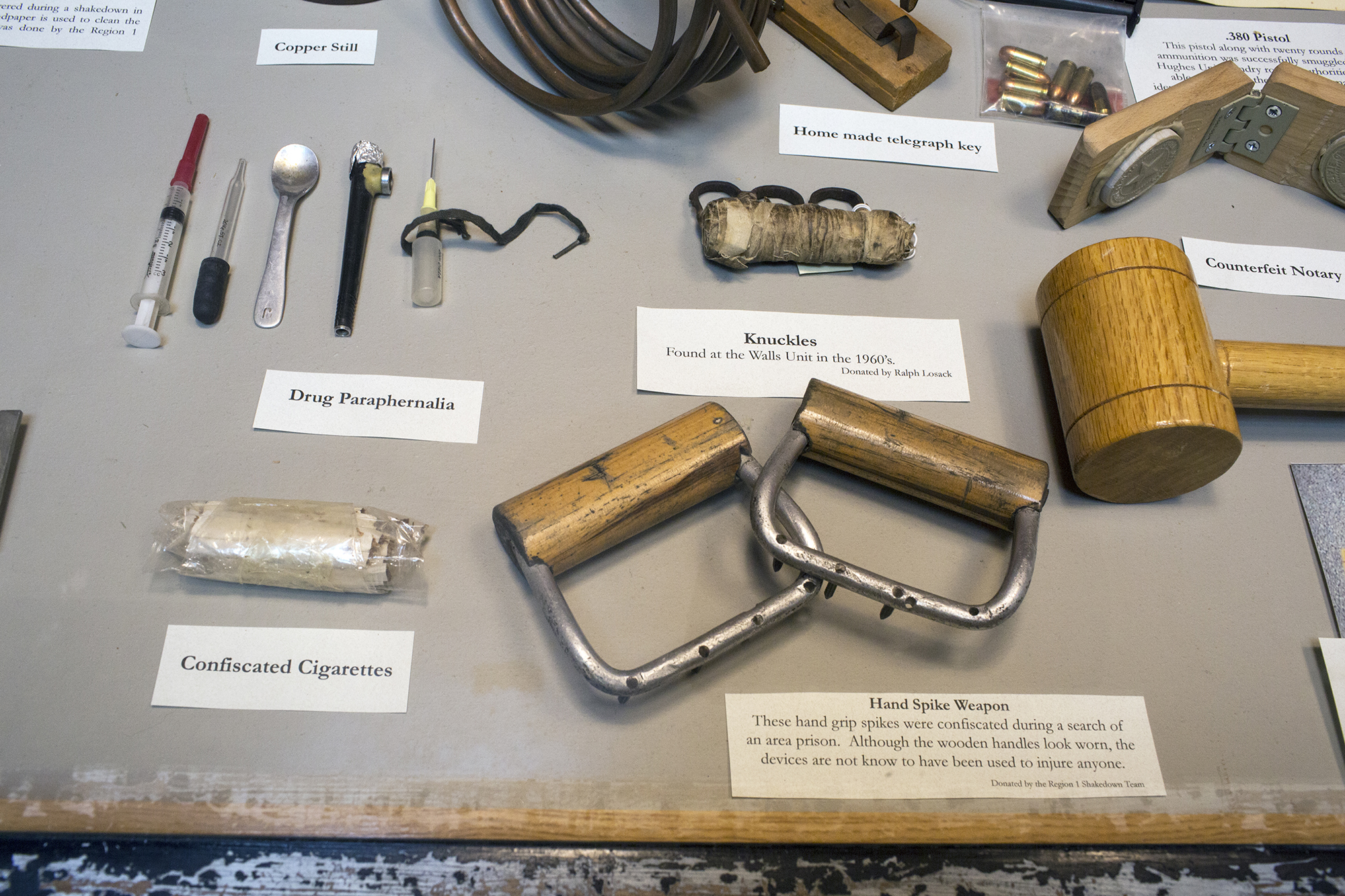

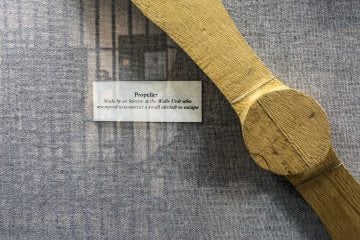

People like to play outlaw, walking into the replica of a cell, and for a dollar per person, visitors can borrow striped shirts and snap selfies behind bars. Some parents appreciate the chance to shut their kids in the cell for a moment of deterrent contemplation. The contraband case displays prohibited items made by inmates: a knife concealed in a flip-flop, a Coke can with a secret compartment, a jump rope made from state-issued boxer underwear. Nearby, the art display shows what else inmates create with time and limited materials: a jewelry box and cross made from matches, a rosary made from pencils, a hand-drawn game of “Prisonopoly,” patterned after a Monopoly board with real estate named for Texas prison units.

