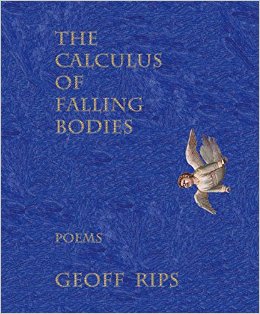

The Observer Review: The Calculus of Falling Bodies, by Geoff Rips

“The next time / you press your lips to walls,” Geoff Rips writes in “St. Matthew’s Passion,” “there will be certain walls / that are kissing back.” All of us should want to live in such a dwelling—I know I do, especially now, during National Poetry Month. Read The Calculus of Falling Bodies, Rips’ new poetry collection, and you’ll get the chance. Rips’ poems teem with gorgeous reciprocity.

The Calculus of Falling Bodies is wonderfully freighted—as it should be; this slim volume is a gathering of almost four decades of poems by someone who has dedicated himself to the written word. This commitment is made explicit in Rips’ introductory essay, a wildly interesting frontispiece that highlights friendships with some of the most important writers and subversives of the 1960s, a family relationship to poetry and work and the importance of people, place and justice for the author. Maybe best known for his journalism (especially for his editorial work at the Observer), Rips has written speeches, grant proposals and position papers, and novels: The Truth (New Issues Poetry and Prose) was published in 2008, and he is at work on another.

Rips’ devotion to language manifests on every page of the four sections of The Calculus of Falling Bodies. “Compost,” the first, starts with a poem of the same title. It begins:

By Geoff Rips

Wings Press

96 pages; $16

Grapefruit rind, onions’ outer skin, pliant celery stalks, lemon gone

soft and gray underneath, what’s left of what was used for soup

The poem continues to unfold, Whitmanic and expansive, through supple and dense lines that focus on a father/daughter relationship. As in many of these poems, here Rips weaves the mundane into the ecstatic: the rotting vegetable matter, the mysteriousness of heat, a young mind’s interaction with the majestic hugeness of her growing world. The poem closes:

Chemical reactions. No real reason for it, except that it’s work to do.

Orange rind, elm leaf, earthworm, the turn of my daughter’s hand,

generating heat, generating heat at the heart of it all.

There is much to love in the variety of The Calculus of Falling Bodies. The second section, “Resurrection,” consists of love poems and contains the most sensual lawn-mowing poem I have ever read. Rips’ journalistic prowess informs the observational mode of the pieces in “Personal Geography,” the book’s third section. Fundamentally, the fourth and final section, “The Calculus of Falling Bodies,” is about death and dying, but like so much of Rips’ work, these moments are celebratory—they are alive in their grief, in their meditations on the end.

Rips’ poetry is stylistically diverse. He plays with line and density and the relationship between observation and explanation, and he modulates tone masterfully. This is smart verse, informed by and often echoing lines from a range of important poets, from Allen Ginsberg and William Carlos Williams to Walt Whitman and Federico Garcia Lorca. And all of the variety in The Calculus of Falling Bodies is united by, in this reader’s eyes, three primary qualities: exactness, emotiveness and lines that remind us how to be alive by conversing with the larger world.

The Calculus of Falling Bodies is a magnificent collection—embodied wholly, viscerally, by the verve and emotional vitality of the collection’s last lines, from “The Art of Poetry”:

Nothing is too far away that it can’t almost be summoned back,

even the lost thoughts of the living,

even the dead thoughts of the dead. Out of reach

but not so far. Ain’t it a shame.

The ghosts almost come alive.