–

In July 2008, the U.S. Department of Justice shelled out $12,000 for a 1.71-acre strip of land along the Rio Grande’s north bank in the Texas border town of Roma. Designated RGC-1066, the property lay below a towering sandstone bluff offering a striking view of the Mexican city of Miguel Alemán. Sixty feet wide, the tract consisted of a short caliche road and a craggy riverbank overgrown with carrizo cane and mesquite. There, the Bush administration planned to build an 18-foot-high steel fence, part of roughly 700 miles of border wall that Congress had mandated. The wall, however, would never be in built in Roma, or anywhere else in Starr County: Federal engineers in both the U.S. and Mexican governments blocked the project, saying it would worsen flooding in an already flood-prone area. It was no idle speculation.

Over the course of three days in the summer of 2010, Hurricane Alex dumped more than two feet of rain on Northeast Mexico, overwhelming reservoirs and prompting dam releases along the Rio Grande. In Roma, floodwaters swallowed RGC-1066, climbing some 15 feet up the bluff. Had the fence been built, it would have been nearly submerged and might have washed away. When the floodwaters receded, much of RGC-1066 had simply vanished downstream. Elsewhere in the county, the same thing occurred: Land seized by the government was seized by the river. At a recent federal court hearing, a DOJ attorney put the matter thusly: “A lot of this land is not here anymore — so our take is someplace in the Gulf of Mexico.”