“I’m struck by the talent of the prisoners,” said Shannon Pettus, a bank sales representative from Conroe, who visited in February. “It makes you wonder, is it something they knew that they had going in? Or was it something they tapped into because they were in a situation where there was nothing else to do?”

The objects sit there, matter of factly, their subtle presentation belying the roles they’ve played in execution, Texas history and making Huntsville shorthand for the death penalty.

The museum “has to do with part of life we don’t get to see,” Gomez said. “And these guys that are in there get very creative when they have 40 years to think about what they did.”

That creativity is visible in crafts sold in the museum’s gift shop, which purchases curios made by inmates and sells them at a markup. The $25 nickel key chains, some reading “Death Row,” are popular. The shop also sells T-shirts — one with an image of the electric chair that reads “Home of Old Sparky.” Old Sparky shot glasses go for $4, a box of “Solitary ConfineMiNTS” for $2. A decade ago, under a previous director, the shop sold ballpoint pens crafted to look like injection needles. After a visitor complained, they were discontinued.

Gift shop sales ($250,000 last year) help support the museum, which receives no state funding — a fact announced in block letters on the front door. Nor is it officially connected to the prison system. it was the brainchild of TDCJ administrators, though, and that has shaped the story the museum tells.

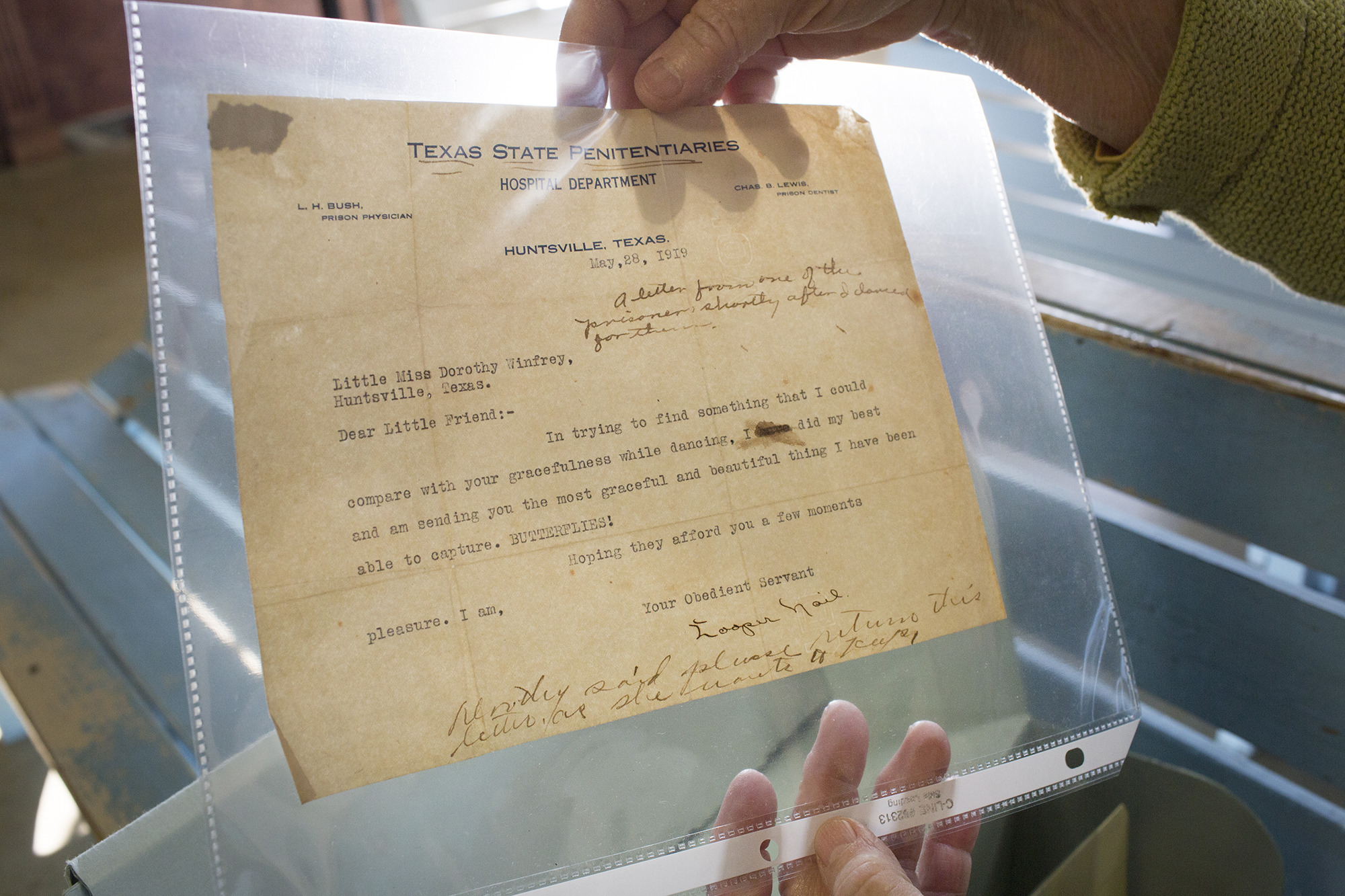

In the mid-1980s, officials in what was then called the Texas Department of Corrections (TDC) discussed starting an archive to preserve the department’s history. Meanwhile, Huntsville’s leaders were deciding how to commemorate the Texas sesquicentennial in 1986. When Robert Pierce, a folklorist and oral historian who taught in the prison system and at Sam Houston State University (SHSU), heard about the archive, he volunteered to run it. Pierce secured permission to photograph and interview anyone in the system — inmates, guards, the electrician who maintained Old Sparky. “You start people talking about their lives, and that’s where the stories come from,” he says.

Ken Johnson, then an administrator for the system, was appointed Pierce’s liaison. Together they collected filing cabinets full of documents, interviews, photographs, VHS tapes. Johnson suggested turning the archive into a museum, and a group of leaders in TDC, SHSU and the Huntsville community formed a nonprofit to raise money.

”When it first opened, I thought, ‘Who in the world would want to go to a prison museum?’But I can’t imagine us having a more varied group of people come here — we get anybody from attorneys to ex-inmates.’”

