The Extra-Lite Gov

How David Dewhurst diminished the state's most powerful office.

This story was corrected and updated on Nov. 4.

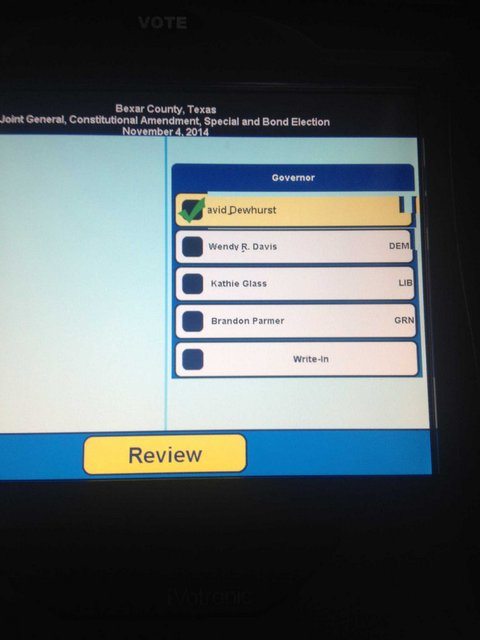

During the 2007 session of the Texas Legislature, Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst brought the Senate to near-mutiny. It was May 15, near the end of the session, the point at which bills usually come flying through the chamber. Instead, the Senate was tearing itself apart over House Bill 218, better known as the Voter ID Bill. Dewhurst had placed himself behind the bill. To many Republicans, it was an obvious measure, necessary to keep illegal immigrants from voting. As Dewhurst put it, you need an ID to “check out a library book,” so why not to vote? To Democrats, Voter ID was more about keeping poor, minority citizens from voting. The Senate broke into partisan camps, with every Republican supporting the measure and every Democrat opposing it. The Democrats had exactly enough votes—11—to keep it from passing.

Enough votes, that is, as long as all their senators were there. As president of the Senate, Dewhurst could bring bills to a vote whenever he chose. He called a vote on Voter ID while one Democrat, Carlos Uresti of San Antonio, was home with the flu and another, John Whitmire of Houston, was momentarily off the floor. When Whitmire came back, Dewhurst refused to count his vote.

On the grainy Senate video, you can hear a collective gasp rise from the floor. The Senate prides itself on being a sober, collegiate body, bound together by unwritten codes of honor and tradition. Senators might disagree on policy; they might attack each others’ bills; but at least in public, they treat each other with respect. By ramming through a contentious issue to a vote when members of the opposing party were absent, Dewhurst was stomping all over this tradition.

On the video, Dewhurst gradually loses it as Whitmire, with some bluster and profanity, insists that he voted and other senators support him. “Members,” Dewhurst admonishes, “I gaveled the vote. Senator Whitmire was not here. He did not vote.”

Rumbles erupt from the floor. Democrat after Democrat stands up to ask if, now that Whitmire is here, they can re-vote. Dewhurst, looking cornered, says he didn’t make the rules, he just follows them. Finally he gives in. “Members, sit down,” he yells, to little effect. “It’s not going to make any difference, but I’d be glad to do another roll-call vote.” He huffs audibly. He says to the agitated Whitmire, “You’re gonna compose yourself, or you’re gonna leave the floor.”

It wasn’t going to make any difference, Dewhurst was saying, because even if Whitmire was back, Uresti was still gone. Unbeknownest to Dewhurst, though, the very ill Uresti had come back during the scuffle to cast his vote. With his and Whitmire’s votes, HB 218 failed.

Dewhurst wasn’t done. The next morning, he issued a press release stating, “I can only conclude that the Senators who voted to block consideration of House Bill 218 did so not because it’s good public policy, but because they don’t believe in the basic American principle of one person, one vote.” As a final barb, Dewhurst accused Whitmire of having “ironically gamed the voting process by walking out of the Senate Chamber in an attempt to stall consideration of the Voter ID bill.”

This was a mistake. Dewhurst would later claim he hadn’t read the release—that an overzealous subordinate had dashed it off without authorization. (Dewhurst is on tape at the 2010 Texas GOP convention quoting from the release nearly verbatim.) According to the Quorum Report, an Austin-based political newsletter, the release episode was “the final straw” in Dewhurst’s problems with the Senate.

