The Encyclopedic ‘Country Music USA’ Tells (Almost) the Whole Story

Laird does a masterful job of showing how, for many performers, the whole question of authenticity has become ridiculous.

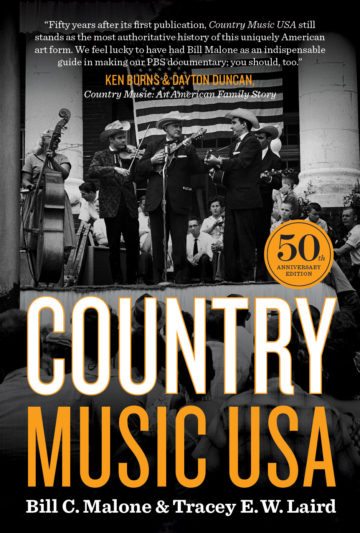

Country music historian Bill C. Malone has lived to see the 50th anniversary reissue of his landmark book, Country Music USA. Fellow scholar Tracey E. W. Laird (Austin City Limits: A History) joined him for this, the book’s fourth edition, to bring the story up to the present day.

By Bill C. Malone and Tracey E. W. Laird

University of Texas Press

$27.95; 768 pages

Country Music USA is an important book. It was the first to tell the genre’s complete story, beginning with its folk, religious and early commercial origins — the ballads of the British Isles, the tent revivals, the 19th-century minstrel shows and the 1927 recording session in Bristol, Tennessee, that saw both Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family make their first recordings. In the original edition Malone carried the story forward to the late 1960s, when giants of various twangs and stylings still walked the earth. (A few still do — just don’t look for them on commercial radio.)

Now Ken Burns is using the book as a guide for his next PBS documentary epic, Country Music: An American Family Story. So this is a good time to re-evaluate the book and think about what Malone did and didn’t accomplish.

For starters, the book is about as encyclopedic as a narrative can be. A chapter on “The Cowboy Image and Western Music” spends a very interesting and appropriate number of words on Gene Autry (more on him later), but at least seems to tell the stories of everyone who followed in his horse’s hoofprints. The general reader would indeed want to read about the Sons of the Pioneers, but may flip past the pages on Patsy Montana; the original Beverly Hillbillies, a musical group whose name was borrowed by the more famous TV show; or the Girls of the Golden West. On the other hand, it’s certainly good to have it all written down. Malone’s inclusiveness gave this reader a happy jolt when he drilled down to swing bandleader Adolph Hofner, who continuously played the South Texas dance halls I grew up around — I was rebuffed by Texas magazines when I tried to write about Hofner decades ago, and never expected to see his name in print.

The “all” includes absorbing passages on the multicultural origins of our most dyed-in-the-wool ’Murican art form. The connection between British folk and country music is widely understood, but Malone also shows how the steel guitar is an Hawaiian import and how Jimmie Rodgers’ yodels are rooted in 19th-century U.S. tours by Swiss singers.

Which brings us to the connection between black music, especially the blues but also jazz, and country. Here Malone may leave readers frustrated. He points out the connections numerous times, but never to the point of asking why country and Western music came to be considered white music. In a lengthy passage on Charley Pride, arguably the only black country superstar, he writes, “The black contributions to country music are too well known to warrant repetition here.” But when Malone writes about the social forces that shaped the country audience, he omits race. Collaborator Laird takes on race, and especially sexism, much more directly in her concluding chapter.

“What is ‘real’ country music? The question itself is worth mocking.”

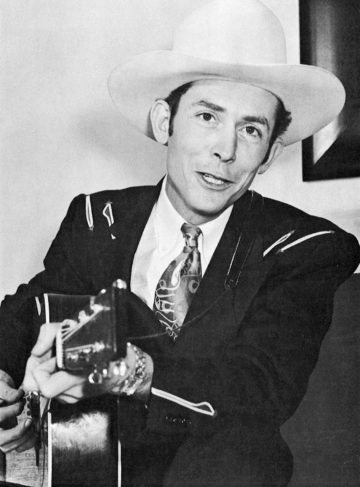

Perhaps it’s because the subject isn’t dealt with directly, or maybe it’s because we’re in the age of Black Lives Matter, but the unspoken story about race and country music haunts the narrative. Malone points out how black performers and “race records” greatly influenced country stars from Jimmie Rodgers to Hank Williams to Bill Monroe; like Williams, Monroe had a black mentor. Listening to the Jimmie Rodgers channel I requested on Pandora, I was struck again by how, except for the yodeling (admittedly, a pretty big “except”), the line between Rodgers’ country blues and that of black bluesmen was a fine one. In fact, Pandora quickly served Leadbelly on the Rodgers channel, making the comparison explicit. Malone shows that, in 1942, Billboard initiated its coverage of country music in a column titled “Western and Race,” which covered “Everyone from Tex Ritter to Louis Armstrong.”

Speaking of the blues, Malone’s passage on Gene Autry was an ear-opener. I’m as big a fan of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” as the next guy, but in general Autry’s crooning has always struck me as schmaltzy beyond repair. So it was a shock to read that, in imitation of Rodgers, Autry got his start as a yodeling bluesman. Don’t snicker until you hear his “Dallas County Jail Blues,” with its casual references to enjoying the blues you hear behind bars while you’re also fearing the electric chair. It sounds pretty authentic, whatever exactly that word means.

The question of what makes for “authentic” country music has survived the decades. Malone does a fine job of showing how this exact question resurfaces through the years, starting with Bob Wills’ shocking decision to employ a drummer on the stage of the Grand Ol’ Opry —a move that of course has its echo in the famously hostile reaction Bob Dylan got when he first plugged in his electric guitar, back when folk was supposed to be “authentic.”

When it comes to the music itself, the question of authenticity has long since been settled in the country mainstream. Mainstream country’s authenticity, such as it is, resides mainly in the feisty attitudes of the singers and perhaps in the drawl in their voices, and also in the more retro recordings of Brad Paisley and others. “While respecting the past in overt musical ways,” Laird writes, “Paisley avoids coming across as stuck in it.” But the slide guitar might as well have slid back to Hawaii, and fiddlers don’t work as much as they used to. Something like musical authenticity, in the sense of sounding like honky-tonk or swing, only resides in the margins, where you find such neo-hillbilly figures as Wayne Hancock and Dale Watson.

Along with examining the role of gender in the blacklisting of the Dixie Chicks, and of race in the Country Music Awards’ snubbing of Beyoncé’s “Daddy Lessons” in 2016, Laird does a masterful job of showing how, for many performers, the whole question of authenticity has become ridiculous. Authenticity was still in play in the 1990s, she writes, when “‘new’ versus ‘traditional’ was ‘segregated on country radio,’” and country artists in both camps needed the mainstream to reach an audience.

No longer. Here Laird quotes, approvingly, a No Depression review of a Wheeler Walker performance. Wheeler Walker is the pseudonym of comedian Ben Hoffman, and his debut album is the ironically titled “Redneck Shit.” “‘What is ‘real’ country music?’” the reviewer asks. “‘The question itself is worth mocking, and I actually think that’s what Walker’s doing.’”

Laird closes by writing that today no “media entity gets to decide what is and what is not country music. … No gatekeeper guards the center because there is no center.”

There’s only the music in all its variety and occasional glory.