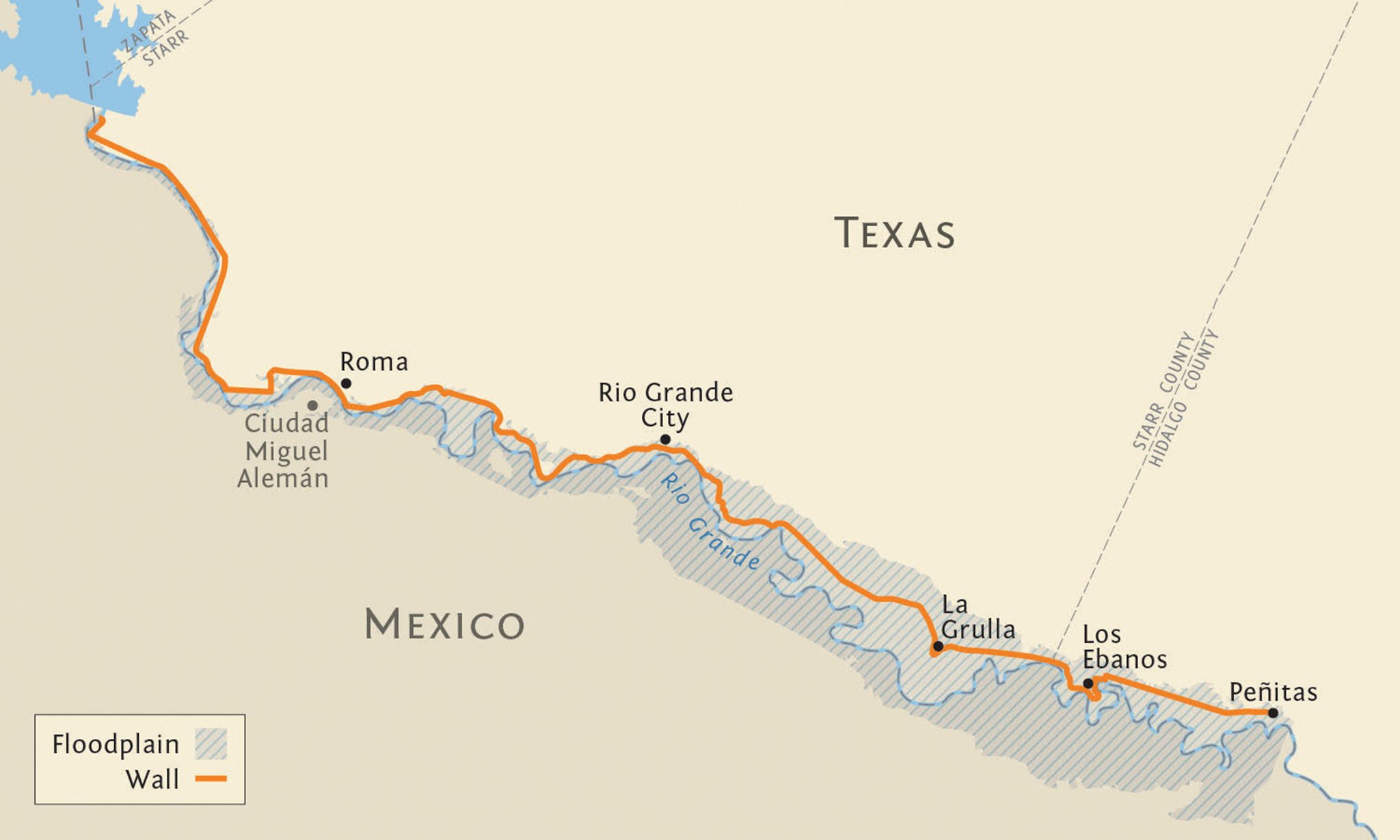

Today, despite the lesson imparted in 2010, the Trump administration has revived the dream of walling off flood-prone Starr County. In all, the administration hopes to run 63 miles of wall from Starr’s western edge into far-western Hidalgo County, downriver. Much of the barrier would slice through the Rio Grande floodplain. Trump also plans to super-size his wall, adding a 150-foot “enforcement zone,” a clear-cut corridor containing a Border Patrol road, electronic sensors, cameras and floodlights. (Customs and Border Protection has not addressed how that technology might fare underwater.) The plan means the government will soon seize new, wider swaths of property almost exactly where the river swallowed RGC-1066 nine years ago — a proposal that South Texas landowners and border-wall opponents view as reckless and absurd.

“They’re not being realistic, even with themselves, about the place they want to build these walls,” said Scott Nicol, a McAllen-based art professor, Sierra Club activist and member of the No Border Wall coalition. “And next time, instead of just soil and plants, you’ll have this 30-foot concrete-and-steel monstrosity washing down the river during a flood and threatening people downriver.”

Beyond fences hurtling downstream, the wall poses hydrological threats to fronterizos on both sides of the Rio Grande. In 2010, for example, the river swamped both a low-lying Roma neighborhood known as the De La Cruz colonia and several blocks of Miguel Alemán. Had the fence been in place, more water would have been shunted south, a threat to Mexican lives and a potential violation of a U.S.-Mexico treaty governing the Rio Grande. In a September 2008 document first reported by Texas Monthly, CBP contractors admitted as much: “The risks associated with the potential flooding on the Mexican side of the fence could range from minor property damage to the loss of life. … Mitigating the impacts of flooding from the U.S. side of the border is unattainable.”

Local border officials and activists, not to mention the federal government’s own engineers, have for years decried CBP’s goal of building a massive border fence in the Rio Grande floodplain. Yet Trump is plowing ahead, planning construction in Starr County as soon as this fall, at a cost of $25 million per mile. New documents obtained by the Observer show that the administration is relying on flood assessments that experts say are based on unreliable assumptions at best, and, at worst, reverse-engineered to downplay flooding risks. Meanwhile, South Texas officials — those best-positioned to explain the folly of Trump’s endeavor — have been kept in the dark, routinely denied even basic information about the plans for their towns. If anyone in Washington, D.C., would listen to them, they could explain that Trump’s border wall is being built on shifting sand.

–

After George W. Bush left office in 2009, Barack Obama graciously agreed to finish building 55 miles of border wall in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, specifically in Hidalgo and Cameron counties. Though landowners fought back and the project was plagued by incompetence and corruption, that mileage — which runs intermittently from the tiny town of Peñitas to Brownsville, near the Gulf — was the easy stuff. All of it was built on or behind existing river levees, an approach that mostly eliminated flooding concerns. But there are no levees in Starr County and far-western Hidalgo, and the urban areas that punctuate the otherwise rural swath of thornscrub are developed right up to the Rio Grande. That leaves the federal government with a dilemma: Either build the wall right along the river, risking worsened flooding and treaty violations, or move the wall further inland, putting dozens of homes in the barrier’s path and raising the politically disastrous prospect of mass evictions.