It wasn’t that Dewhurst had tried to pass a hard-right issue like Voter ID. It was how he had done it. By using tricks and poisonous press releases, Dewhurst had broken the most important unwritten rule in the Senate. According to one former senator, “you may dislike a member, you may argue with a member, but at the end of the day, you respect them.”

After Dewhurst’s Voter ID statement, senators considered removing him from the chair and running the Senate themselves. Three ranking senators, Republican Tommy Williams of The Woodlands, Democrat Leticia Van de Putte of San Antonio, and Republican Steve Ogden of Bryan, met with Dewhurst to tell him how precarious his situation was. For the rest of the session, the Senate ran itself. Dewhurst opened and closed sessions, but little else.

Dewhurst had entered office with great promise in 2003. His first term was a model of bipartisan leadership. One-on-one, he still has a reputation as a reasonable moderate. His overarching pattern as lieutenant governor, though, has been a series of blunders resembling his handling of Voter ID. His ambition has outstripped his political skill, as he has squandered power by angering senators in service of trivial, pandering issues. Eight years in, it is unclear what he wants or what he stands for beyond re-election.

He will probably succeed this year against Democrat Linda Chavez-Thompson, who hasn’t raised enough money to compete with Dewhurst’s personal wealth. It’s generally accepted in the Capitol that Dewhurst wants to move on to the governorship or the U.S. Senate. Meanwhile, Dewhurst has dragged the Senate through pointless bloodbaths and largely squandered the considerable power of his own office.

Dewhurst’s wealth allowed him to seek high office without decades of climbing the Republican political ladder. Dewhurst spent an unheard-of $8 million on his first bid for office in 1998, becoming land commissioner—an office that rarely costs candidates more than $1 million. Four years later, he would spend more than $9 million to beat former Comptroller John Sharp in the lieutenant governor’s race.

Some statewide elected officials stay in office a long time. Former Land Commissioner Garry Mauro, a Democrat, held office for 16 years before his failed run for governor; Democrat Bob Bullock was state comptroller for 16 years before moving to the lieutenant governorship. Dewhurst spent four years in the land office and went straight for lieutenant governor. Three years in, he started talking about a run for Republican Phil Gramm’s open U.S. Senate seat. (He ceded it to then-Attorney General John Cornyn). He has mused about the governorship, should Perry ever leave, and Republican Kay Bailey Hutchison’s Senate seat, should she retire.

“Bob Bullock came up through the system,” former Democratic Sen. Gonzalo Barrientos of Austin likes to say of the late, feared lieutenant governor. “Dewhurst came in through the clouds.”

Little is known about Dewhurst. His life story is an impenetrable fog of obfuscation punctuated by tantalizing facts. This secrecy has extended from his military record to the sources of his wealth to his current financial conflicts. He has repeatedly gotten into trouble with the Texas Ethics Commission for overly vague financial filings. State elected officials are required to either disclose their finances or put all their assets in a blind trust. Until 2008, Dewhurst declined to do either, putting his money in a (nonblind) trust and declining to release information about it.

We know Dewhurst wasn’t born into money—he grew up lower middle class in central Houston, raised by a widowed mother after his father died just after World War II. After graduating from the University of Arizona, he served in the Air Force, then spent three years as a CIA operative in Bolivia in the early 1970s. Citing national security, he has been quiet about his duties, though during his time there, the CIA reportedly provided intelligence and communication equipment to support Gen. Hugo Banzer’s bloody coup against leftist President Juan José Torres.

After he left the CIA, Dewhurst spent some time in the Office of State-Federal Relations in Washington before moving to Houston in time to get rich in the oil and gas boom of the mid-1980s. The prevailing story is that he found his way into a contract to build a cogeneration natural gas plant in Big Spring, Texas. In 1996 he sold the plant and two more, in Florida and upstate New York, for $226 million. No one has explained how Dewhurst, a man with no capital and few family connections, secured the money for a power plant.

It’s also unclear why Dewhurst entered politics. The question has been the focus of much baseless speculation. Dave McNeely, a veteran Austin journalist, recalls the first time a friend described Dewhurst, then in the land commissioner race, as “some rich Houstonian who made a lot of money and now wants people to like him.”

