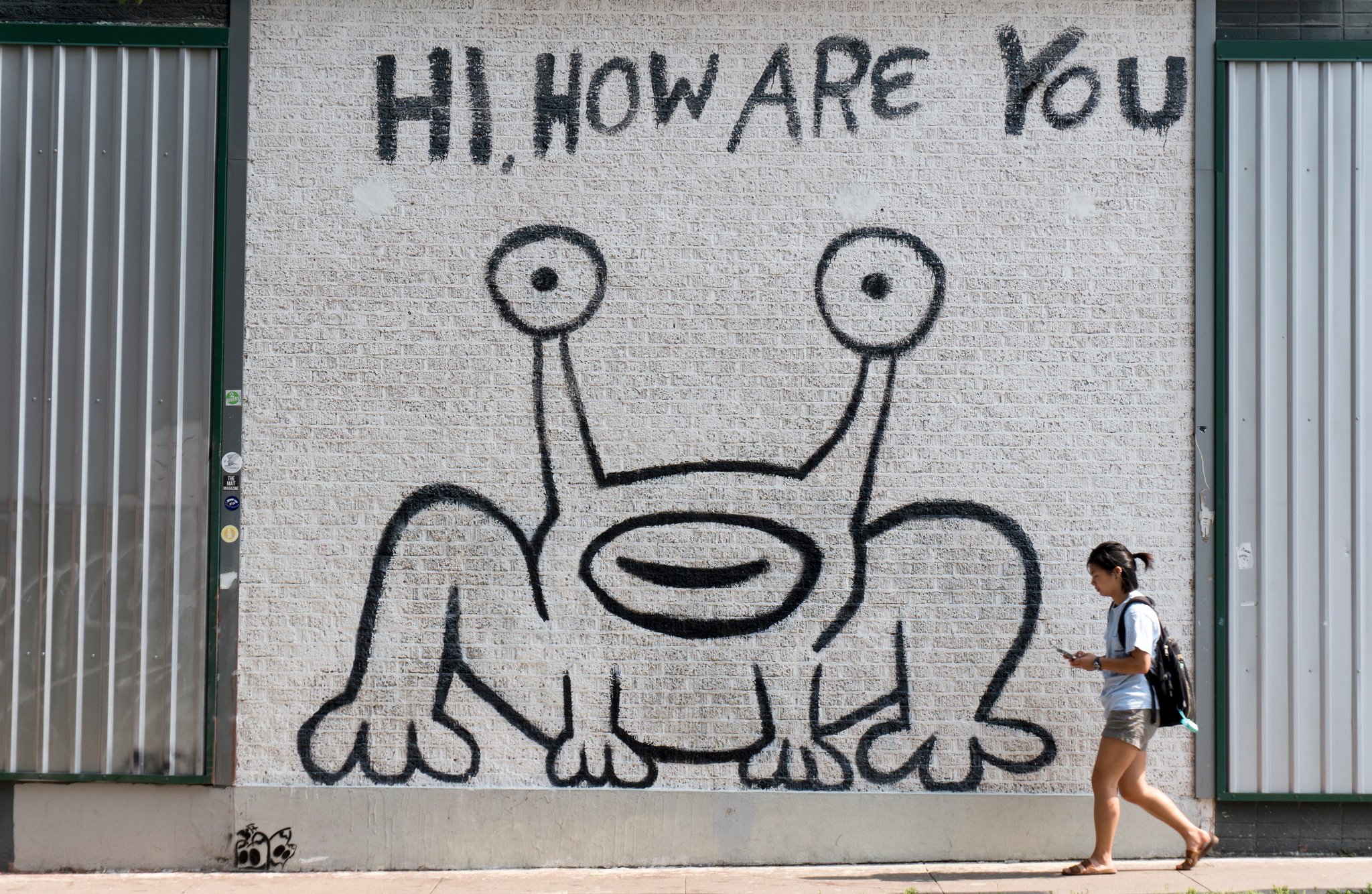

The People’s Frog

Austin’s “Hi, How Are You” frog mural on a building at 21st Street and Guadalupe is one of America’s most famous pieces of street art. It was painted by Texas outsider artist and musician Daniel Johnston, who, despite being mentally ill, has had songs covered by Tom Waits and Beck and his art displayed at the Whitney Museum. The iconic painting, a bug-eyed cartoon bullfrog named Jeremiah the Innocent, has been put on baby onesies, T-shirts and even iPhone apps. Johnston said, “It’s the way that the town remembers me.”

The frog mural represents a lot of things to people in Austin. To me, it’s a monument to a time when there was no point to cynicism, and street protest was the most viable form of activism I could imagine.

Street protest gets a bad rap these days, and for good reason. Despite hundreds of thousands of marchers during the lead-up to the war in Iraq, despite more than 1 million demonstrators nationwide rallying for immigration reform, despite even more people in London, Pittsburgh and Toronto protesting the G20 summits, the result was: a war with Iraq, a failed immigration bill, and agreements among G20 nations that took no account of the masses in the street.

The idea of a protest changing anything? Even teenagers have become too cynical to buy into that.

