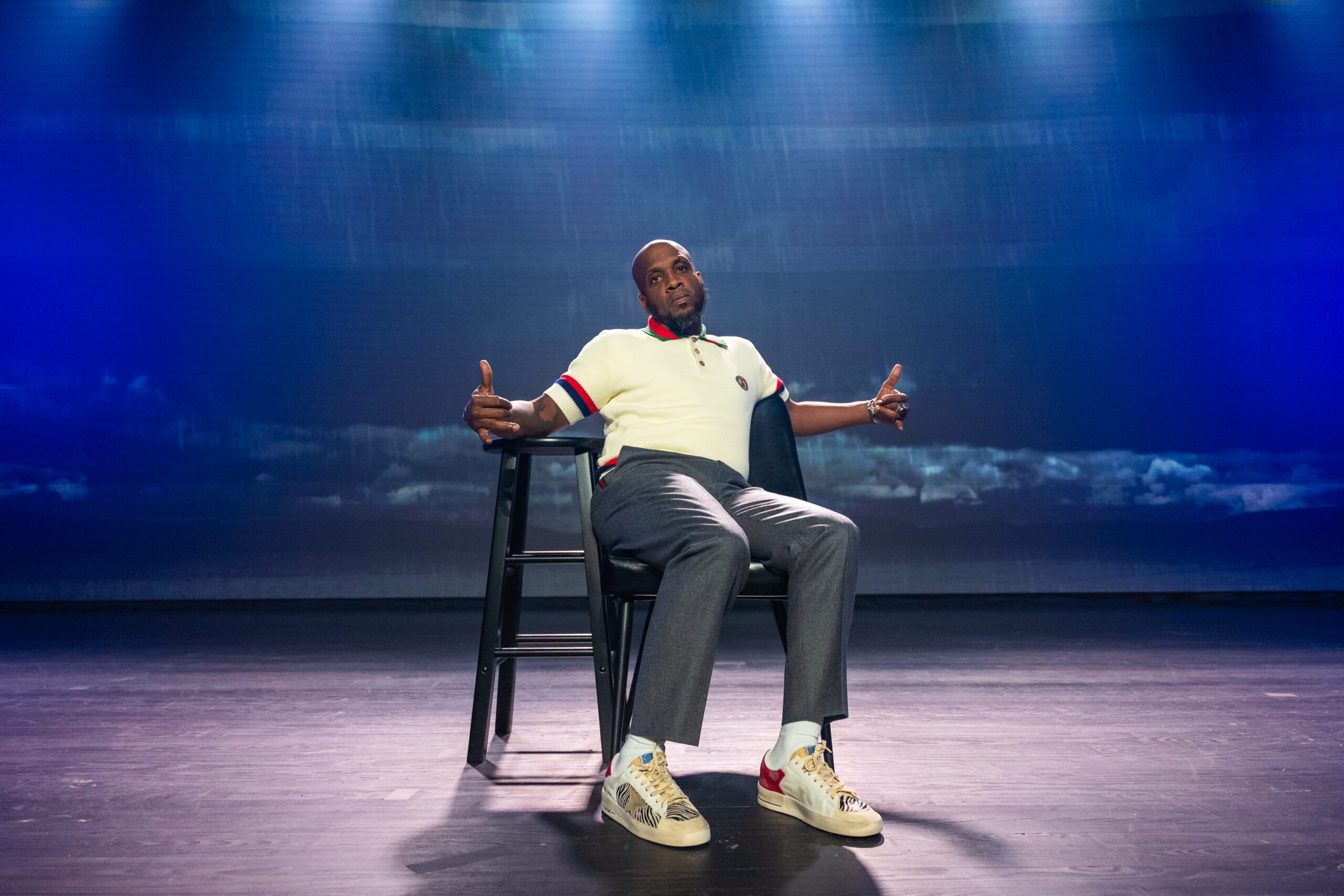

Shaping the Narrative: Nate Blakeslee Discusses a Pivotal Moment in Observer History

Blakeslee sought to elevate the Texas Observer’s writing while righting wrongs in Tulia and throughout the state.

A version of this story ran in the May / June 2024 issue.

Award-winning journalist and author Nate Blakeslee grew up in Arlington and devoured every book he could find. He majored in political science and joined the University of Texas at Austin’s American Studies graduate program, but then took a detour. In 2000, Blakeslee wrote a story for the Observer about a drug bust in Tulia that reverberated nationwide. His coverage led to more than a dozen criminal exonerations and changed lives and drug task forces. After three years co-editing the Observer, Blakeslee resigned to write a book about Tulia.

