The Poor in Texas Have Been Vastly Undercounted, New Report Finds

The federal poverty level fails to take into account 2.6 million struggling Texas households.

It ain’t cheap living in the oil boomtown of Midland, where the fracking frenzy sweeping through West Texas has led to an eyeball-popping spike in rent. In 2018, a two-bedroom apartment cost on average $1,460, a 28-percent increase from 2017. That’s about the same price as a similar apartment in Austin and about $200 more than the monthly earnings of a minimum-wage worker in Texas. As Midland rents rise, the working poor have been forced to scramble, taking on extra jobs and turning to nonprofits for help. “Just to even try to keep up with it, you have to have two or three jobs. It takes so much time from your kids,” a mother of four told the Midland Reporter-Telegram in May.

The federal poverty level — the standard used by the government to determine who should be considered “impoverished” — doesn’t reflect Midland’s income crunch. In fact, according to the standard, the percentage of Midland residents living below the poverty line dropped from 13 percent in 2010 to 8 percent in 2016; compared to Texas’ 2016 poverty rate of 15.6 percent, that’s pretty good. But don’t take that number at face value, said Stephanie Hoopes, the director of a United Way project that aims to more accurately assess poverty in Texas and 17 other states. The group released a report Monday showing that the federal government may be vastly undercounting poverty in Texas. As a result, poor Texans may face unwarranted obstacles to seeking government assistance.

“This is not merely an academic issue, but a practical one,” the report states. “The lack of accurate information about the number of people who are ‘poor’ distorts the identification of problems related to poverty, misguides policy solutions, and raises questions of equality, transparency, and fairness.”

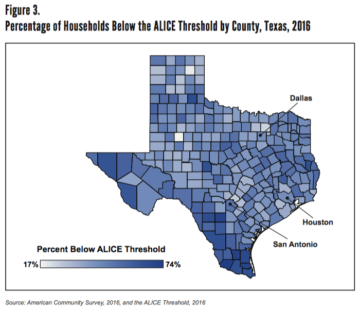

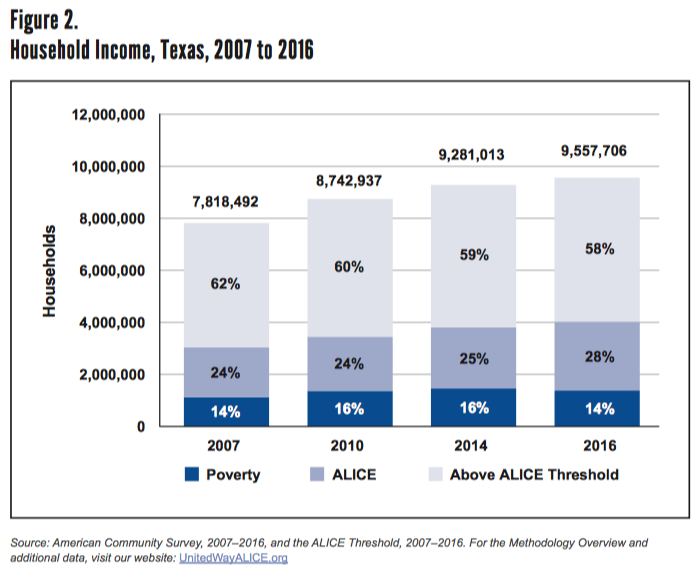

Hoopes estimates that the federal poverty level, which is used to determine eligibility for public assistance programs, doesn’t account for 2.6 million of Texas’ working poor, namely households with income above the poverty level but below a realistic cost of living. The residents tend to be from groups already at a higher risk for poverty, such as the disabled, elderly, undocumented immigrants and the formerly incarcerated. Rural and urban areas of Texas have higher percentages of folks living in this financial no-man’s land than the suburbs.

The United Way proposes a new system for measuring poverty, one that takes into account fluctuations in expenses from place to place and what it actually costs to live there. For example, by the group’s calculations, a family of four living in Midland County spends more on housing than anything else: $15,000 a year. Altogether, the family would need roughly $61,000 annually just to pay for the basics, which include food, child care and transportation. That’s more than double the federal poverty level for a family of four, which sits at $25,750. While federal estimates show that poverty levels in Midland County are relatively low, Hoopes found the opposite: The percentage of households unable to afford the basics is three times the federal number, and it’s slowly rising, from 32 percent in 2010 to 34 percent in 2016.

Statewide, the analysis found that 42 percent of Texas households make less than the cost of living. More than half of those make too much money to be eligible for many government benefits, but not enough to pay for basic expenses. If the federal poverty level were raised to be in line with a more realistic cost of living, impoverished Texas families would need an additional $79 billion in income or public assistance to hit the mark, the report says.

“[Benefits] are directly tied to a person’s income relative to the poverty line,” said Kristie Tingle, a research analyst at the Center for Public Policy Priorities, a left-leaning think tank in Austin. “Are the people who need this getting it? If too many families are food-insecure in Texas, we need to think about how to fill the gaps.”

Hoopes said some government agencies have tacitly acknowledged that the poverty level is unrealistically low. For example, in Texas, the eligibility cutoff for Children’s Medicaid is roughly 130 percent percent of the official poverty level. The federal Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which is administered by individual states, uses 150 percent of the poverty level in Texas. Still, poor Texans sometimes find that Medicaid, food stamps and other assistance programs are off-limits to them. Texas has some of the strictest eligibility requirements in the nation for its Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program; cash assistance to help people pay rent and utility bills only goes to four out of every 100 impoverished families in the state.

Back in Midland, struggling residents are increasingly leaning on the West Texas Food Bank for help, said Libby Campbell, the organization’s executive director. She said some of the folks who can’t afford food also don’t qualify for government assistance. “What happens if you’ve got people on fixed incomes who are elderly, or perhaps a single parent? … They still pay the price to live here because we’re in a boom,” Campbell said.