JohnsTon painted the mural in 1993 on what was then a record store, Sound Exchange. It quickly became a landmark. Something about the simple outline of a frog with a vague half-smile and those words—“Hi, How Are You”—connected with something whimsical. The painting is part of why I’ve made Austin home—I’ve always loved living in a city of people who could look at a simple mural and agree that it said something about who we were.

Ten years after the painting was commissioned, Sound Exchange closed. Eulogies for the “old Austin” abounded, as they do whenever a local business in the Keep-It-Weird district shuts down. I was as sad as anyone—I lived five blocks away, and Sound Exchange was my record store.

After several months, the building was rented to Baja Fresh Mexican Grill, a fast-food restaurant under the Wendy’s umbrella.

The morning of Jan. 5, 2004, a friend overheard construction workers at the site say that the day had come: They were scheduled to tear down the frog mural so it could be replaced with windows. I hustled over and found some workers taking pictures in front of the frog. They were sad, they said. Everybody in Austin liked the frog.

There have been numerous editorials about whether street protest still works. The Daily Kos’ Markos Moulitsas devoted a chapter of his 2008 book Taking on the System to the question, and other bloggers and pundits have been trying to find an answer. Mostly they conclude that it doesn’t. It’s hard to argue with the facts.

I was 23 in 2004, and those conclusions sounded cynical and closed-minded. So when I left the site of the soon-to-be Baja Fresh, I used the proto-social networking websites of the day (Friendster, etc.) to recruit people to think up words that rhymed with “frog” for chants.

A few months earlier, to protest the war, we’d marched in groups of several thousand down Congress Avenue, from the steps of the Capitol to the river, only to see our numbers underreported and our message lost among the Free Mumia/Legalize It/Free Tibet noise-to-signal ratio. For the frog—a local cause being protested by a local group of about 30—we obtained as much TV and print coverage as we’d hoped for.

The stories started to fall into a “Requiem for a Frog” line on how sad everyone was that the mural was being destroyed. One protester had an idea: Instead of railing about the frog, why didn’t we call the guy who was building the Baja Fresh?

John Oudt started the Texas Restaurant Group after selling the Barq’s root beer brand to Coca-Cola in 1995. Today his son Randall handles the day-to-day responsibilities of the company, but the elder Oudt oversaw the development of the Baja.

“It was quite a surprise,” he said when I asked what it was like when he got a phone call informing him that a few dozen protesters were outside his building. “I thought the painting was just an accumulation of graffiti,” he said.

When I spoke to him that afternoon years ago, I insisted that the mural wasn’t graffiti—it was art. Much to my surprise, Oudt heard me out.

“I’m not a young guy, and this isn’t my first rodeo” he said. “I’ve been involved in areas around universities before, and I knew that the attitudes that people have about you are extremely important if you’re trying to open a business in an area like The Drag.”

He met us at the frog site and apologized, said if he’d known it meant something to us, he’d have found a solution. As it was, plans had been approved, and everything was underway. He was polite and sincere, and offered to see if the workers could cut the mural out very carefully, if I had room for it in my West Campus studio apartment.

We shook hands, and he thanked us for letting him know about the mural. Walking home, I took the fact that he’d shown up as a victory, but the next morning, he called me.

“I couldn’t sleep last night,” he said before explaining that he’d decided to save the mural. We held a press conference that afternoon, at which he said he expect-ed it to cost him $50,000 in architect fees and lost revenue to preserve it, but that it was important to him.

The late House Speaker Tip O’Neill famously said that “All politics is local.” Most of the demonstrations held up as proof that protest doesn’t work have been about big national and international issues. A group in Toronto isn’t going to change what leaders in South Korea and Turkey and Australia decide about the G20; amassed immigrants in Chicago and Dallas aren’t liable to effect change on an issue that’s so divisive throughout the country; a bunch of people with signs down in Texas aren’t able turn heads in the Pentagon.

If I were still in my early 20s, that might sound like cynicism to me. When it feels hopeless, though, I just have to go back to my old neighborhood to see that big, googly-eyed frog to remember that when you keep your focus on your immediate world, you can be a lot more powerful than you’d have thought.

That afternoon in 2004, a few friends drove by while we were demonstrating. They’d been with me a few months earlier, marching through downtown to protest the war, and this time they thought what we were doing was funny—“You’re going to have to get a real job sometime, frog boy!” But when they drive down Guadalupe today, that mural is still there.

It means something different to them than it does to me, I’m sure. Just like it means something different to Daniel Johnston himself, or to the photography students at the University who shoot pictures of it every semester, or the guy on YouTube who put up a video of himself standing in front of it and explained that, “Standing before Daniel Johnston’s mural in Austin, Texas, was a highlight of my trip across the United States.”

To me, the mural means something about the kind of difference a person can make, and that O’Neill’s maxim was right. If I’d listened to the part of me that agreed that the wrongs of the world were too big to fix, all of us—my friends and I, Daniel Johnston, the photo students and the guy on YouTube—would be walking past the building where Jeremiah the Frog used to live and wishing we could bring him back.

Dan Solomon lives in Austin. His work has appeared in The Onion A.V. Club, Spin, Austin Monthly and Asylum.com.