TO: You dropped out of grad school to try to write for the Observer. That has to be a first…

I had this idea that grad school was where all the radicals were. I never really quite found them, but I did find the Texas Observer and I found this community of leftists in Austin, which was very vibrant in the ’80s and ’90s.

How did you convince them to hire you?

In those days, the staff was very small, it was like four or five people, and there wasn’t much money. They hired me to do a couple of freelance stories. I was very used to being broke as a graduate student, but now I was even broker. So I tried to convince them that there must be some way to bring me on at least part-time. And they did, as a circulation manager. I had administrative duties and I would also report, on a part-time basis.

The first big story I did was about this nuclear waste dump that they wanted to build in Sierra Blanca, east of El Paso. My girlfriend at the time was leading the opposition to it, which at most magazines would be a disqualification for you to get that assignment. But at the Observer, at that time, they were like, “Who knows more about it than you?”

They were part of a long tradition of crusading journalism. It wasn’t new and they wore it on their sleeve, even back to Ronnie Dugger days. Ronnie would say, “You see an injustice, it’s one thing to be objective. It doesn’t necessarily mean you need to be impartial.” That was his perspective, and that very much carried forward and still was the perspective when I came to the magazine.

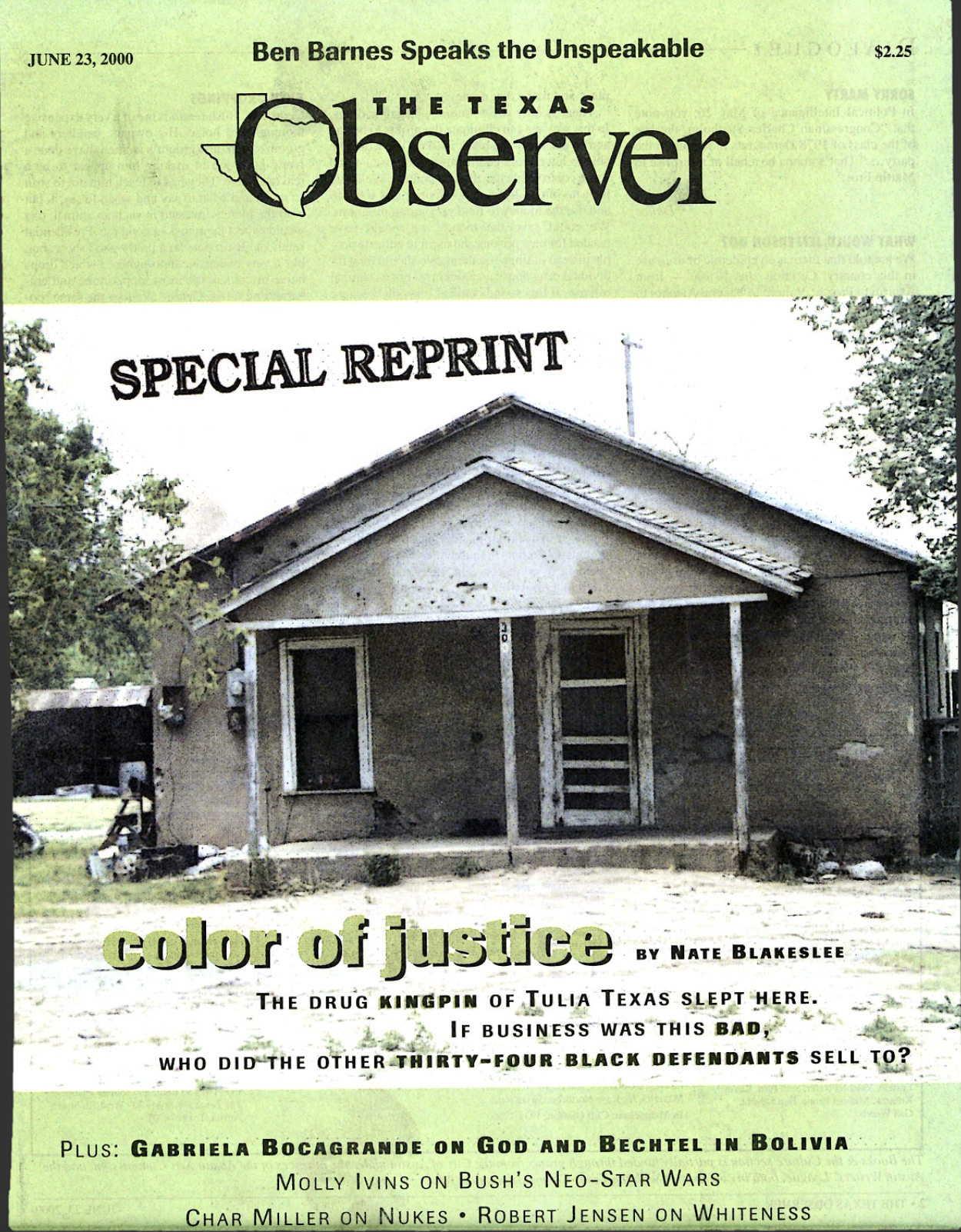

As you reported, a man once recognized as Texas’ “Outstanding Lawman of the Year” turned out to be quite the fraud. How did the Tulia story unfold?

Several dozen African Americans had been arrested for allegedly selling cocaine to an undercover police officer. Some locals decided that the bust was unfair and had sort of despaired of getting the Amarillo or Lubbock papers to cover it and started writing to other publications. I had done a couple of drug war stories and so I got the letter, I read it.

The thing that jumped out at me was that all of the defendants were African American in a town that had a very small African American community. And then the sentences given out were really long for very small amounts of cocaine. Like a couple of hundred dollars’ worth of cocaine sold was resulting in sentences as if they had murdered someone, you know, 50-60 years.

So that’s why I went. But when I got out there, it became evident that it was a very different story. There was no evidence against them other than the word of this one undercover narcotics officer who never wore a wire, never had a second officer to corroborate, no drugs recovered during the roundup of these suspects. And so then the question became, “Were these cases even legitimate to begin with?”

I didn’t realize what a head-slapping story it was until I got out there. And then, I called [my editors] and said, “I don’t think these people actually committed these crimes.” It’s not about their race, and it’s not about their sentences. It’s about the narc and the utter lack of supervision of the narc.