But TDCJ and SHSU keep the Huntsville economy stable, says Jane Monday, who served as mayor from 1985 to 1991 and was part of the planning effort. “TDC has always been appreciated because their administrators and many of their employees live here and work here; their kids go to school here; they’re part of our churches and organizations,” she said. “The museum was simply a move to celebrate that heritage that’s been here and underwritten us for so many years.”

In 1989 the museum secured a location: an old bank building that had been sitting empty on Huntsville’s courthouse square. Its two vaults were perfect for displaying the big-ticket items on loan from the state. One housed the weapons; the other became a simulated death chamber displaying Old Sparky. “People want to sit in it, they want to carve their initials in it,” Pierce remembers. “We had trouble with people wanting to take their picture in the chair.”

The museum was assembled by a corps of community volunteers using donated materials.

“I was down there in my blue jeans trying to figure out how to hang stuff and label it,” Monday recalls.

Pierce, Johnson and a colleague, photographer Jim Balzaretti, assembled the original exhibits. “We knew we’d have the guns, because that’s always a draw — because we’re thinking tourism, right? — to bring people in,” Pierce remembers. “And the chair. But I said we need to have artwork in there, and we need something about the [prison] education system. It can’t be all just security and blood and guts.”

Today, museum visitors start by watching a short video about the Texas prison system and improvements — like offering education and job training — it has made over the years. Many prison museums offer similar narratives about a corrections system’s evolution, says Rutgers sociologist Michael Welch. Author of the 2015 Escape to Prison: Penal Tourism and the Pull of Punishment, Welch says that prison museums attempt “education, enlightenment and a sense of history. … They generally walk up through time, showing early forms of punishment with an emphasis on corporal punishment and the death penalty, and in many cases that we’ve moved beyond that to more humane forms of intervention.”

But while the museum may reinforce a message of humane treatment as progress, it also reflects prison administration to the exclusion of inmates, says Elizabeth Neucere, a history master’s graduate from SHSU who wrote her thesis about the museum. While panels throughout the museum explain the work inmates do, few exhibits feature prisoners’ voices. Most inmates mentioned by name were executed, tried to escape, or were considered “famous and infamous.” A photo exhibit featuring executed inmates is one of the few displays that allows visitors to hear the voices behind the bars.