— In a Warming World, the Fight for Water can Push Nations Apart — or Bring Them Together

— New Border Walls Designed to Flood Texas Towns

— Documents Reveal Where Trump Plans to Build His Wall in Starr County

A decade ago, by seizing riverbank land like RGC-1066, the Bush administration showed a preference for long-term flooding risks over immediate displacement of people. But border officials’ plans hit a wall: a little-known agency called the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC). A binational body headquartered in El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, IBWC is tasked with enforcing treaties that forbid the United States and Mexico from building structures that would flood the other nation, or shift the border by altering the Rio Grande. IBWC polices the border by policing the river. From 2008 to 2011, both the Mexican and American sections of the agency stood firm against the much larger and more politically powerful Department of Homeland Security, preventing the erection of 14 miles of border fence in Roma, Rio Grande City and the tiny town of Los Ebanos.

Over the course of three years, IBWC rejected a series of CBP flood studies on those 14 miles, insisting the data showed unacceptable flooding impacts along the river. By 2010, funding to build the border wall had evaporated, and it looked like the Starr County wall was dead in the water. But CBP kept lobbying IBWC to change its mind, and in 2011 that persistence paid off. The U.S. IBWC broke with its Mexican counterpart, signing off on a new study that used controversial software and a different set of assumptions. In the past, Michael Baker International, the engineering firm hired to do the studies, had analyzed a worst-case scenario in which the fence would become completely clogged with debris during a flood, creating an impermeable barrier that would push the swelling river farther into Mexico. Now, the firm dropped that worst-case scenario and instead posited a mere 10 to 25 percent blockage, yielding much more favorable results.

Al Blair, an Austin civil engineer who reviewed the 2011 study, says that analysis is unreliable, in large part due to the software used: “The 2011 model was a proprietary, unstable, very questionable model,” he told the Observer. In February 2012, the Mexican IBWC obtained a copy of the software and ran its own test, getting a wildly different result: Flooding would increase on the Mexican side by 40 to 100 percent, blowing past the treaty threshold of 5 percent. Nonetheless, the U.S. IBWC unilaterally approved the fence project in 2012.

Stephen Mumme, a political science professor at Colorado State University who studies the IBWC, said the U.S. section succumbed to political pressure and made an illegal decision. “It has to be a binational thing, and technically the United States is in violation of that treaty,” he told the Observer — meaning Mexico could sue in an American court or at the International Court of Justice in the Hague.

Though Mexico never withdrew its opposition, the issue went quiet as funding to build the fence vanished. Until, of course, a Manhattan billionaire won the U.S. presidency. In March 2018, Congress authorized $1.375 billion for new and replacement border wall, including $196 million for Starr County. CBP went to work quickly, re-upping its plans to build in Roma and Rio Grande City and swapping out Los Ebanos for the slightly larger town of La Grulla, some six miles west. Quietly, the agency also paid Michael Baker International to do a new flood study, finalized in May 2018, of a 63-mile stretch including all of Starr County and Los Ebanos. This time the firm used standard government-developed open-source software. But yet again, the engineers changed the inputs, now positing 35 percent obstruction across the entire stretch, offering no justification for the new assumption.

“Next time, instead of just soil and plants, you’ll have this 30-foot concrete-and-steel monstrosity washing down the river during a flood and threatening people downriver.”

Larry Dunbar, a Houston environmental engineer who formerly worked for the Army Corps of Engineers, said the assumption is conjecture. “Thirty-five percent is just a guess — there’s no standard,” he told the Observer. “If they just say, ‘Well, we assume this [level of] blockage and that’s all,’ that tells me there’s no scientific basis for it.”

It’s possible, Dunbar said, that the engineers just chose the highest level of obstruction that would yield the desired results. Even so, the report reveals flooding threats. In small patches just upstream and downriver of Roma’s De La Cruz colonia, for example, the study shows the fence will increase flood levels by three to six inches, a violation of IBWC’s rules. The study also shows the fence diverting some water from Roma into the heart of Miguel Alemán — well within the rules, but still troubling, especially if the engineers lowballed blockage. Dunbar cautioned that even slight increases in flooding matter. “If you have a flood that comes one inch below the slab of your house, and the fence causes a three-inch rise, now you have the exact same flood and you have two inches of water in your home,” he said. “That’s an impact.”