Whatever his reasons, Dewhurst’s money allowed him to run for high office as a political neophyte. He wasn’t necessarily unprepared: McNeely says Dewhurst had been preparing for some kind of run since at least the mid-’90s. (Dewhurst did not respond to several interview requests.) He had laid the groundwork through years of healthy donations to Republican women’s clubs, which circulated his name to people with influence and money.

“It sounds complicated, but it’s not,” says a lobbyist familiar with the clubs. “You just say, I’m David Dewhurst, I’m for fiscal conservatism, I’d like to sponsor your luncheon.”

Dewhurst also experimented with what became his trademark campaign strategy. First, he met privately with local leaders all over the state, gaining their support. During his campaign for land commissioner, he traveled to 107 cities, meeting local Republican leaders and gathering their support. This was the linchpin of his strategy—focus more on winning over local politicians and kingmakers than on selling himself to the public. Then he’d buy advertising to spread some textbook conservative message. In 1998 he pledged to trim fat from the land commissioner’s budget and secure money for public education. Finally, he poured on the money, burying his Republican primary opponent, state Sen. Jerry Patterson (now the land commissioner), and then his Democratic one, state Rep. Richard Raymond.

As land commissioner, Dewhurst gained a reputation as a competent, if not stellar, administrator. His successes were mixed. His office slashed its own budget (the actual amount they saved is in dispute), but it did so by firing more experienced, highly paid employees.

The few senators who worked with him then liked him. “I found him impressive,” says Carlos Truan, former Democratic senator from Corpus Christi. Truan was dean of the Senate when Dewhurst was land commissioner, and the two worked together on Veterans Commission bills. “He thought for himself, he was very smart, and he had a good command of the issues, both in veterans’ issues and land office business,” Truan says.

In retrospect, Dewhurst’s time in the land office was a prelude to his time as lieutenant governor. He was something of a caretaker, crusading for nothing but not messing anything up too badly, either.

When redistricting came in 2001, Land Commissioner Dewhurst was part of the five-member Legislative Redistricting Board. According to Truan, Dewhurst pledged to support a redistricting plan favored by Democrats and many moderate Republicans. He then reneged. Senators were enraged. Two Republican senators, Jane Nelson of Flower Mound and Chris Harris of Arlington, had to sell their houses and move to remain in their districts.

It’s not clear why Dewhurst switched positions. The plan he eventually voted for was sponsored by most of the right wing of the Republican Party. “I guess Dewhurst was more interested in his political future in the Republican party,” Truan says.

Since you never know who’s on your side until the final vote, oral agreements are paramount in the Senate. By going back on his word, Dewhurst cast doubts on whether his word was good. Though little publicized, the incident cast a cloud over Dewhurst’s run for lieutenant governor. The Texas Association of Business, a solid Republican redoubt, supported Dewhurst’s Democratic opponent John Sharp. So did many senators, both Republican and Democratic. During the 2002 campaign, one prominent Democratic House member told the Observer that “there are a lot of people looking forward to screwing with Dewhurst if he wins. You are going to have to stand in line to pop him.”

Dewhurst won, setting up another theme: He might be bad at interacting with the Senate, he might not have a clear agenda, but he is good at getting himself elected. Dewhurst beat Sharp handily, 51 to 46 percent. Dewhurst’s abilities as a campaigner would outstrip his ability to govern, though.

If Dewhurst’s rise to the most powerful elected office in Texas was meteoric, it also marked him as the first lieutenant governor in living memory with no experience in the Legislature.

Most other lieutenant governors had spent decades working in and around the Legislature before being elected presiding officer. Republican Bill Ratliff had spent 10 years as a state senator. Rick Perry had served three terms in the Texas House and two as agriculture commissioner. Bob Bullock was secretary of state for three and comptroller for 16. Democrat Bill Hobby hadn’t held office before becoming lieutenant governor, but he had grown up in a family synonymous with Texas politics. He also spent the years before his run for lieutenant governor working around the Senate, serving as parliamentarian and later chairing the Senate Interim Committee on Welfare Reform.

Dewhurst had spent four years in elected office and little time at the Legislature. Beyond special occasions like redistricting, the land commissioner interacts little with lawmakers except to, as one journalist puts it, “beg them for money.”