“The Texas Prison Museum … inhibits the possibility for public forum by creating silences in its historical presentation through the active choices made in exhibit design or display that makes a narrative superficial or absent,” Neucere writes in her thesis. “Impropriety in the Texas prison system goes unnoticed by museum visitors, making contemporary inmate battles for human rights seem unwarranted.”

For instance, Neucere says, the exhibit on inmate punishment displays handcuffs, a ball and chain, and old padlocks, as well as the bat, a leather strap with a wooden handle legally used to whip inmates until 1941. The card next to the bat says “Used for corporal punishment on convicts until the mid 1940s,” omitting the 1909 state investigation that uncovered abusive use of the bat, debates about banning it during the 1912 governor’s race, and its temporary replacement with the “dark cell,” an early form of solitary confinement. The bat returned to widespread use in the 1930s before being banned in 1941. But none of this information is present in the display.

The museum’s selective silences, Neucere says, are partly a response to Ruiz v. Estelle, which resulted in federal oversight and major reforms to the prison system after the 1980 ruling that it was unconstitutional. “Ruiz is not remembered fondly among the prison system and this is reflected in the museum, along with any other court case against the system,” Neucere writes. The plaintiffs’ accounts of overcrowding, inmate-on-inmate violence and inadequate medical care brought negative publicity. She suggests that, consciously or not, the case likely influenced the museum founders’ presentation of the story.

Pierce, the volunteer archivist, says there’s probably some truth in that argument. Many people who helped with the museum were directly involved with Ruiz compliance issues, “and they were preoccupied with people being sued and fired,” he says. “I think the thing they liked about the museum is that it gives a sense of authenticity, history and importance: ‘Yeah, I worked at the prison system, and there were some bad things about it sometimes, but we have a history.’”

Asked if he thought some of the decade-old informational panels should be updated, Willett, the museum director and retired warden, was hesitant. “History doesn’t change, so a lot of what’s out there is, in my mind, never going to be updated other than to just refresh it from the fading,” he said. “Some of the stuff is historical, and it’s over with, and it won’t be changed.”

But interpretation of history does change, and Neucere, who interned at the museum before being hired as assistant curator of collections, is updating the display about inmate punishment; when Rogers retires at the end of this year, Neucere, 25, will take over as curator. Willett has approved adding an interpretive panel about inmate punishment from the 1800s to the present, and another about the bat. Neucere is organizing a speaker series with SHSU faculty and former guards and inmates. The project, patterned after a series at Eastern State Penitentiary, will reflect new information and multiple points of view.

In the last decade, “museums have been moving away from the whole detached, ‘here are some objects on display, this is what happened,’ providing only one master narrative,” Neucere says. “Now museums are trying to present multiple narratives and engage with multiple stakeholders and have dialogue with visitors.”

At Eastern State Penitentiary, the Big Graph exhibit asks visitors to reflect on mass incarceration. The 16-foot-tall, three-dimensional outdoor graph comprises one bar per decade of American history. Each bar’s height represents the number of people in prison, and the bars are color-coded by race. Every visitor who takes an audio tour is prompted to decide what the bar representing 2020 should look like. “The core of our mission these days is to ask people to reflect on this,” says Sean Kelley, the museum’s director of interpretation and public programming. “If there’s one takeaway from our entire tour, we want it to be that this [prison] system has been changing all along, and it continues to evolve, and these are human decisions.”

The Texas Prison Museum does not ask guests to reflect on current events or debate issues. But one can imagine the potential for encouraging dialogue among visitors who come from around the world to the city they associate with incarceration and the death penalty. “The Texas Prison Museum has the potential to become what is called a ‘post- museum,’” Neucere writes in her thesis. “This type of museum has developed out of the new museum theory and is one that actively tries to engage its visitors and stakeholders in discourse over difficult and controversial issues, rectify social disparity, and promote social cohesion.”

The museum has planned to add a wing for artifacts piling up in its vault and an off-site storage facility, but it doesn’t have the funds yet. What is certain is that more visitors are coming: A conference center for a law enforcement training program affiliated with SHSU is slated to be built on state land next to the museum, which all but guarantees traffic will increase.

When visitors arrive at the new center, they will see the view museum patrons have now — a horse pasture and the Holliday Unit prison across the interstate. On sunny days, the field turns a blinding silver-yellow. Brighter still are the roofs of the Holliday Unit, surrounded by guard towers and barbed wire. Inside are 435 employees, roughly 2,100 inmates and at least 2,500 stories. The closest most people will get to hearing them is a 45-minute stop at the museum to look at words on a panel and objects under glass.

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.