Then there’s the study’s limited scope. Like the analyses that came before, the report quantifies only the fence’s impact on flooding from the Rio Grande — the question legally relevant to the IBWC. The study ignores how the fence might block water draining toward the river through arroyos and paved streets, causing the deluge to back up into Texas border towns. That blind spot means the reports don’t really assess the danger to Texas communities, according to Billy Moore, a longtime Washington, D.C., lobbyist for the Texas Border Coalition and an avid opponent of the wall. “If you’re trying to assess risk, you would look on both sides of the wall, at the threat to people and communities and livestock and wildlife and ranches on the northern side … [but] the purpose of this study is to persuade the IBWC,” Moore said.

Lori Kuczmanski, a spokesperson for the American section of IBWC, referred all border wall-related questions to CBP, stating only that “they’re aware of our requirements.” CBP spokesperson Rick Pauza did not respond to most specific questions, but said that “after extensive modeling,” the U.S. IBWC had signed off on CBP’s plans for the 8 to 12 miles funded in 2018 for Starr County. The agencies, he added, would continue collaborating on the rest of the wall. The Observer also reached out to the Mexican section of the IBWC for comment on the May 2018 flood study. José de Jesús Luévano, a spokesperson, seemed to suggest that his agency had not been consulted. “We are in the process of receiving the information from the U.S. Section of the Commission and reviewing it,” Luévano said in a March email.

–

When Freddy Guerra, Roma’s 33-year-old assistant city manager, thinks about the border wall, he recalls the flash flooding that struck his town in August 2008. A Roma native and University of Texas at Austin graduate, Guerra previously served as mayor. For Guerra, who boasts an encyclopedic knowledge of Roma, the 2008 deluge was a stark example of the threats the feds’ flood reports fail to address.

— Documents: CBP Ignored Federal Biologists’ Input on Border Wall

— Texas Teacher Could Lose Her Home If Trump Gets Any More Border Wall Funding

— All Walled Up

On August 18, 2008, the thunderstorms gathered before dawn, first soaking the sprawling ranchlands north of Starr County’s border towns before coalescing over Roma and the neighboring hamlets of Escobares and Garceño, lashing the area with a foot of rain in only six hours. In Roma, Arroyo Roma slices through the town from northwest to southeast; normally dry, the stream suddenly raged that morning, filling houses in the floodplain with up to five feet of water. “Those houses shouldn’t be there, but there was no regulation back then, there was zero planning,” said Guerra, referring to the 1970s and ’80s, when many of the homes were built.

In all, some 1,000 homes were flooded in the area, prompting more than 200 evacuations and causing millions of dollars in damage. More rain followed, and in the course of a week the area got nearly a year’s worth of precipitation — the kind of freak weather event that will grow more common as climate change accelerates.

Here’s what Guerra and other locals fear. Arroyo Roma pours into the Rio Grande near Roma’s De La Cruz colonia; there, documents show, the feds plan to build the border fence right up to the creek’s mouth. As the arroyo jumps its banks during a flood like 2008, the water will crash into the fence and begin clogging it with debris, water will skitter farther upstream and downriver on the north side in search of egress, and as the arroyo’s discharge into the Rio Grande slows, the creek will back up throughout the city, worsening flooding. And that’s not the half of it: Guerra says there are seven other arroyos in Roma that need to drain freely into the river during floods, all of which could be affected by the fence.

Similar scenarios have played out in Arizona. On at least three occasions between 2008 and 2014, border fencing in southern Arizona was clogged with debris after monsoon rains swelled southbound washes, leading to major flood damage in the areas of Lukeville and Nogales. On two of those occasions, 40- and 60-foot sections of fence collapsed.

For the last year, Guerra has been dogged not only by visions of worsened flooding, but also by a lack of basic transparency. For months, he and other city officials begged CBP to tell them exactly where the wall would go in their community. Would residents near the river be displaced? Would the city’s long-term plan to expand its port of entry be thwarted? It was too early in the process to know, CBP insisted. The information was not available.

“It has to be a binational thing, and technically the United States is in violation of that treaty.”

Then, in January, a federal contractor posted a ream of documents on a website for subcontractors interested in bidding on a wall contract. Those documents, which were leaked to the Observer and the McAllen Monitor, included the flood analysis that Baker had quietly finalized eight months earlier and a set of preliminary engineering designs that showed in great detail where the wall would be located in Roma, Rio Grande City and La Grulla.