For the lieutenant governor, knowledge of tradition and a track record aren’t separate from power—they are power. Nearly all the office’s powers are granted informally by tradition. All the Texas Constitution says about the lieutenant governor is that “he shall preside over the Senate.” Over the years, this has become codified in the Senate rules into a fearsome arsenal of powers. As lieutenant governor, Dewhurst controls when bills come up to a vote. He controls which senators serve on which committees, as well as which of those committees gets assigned each bill. He can ensure that bills he likes are slipped to allies in committees certain to approve them. Bills he doesn’t support can disappear into committees that will ensure they die quietly.

These powers require knowledge of the Senate’s arcane, often-bizarre rules and traditions. For lieutenant governors to accomplish their agendas, they need the trust and support of the Senate.

“For a lieutenant governor,” McNeely says, “longevity leads to power because you get to spread more of your people around Austin. After a while, people coming in want to be on your team so they don’t end up as chair of the Lawn Care Committee.”

The prime example of an experienced operator would be Bullock, who during his 16 years as state comptroller trained a generation of some of Texas’ brightest political minds. As they filtered out of the comptroller’s office, his network grew. In 1997 Austin Chronicle writer Robert Bryce, musing on the sources of Bullock’s power, wrote that “his most important, yet least recognized, source of authority is the allegiance of dozens of former employees, who now work at all levels of government and the private sector. His former staffers seem omnipresent, many directing state agencies or wielding influence as lobbyists, lawyers, and consultants.”

Dewhurst didn’t have those connections. His about-face on redistricting had convinced a lot of senators they couldn’t rely on him.

Dewhurst initially rallied enough to dislodge some doubts. He compensated for his inexperience by hiring legislative insider and former Bullock chief of staff Bruce Gibson as his chief of staff and personal guru. During the 2003 session, he kept the Senate moving well. He kept the chamber clear of that session’s notorious redistricting battle, which was tearing the House apart, and shepherded through a school-finance bill. Dewhurst proved to be an adept, bipartisan consensus builder—so much so that Texas Monthly put him on its “10 Best Legislators” list despite the magazine’s practice of excluding presiding officers. In the accompanying text, titled “Leader,” the Monthly wrote that Dewhurst “was the unlikely hero of the session. He put the state’s needs ahead of an ideological agenda. He took the moral high ground and held it. That’s what being a leader is all about.”

In the special session afterward, Dewhurst repeated his about-face from 2001. He threw himself behind DeLay’s unusual mid-decade congressional redistricting plan, which Democrats saw as a cynical attempt to disenfranchise them. Like Voter ID would in 2007, the debate broke down along partisan lines. Under the Senate’s tradition requiring a two-thirds majority, it had no chance of passing.

Like most Senate “rules,” the two-thirds rule is a gentleman’s agreement with a long history. The rule emphasizes consensus-building and has helped to keep the Senate clear of the partisan bloodletting that often derails the House. The two-thirds rule is an example of the Senate’s tendency to favor compromise with one’s opponents over flattening them with a bare majority.

Perry had called the special session to pass the redistricting bill, but that was the extent of his power—he couldn’t force the Senate to pass anything. Had Dewhurst been a true moderate—as he had seemed to be six weeks earlier—he might have dismissed redistricting as a partisan issue not worth wrecking the Senate over. Had he been less ambitious, he might have accepted that he didn’t have the votes to pass redistricting and backed down. Instead, Dewhurst announced that “enough is enough.” He would suspend the two-thirds rule.

To both Democrats and Republicans, according to then-Sen. Barrientos, this was “pretty damn close to unforgivable,” and it was the worst mistake of Dewhurst’s career.

“The two-thirds rule is a rule that could benefit anyone: any political philosophy, any particular group,” Barrientos says. “One side one day, one side the other. They broke it—and for what? Just to screw the Democrats. It proved that he cared far more about partisan politics than the integrity of the Senate.”

The switch was so dramatic that Texas Monthly’s Patricia Kilday Hart published an extended mea culpa retracting Dewhurst’s spot on the best-legislator list and speculating that the moderate Dewhurst had been replaced by an evil, reactionary twin. Senate Democrats fled Austin for Albuquerque to deny the Senate the quorum needed to pass redistricting. Only Whitmire’s decision to break the boycott and return to Austin ended the six-week sojourn.