He was a piece of work. But his dad was a famous Texas Ranger, and he had been living off of that for years and years, getting jobs based on it, trying to live up to his dad’s reputation and utterly failing until apparently he had become the greatest narcotics officer in the state of Texas. But it was all a lie.

What was the reaction to that first story?

An amazing amount of bounce. The New York Times and the LA Times both rereported the story for Page 1 on the same day, neither mentioning that they had read it in the Texas Observer. Fortunately, our board chair was Molly Ivins, who knew the editor of the New York Times. She called and said, “What the hell?” And that same reporter was, I assume, made to come down and profile myself and Karen Olsson, who was my co-editor—the young editors of the Texas Observer making a splash with their reporting.

And then once the Times did it, everybody followed, it just became this huge national story.

How did you leave your imprint as co-editor?

Karen and I found a new layout person, Julia Austin, who was very creative. There had not been a lot of emphasis on how the magazine looked, it was more about just conveying information. And that was also true for the website, it was really rudimentary. So we redesigned the website too. We wanted to be New Yorker writers. That’s what we’ve read, and we wanted to write that kind of stuff.

Tell me about y’all’s notorious happy hours.

When you work at a magazine, you get a lot of advance copies of books if you do book reviews, which we very occasionally did. You’re probably used to selling your books for $0.50 a piece at Half Price [Books]. But if you have a brand-new hardcover book, you could actually get some money. We would take big boxes of books over there and sell them and buy a keg with them and have these happy hours like once a week.

We read them, we reviewed some of them, we sold them and we drank them with other people that we knew. A lot of really interesting people were coming around. I won’t say it was glamorous, but it was good company, stimulating company.

What is the Observer’s legacy?

For a long time, it was a voice in the wilderness for progressives in Texas when there weren’t that many different places you could turn to for progressive thought and opinion.

The Observer has been willing, in terms of reporting, to tackle subjects that other papers weren’t willing to or simply had overlooked.

I think it’s a place with really solid reporting, a place that focuses on issues that other newspapers and magazines might miss. And now, alt-weeklies that we used to compete with have died off, and staffs are much smaller now, sadly, at the dailies.

It has become a time when you need a source for good reporting again, maybe as much as we ever have. It still has a wonderful fresh voice, the reporting is really incisive and just as useful and necessary as it ever was.

This interview, which is part of the Observer’s 70th anniversary coverage, has been edited for length and clarity. Support for our 70th anniversary interview series has been provided by KOOP Radio in Austin, which permitted its studios to be used for recordings.