Guerra first learned of the detailed plans for his town from press accounts. “You mind if I ask where you got that information?” Guerra asked me in early February when I called him for comment. “Because we’ve been trying to get a copy and it’s been like pulling teeth.” The mayor of La Grulla and the city manager of Rio Grande City, I learned when I called them, hadn’t seen the documents either.

Noel Benavides, a 76-year-old former Roma city councilman whose family roots in the town date back to the 1760s, said the lack of transparency stretches back a decade. “No communication, that’s always been the problem,” he told the Observer. Benavides, who owns parcels of land beneath Roma’s bluff and downriver of the De La Cruz colonia, has been battling the feds in court since 2008. He’s one of few Roma landowners who have refused to let the government even survey their property. “They come in aggressively with the attitude that this guy is not cooperating, we need to get after him and squeeze him as best we can, bleed him to death,” Benavides said. “I’ve been bleeding for 11, 12 years now — and my blood count is still high.”

When I visited Roma City Hall in March, Guerra showed me maps where he’d layered the leaked engineering designs onto satellite images of his town to pinpoint exactly where the wall would go. He had also drawn his own alternative proposals onto the map. What if the wall was moved closer to the river just downstream of the international bridge connecting Roma and Miguel Alemán? That would leave room for a new staging area for imports and exports. The city, he explained, has hoped for years to expand its port of entry, one of the town’s few economic drivers. He had also compiled renderings of a low concrete retaining wall, an alternative structure that would be less disruptive for the town.

Guerra had planned to present that information at a meeting between CBP and Starr County officials held the day before I arrived in Roma, part of a new consultation process mandated by Congress in February. But he said a CBP official told him to “forget he ever saw” the designs — the agency was going to draw up a new path for the wall after talking with local officials, then commission a new flooding study. (A CBP spokesperson confirmed those plans).

“I’ve been bleeding for 11, 12 years now — and my blood count is still high.”

In a way, Guerra finds himself back where he started: wondering where the wall will go. He’s hopeful that CBP will now accommodate the city’s port of entry plans, but beyond that he’s not holding his breath. CBP officials, Guerra said, made their priorities clear during the meeting: Border Patrol concerns were paramount, followed by treaty obligations, then local concerns. Plus, Congress stipulated that its funding was only for steel fence designs, likely nixing the retaining wall idea. Guerra estimates that whatever gets built will be “95 percent” the same as the leaked proposal.

Pauza, the CBP spokesperson, didn’t respond directly to questions about special accommodations for Roma. “Many considerations are made to determine the strategic alignment for the border barrier to include illegal cross border activity, hydrology and topography studies,” he said. “When and where possible, CBP works with local stakeholders to mitigate the impacts.”

During my March visit, Guerra guided me out of City Hall onto Roma’s historic plaza, which sits atop the imposing river bluff. A ring of 19th-century buildings made of river sandstone, caliche limestone and molded brick, the plaza feels like something yanked from an old Western. Guerra and I threaded our way down from the plaza to the area nestled beneath the bluff, where the 2010 flood claimed much of RGC-1066. As we stepped onto the caliche access road, a Border Patrol agent working his way through a dense thicket of vegetation called out to us to “be careful, there’s a lot of smuggling here.” Guerra nodded politely.

At the end of the road, Guerra nodded toward a water pump station, a crucial piece of the city’s infrastructure sitting in the path of the proposed border wall. How would the feds build around it, Guerra wondered. Would they pay for its relocation?

Like most local border officials, Guerra was raising concerns that never enter the national discourse about the wall, municipal worries that don’t drive internet traffic or nag the president as he golfs at Mar-a-Lago, but that keep the leaders of these overwhelmingly Hispanic towns up at night. (At times, Guerra said, Republicans in Washington, D.C., seem to dismiss the border as a region of “just Mexicans — on either side.”) Long after the rest of the nation forgets about Trump’s wall, however many miles he ends up building, locals like Guerra will still be managing the consequences.

Guerra gestured toward Miguel Alemán. On the Mexican side, he lamented, people still fish and recreate and celebrate holidays; on the U.S. side, it’s only Border Patrol and the occasional maintenance worker checking on the pump station. Rather than a towering wall, he envisions a sort of waterfront promenade, something to restore civic life along the river in his hometown. For a moment, we both just take the river in, its flow low and calm, for now.