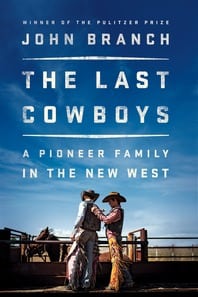

‘The Last Cowboys’ is a Wild Ride All the Way Home

Pulitzer Prize winner John Branch takes a fascinating dive into what it's like to make a living by horseback, both on the range and at the rodeo.

Confession: I’ve never ridden a horse. I’ve never baled hay or branded a steer or helped a cow give birth. Perhaps you think this should disqualify me from writing about rural Texas for the Observer, and perhaps you’re right. But ever since I was a kid, I’ve occasionally wondered what it would be like to live that life — to be a cowboy out on the lonesome range, breaking wild horses and drinking too much whiskey and feeling the breath of adventure on my face.

I suspect at least some of you have wondered the same thing.

For now, I am merely a writer, thriving on air conditioning and wifi, no more a cowboy than those pop singers who play ad nauseum on Country Music Television. That’s why I’m so appreciative of John Branch, a Pulitzer Prize-winning sports reporter for the New York Times, for giving me a little piece of the country life in The Last Cowboys, a fascinating dive into what it’s like to make a living by horseback, both on the range and at the rodeo. The book manages to deftly translate the niche, complex worlds of ranching and rodeo to a general audience. Branch uses clear prose and impeccable pacing to deliver a fly-on-the-wall perspective of life in the new American West, where urban sprawl pushes ever outward, the rain clouds seem to carry personal grudges and trying to earn a dollar might lose you two.

by John Branch

Norton

$26.95; 288 pages

The Last Cowboys centers on the Wright family of Utah. With names like Stetson, Rusty, Ryder and CoBurn, they’re some of the world’s best bucking bronco riders. Family patriarch Bill Wright runs a beef cattle ranch in the craggy canyons near Zion National Park, where he feels increasingly squeezed by federal regulators and a surging tourist industry. The rest of the Wrights — some of whom aren’t even old enough to drink — ride professionally in “saddle bronc” competitions at rodeos all over the country, hoping to scrape up enough winnings each year to compete in the National Rodeo Finals in Las Vegas.

Cody Wright, Bill’s son and one of the book’s main characters, has already claimed two world titles in saddle bronc when the tale begins. There’s a rodeo arena named after Cody in his hometown of Milford. On the family ranch in nearby Smith Mesa, Cody is Bill’s right-hand man, just as capable on the range as he is in the arena. His motivation is to compete in the National Finals Rodeo with his sons, who have also emerged as wunderkinds in the saddle bronc sport.

Branch followed the family for three years to cattle brandings, rodeos, hotel rooms, stockyards and everywhere in between. He seems to capture every lonely midnight cattle drive, every wild “bronc” romp, every moment of self-reflection as the Wrights vie to maintain their position as the best in their sport while trying to keep the family ranching operation afloat. “It was becoming clear that one peculiar way for the family to hold on to a dying tradition in the West was by dominating another,” Branch writes.

No shortage of ink has been spilled on the subject of rodeo. Fans of the genre might recall reading Chasing the Rodeo or Fried Twinkies, Buckle Bunnies, and Bull Riders. But The Last Cowboys does what those books do not. It shows the connection between rodeo and cowboying, how both are rooted in the lifestyles and traditions of the American West. Branch lures readers in with colorful play-by-plays — bones breaking, riders flipping and horses stomping; crowds hollering and dust swirling. But every so often he switches gears, finding Bill on the ranch in Smith Mesa, searching for cows in the fog and fretting over what the future may hold. The approach keeps readers invested.

Branch uses clear prose and impeccable pacing to deliver a fly-on-the-wall perspective of life in the new American West, where urban sprawl pushes ever outward, the rain clouds seem to carry personal grudges and the wild spaces trend toward safe spaces.

He deploys delightful turns of phrase to describe the stark Utah scenery: “The desert wore the dark like a heavy blanket,” and “The headlights reeled the black highway in and, like a treadmill disappearing underfoot, gobbled up the painted dashes on the pavement.” But Branch never lets the color get too purple, usually relating the story in a straightforward, matter-of-fact style that would make a daily newspaper editor beam.

Branch’s decidedly objective style carries forward even in circumstances that might raise readers’ eyebrows. For instance, the sport of saddle bronc riding is exclusively open to men; the only rodeo event that includes women and also counts toward the national finals is barrel racing. The Mormon faith, in which all the Wright boys are versed, is openly opposed to homosexuality. At one point in the story, 3-year-old Kruz is allowed to ride a pony with no adult nearby. The child is bucked, his jaw broken, his lungs filled with fluid. Luckily, the boy survives, but many readers would rightfully view such a lack of supervision as negligent.

Branch doesn’t judge, or if he does, he keeps it to himself. And the book is better for it, I think. The author expertly captures the thoughts, feelings, and predicaments of his subjects but doesn’t criticize or romanticize. He doesn’t cast the cowboy life in sepia tones, a potential pitfall for any book that approaches this subject matter. Branch doesn’t shy from family patriarch Bill’s struggles with alcoholism that momentarily tear the family apart, or from Bill’s son Calvin’s stints in jail and drug rehabilitation programs.

Any criticism I have for The Last Cowboys is minor. Near the end, Branch’s pace slows and he gets a little gummed up in the minutiae of ranching and rodeo. Still, chapter after chapter, I felt compelled to keep reading. I think it’s because the book carries with it some sort of universal appeal. Ranching and rodeoing are essentially gambles, endeavors undertaken when the Wrights put their time, money, family and health on the line. Nothing is guaranteed, and failure is always a possibility. Even those of us with neither hat nor cattle can relate to that: giving everything we have to get by in a world where we’re never completely in control. But we keep pushing onward, because what else are we gonna do?