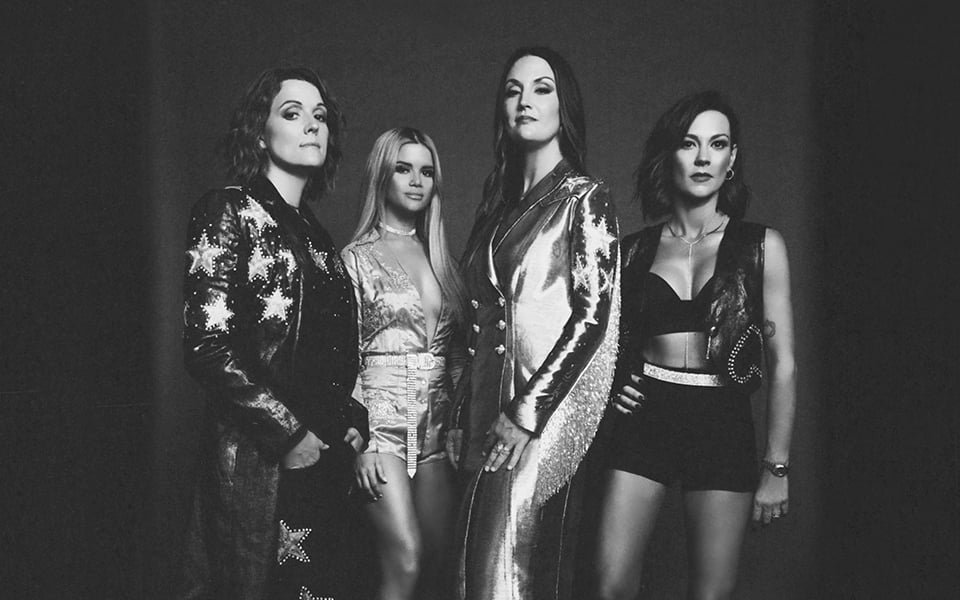

The Highwomen Are the Superbly Talented, Feminist Supergroup Country Music Needs

On a stunning self-titled album released this week, the four musicians—two of whom are Texans—explore domesticity, motherhood, love, and loss.

In 1973, fresh from recording her raw, woman-to-woman plea to spare her relationship, Dolly Parton mixed “Jolene” in Nashville’s RCA Studio A. She wouldn’t return to the space, the birthplace of some of country’s finest cuts, until almost five decades later—when the Highwomen came calling.

The newest country supergroup introduced themselves to the world in July, anchoring an all-female headlining set at the Newport Folk Festival. Aptly titled ♀♀♀♀, it included guest appearances by Sheryl Crow, Maggie Rogers, and Parton. In the lead-up to Newport, country’s leading lady rehearsed with the Highwomen in Studio A, where they had just finished recording their debut album.

“It was like full-circle,” said vocalist and fiddler Amanda Shires. “So much great energy. I wanted to celebrate the whole time, I think all of us did. But we were postponing our celebrations because none of us are very good at being hungover.”

Shires, a Lubbock native, began envisioning the Highwomen with three-time Grammy Award winner Brandi Carlile in 2016. The collective, rounded out by Nashville hit writer Natalie Hemby and Arlington’s country queen, Maren Morris, was designed as an answer to the male-dominated country charts.

“I have a daughter, and she shows musical tendencies,” Shires said. “The only thing that’s scary for me about the music industry is operating in a genre that’s not as well represented as it should be.”

A study released this April by University of Ottawa professor Jada Watson confirmed with data what Shires has known for years: There is a scarcity of women on country radio. Analyzing weekly charts compiled by Mediabase, Watson found that in 2000, spins by male artists outstripped women 2.1 to 1. By 2018, that gap had widened to 9.7 to 1.

That dearth of women, Shires says, has promoted the idea that there’s a limited number of “spots” that women must vie for. Her answer to that? She’d pack one with some of the biggest names in the business.

“I wanted to make it where the women in the genre, and within all scopes of music, could be on better terms—be friends and make it less like a competition, more like a squad,” she said.

In 2000, spins by male artists outstripped women 2.1 to 1. By 2018, that gap had widened to 9.7 to 1.

On their stunning self-titled debut, out September 6, the Highwomen embrace that mentality, sharing lead vocals and writing credits on songs that plumb quotidian realities for many women: domesticity, motherhood, love, and loss. They are upfront with their frustrations, singing about the added pressures of womanhood and femininity (“Redesigning Women”), the relentlessness of parenting (“My Name Can’t be Mama”), and the male gaze in lesbian relationships (“If She Ever Leaves Me”).

In a way, the Highwomen are picking up the mantle for Parton, someone who Shires notes has been singing about domestic life “since the beginning.” But the group also purposefully subverts tropes within the genre. The title track, which kicks off the album, rewrites the mythos of the Highwaymen—the 1980s collective of Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Willie Nelson—with a feminist bent. Instead of the continual reincarnation of a starman, the track (cowritten by Shires, Carlile, and the song’s original writer, Jimmy Webb) preserves the stories of women who have flouted tradition throughout history: a Salem “healer,” a traveling preacher, a freedom rider.

The Highwomen are part of a recent wave of all-female collaborations in country music. Days before her album release with the Highwomen, Maren Morris dropped a new song with Lindale native Miranda Lambert, whose project the Pistol Annies released an album in late 2018 after a five-year break. In June, the Dixie Chicks announced that after 13 years, their long-awaited return was imminent.

The swell, Shires believes, is a direct reaction to a hostile political climate.

“I think a lot of it has to do with social conscience, collective conscience,” Shires said. “I think there’s a lot of darkness in the world, and like the Beatles we’ve got to get by with a little help from our friends. It’s not a time right now that anybody feels like being isolated or alone.”

The project seems to be a musical manifestation of a situation described in the song “Crowded Table”: “I want a house with a crowded table / And a place by the fire for everyone / Let us take on the world while we’re young and able / And bring us back together when the day is done.”

At least on the surface, the Highwomen is a polished melding of minds and talents, not an obvious middle finger to the Music Row elite. There aren’t direct calls to burn down bro-country culture. Much like Parton—who Shires calls “the original Highwoman”—the band’s resistance lies in their very existence as women who refuse to accept the status quo.

“Elvis wanted to get ‘I Will Always Love You’ from her and she said no,” Shires said, referring to Parton’s choice not to hand over the publishing rights to her biggest hit to the King of Rock and Roll. “How many balls does that take to say ‘no’ to Elvis?”

None, apparently.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Professor Trill: Rapper Bun B on Port Arthur, resilience, and the meaning of trill.

-

Thousands of Rape Kits in Texas Went Untested For Years. Lavinia Masters Is Ending That: The Lavinia Masters Act is the culmination of more than ten years of Masters’ advocacy in Texas, where a backlog of about 20,000 untested rape kits was identified in 2011.

-

The Death of Mobile Polling Places Could Shrink Early Voting in Texas: Thanks to a new state law, rural and elderly voters are among those who could lose their early polling places next election.