Dewhurst’s reputation never recovered. No matter what he said, no matter what he promised, he wouldn’t hesitate to tear the Senate apart for his own agenda.

What is that agenda? No one knows. He still has a reputation as a savvy businessman, and he has worked behind the scenes to help fellow senators push through progressive education and health bills. Judith Zaffirini, the Democratic senator from Laredo, says that on several occasions, Dewhurst helped her pass health care reform measures. In 2005, after her bill to fund AIDS medication for 20,000 Texans failed in subcommittee, she went to Dewhurst.

“I told him that AIDS was no longer a terminal disease, and that if this funding passed, thousands of Texans would live, work and pay their taxes,” she says. “If not, they will die, and we’ll have to pay for them in hospitals.”

Dewhurst, Zaffirini says, spoke to the Finance Committee chair. She credits him with the bill’s passage. “I didn’t agree with everything he did,” she says, “but if you could convince him on an issue, he would really go to bat for you.”

According to Kip Averitt, former Republican senator from Waco, Dewhurst brought new insight to the Senate, broadening the body’s thinking beyond the day to day. “He has a different outlook on certain issues than the extreme right,” Averitt says. “He’s very pragmatic. He always stacks costs against benefits.”

These accounts stand in contrast to the issues he burned many bridges to pass. In his attempts to pass Voter ID in 2007 and 2009, Dewhurst tried to bypass the two-thirds rule, nearly derailing the 2009 session. In 2011, Republicans will try again to pass it.

Dewhurst has supported mandatory ultrasounds for women seeking abortions. He proposed requiring every high school athlete to undergo steroid testing. He proposed to fingerprint 300,000-plus teachers in Texas just in case. Both proposals passed as part of the 2006 school finance bill. Four years later, after spending millions, the TEA reportedly has caught only about 20 steroid users.

“Dewhurst was a different kind of authoritarian than Bullock,” says Barrientos, “but he was authoritarian. He just wasn’t as good at it. He was strictly partisan, even though he tried not to appear partisan. He didn’t look like a right-winger, he didn’t act like it, but he supported everything right-wing I can remember.”

The crowning example of his devotion to the trivial was his 2007 support for his version of what his website terms “one of the toughest Jessica’s Laws in the country,” a ghoulish piece of legislation named after a murdered 9-year-old that would empower judges to give child-rapists the death penalty. On his website, Dewhurst’s campaign team names Jessica’s Law as one of his greatest achievements, an example of Dewhurst’s ongoing commitment to “public safety.”

According to a Capitol insider who worked on the issue, it was commonly known that “if you wanted to grab ahold of the electorate, you just had to find out how to guarantee the death penalty for child sex offenders.” The bill Dewhurst and his senior adviser Kevin Moomaw put together was so bad that Republicans talked its authors into taking it back to committee.

Dewhurst is smart, even a bit nerdy—a good listener, everyone agrees, and a moderate at heart. But for whatever reason, he has broken with tradition and used the Senate for his own political purposes.

Since the Tea Party insurgency started blowing holes in the Republican establishment, Dewhurst’s talking points have begun to resemble Tea Party talking points. He has campaigned on tough border security, warning about “spillover” violence from Mexico. He told an audience at the state GOP convention that “Phoenix, Arizona, has the second highest number of kidnappings in the world, right after Mexico City.” (The Austin-American Statesman’s PolitiFact, which evaluates politicians’ statements, concluded the statement was “false.”)

Dewhurst’s political showboating has worked. As Perry found himself under surprise attack in this year’s primary from Tea Party-backed challenger Debra Medina, Dewhurst sailed unopposed into his party’s nomination. According to early polling, he will easily beat Democratic challenger Chavez-Thompson.

“There’s a difference between a politician and a public servant,” says Barrientos, the former senator. “A public servant does what is right, what is necessary, despite the heat. He doesn’t please people short-term just so they’ll re-elect him.

“Dewhurst is a politician.”

update: Our account of the 2007 Voter ID controversy in the state Senate originally identified Sen. Mario Gallegos as the Democrat who returned to the chamber, ill, to cast a deciding vote against the measure. The senator who returned to vote was Carlos Uresti of San Antonio. The Observer regrets the error.