On January 19, 2018, shortly before 10 a.m., Robin Lafleur exited Texas Highway 290 at South First Street, as she did every morning on her way to work at Austin Habitat for Humanity. It was a cold, cloudy morning but Lafleur was in a good mood. She finally felt settled in her new home, which she’d bought less than a year before in Cedar Park, a suburb northwest of Austin. It was a Friday and she had happy hour plans with friends after work, so she was wearing one of her favorite outfits—maroon jeggings and a new mauve sweater with matching boots.

She doesn’t remember much about what happened next. As she merged onto the frontage road, a car stopped abruptly in front of her. She slammed into it. When she woke up, she was in a hospital gown at St. David’s South Austin Medical Center—nurses had cut her clothes off her body to take a CT scan. The concussion she suffered kept her out of work for more than three months. “I was told that to heal, I needed to sit in a quiet room and let the time go by,” she says. “It was horrific because the days went by so slowly.”

Before she moved, Lafleur had been renting an apartment less than 10 minutes from her office, but she wanted to own a home in the city where she grew up. She soon realized her nonprofit salary wouldn’t get her very far. If you can’t afford to buy in Austin, Lafleur says, “You’re left up a creek without a paddle. Or you use that paddle and you travel to Cedar Park.”

As the price of housing in Austin has skyrocketed, low- and middle-income people like Lafleur have left the city in droves, seeking cheaper housing in the suburbs strung along Interstate 35—Round Rock and Pflugerville to the north, Buda and Kyle to the south, all of which have at least doubled or tripled in population since 2000. After she closed on her house, Lafleur joined the thousands of other people who crowd I-35 every day to get home, sitting in traffic for nearly 90 minutes to travel 25 miles. “At this point, driving on 35, which I still do every day, it’s a very, very stressful and anxiety-causing event,” she says.

The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) wants to fix Lafleur’s commute. In early 2020, after nearly three decades of planning, discussion, and community input, the Texas Transportation Commission, which oversees TxDOT, voted to allocate $7.5 billion to the I-35 Capital Express Project, which includes plans to expand an 8-mile segment of I-35 through central Austin.

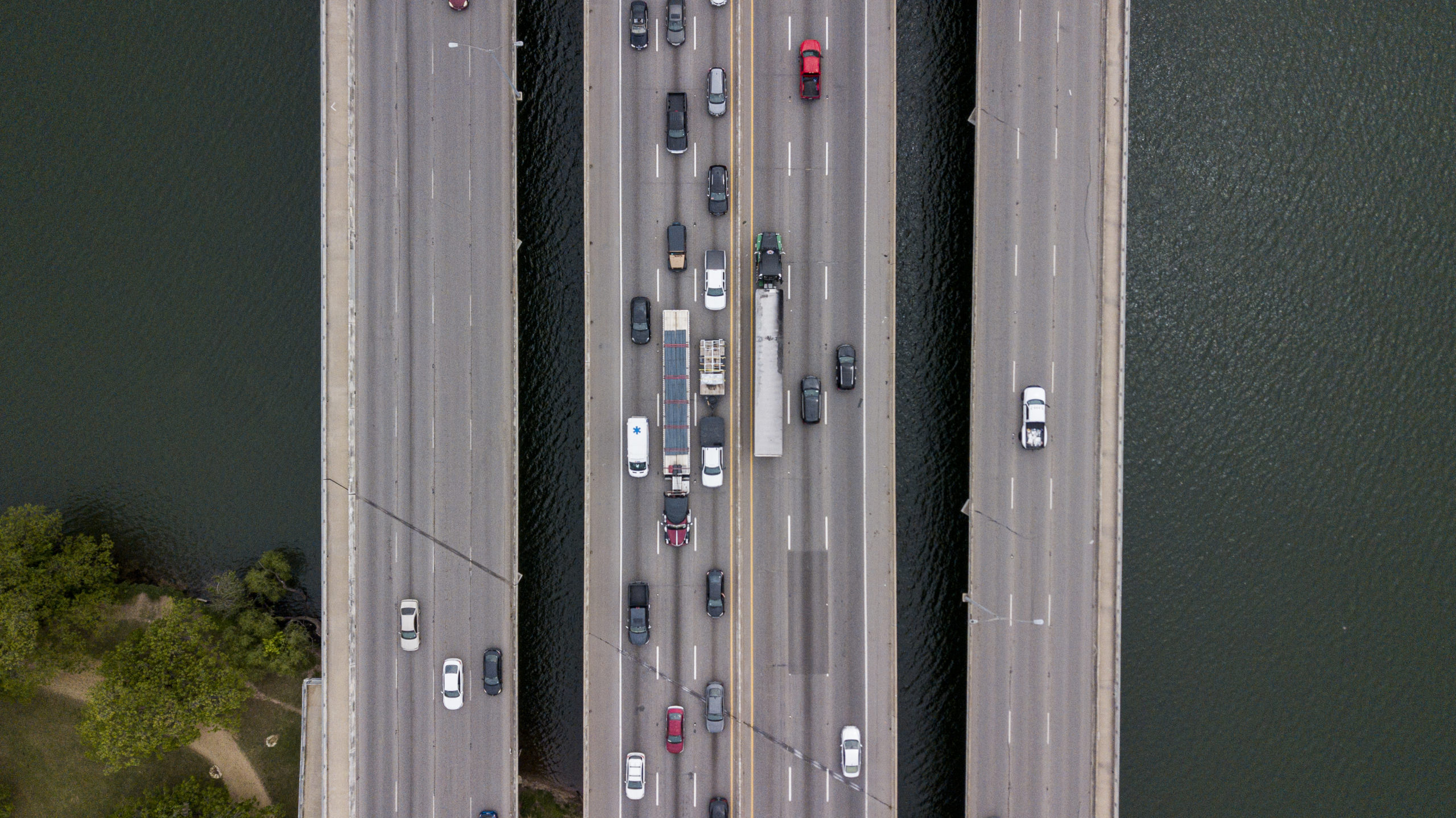

The stretch of I-35 that passes through downtown Austin is both the most congested stretch of highway in the state and the most dangerous roadway in the city—1 in 4 traffic fatalities in Austin occur on the highway or its frontage roads. The goal of the expansion, says Susan Fraser, the program manager for the I-35 project, is to make the highway safer and more efficient for the more than 200,000 vehicles that use it every day. TxDOT plans to do that by adding managed lanes, restricted to vehicles with two or more people in them.

“I know there’s the mindset that if you build it, they will come,” says Diann Hodges, a spokesperson for TxDOT’s Austin district. “Well, they have come. Anybody who lives or drives in Austin knows the congestion that we’re dealing with. So we’ve got to make improvements to the road that is there to make it accessible to everyone.”

Texas’ population is projected to nearly double by 2050. Most of that growth will happen in urban areas like Austin, which has been the fastest-growing major metropolitan region in the country over the past decade. Texas leaders have decided that to accommodate that growth, the state urgently needs “to get new roads built swiftly and effectively,” as Governor Greg Abbott has promised. Despite the fact that it is much more efficient, sustainable, and safe to move people through crowded cities by other modes—like buses and trains—TxDOT spends essentially all of its funding on enabling seamless car travel. Since 2015, TxDOT has committed more than $25 billion to “congestion relief” projects across the state and has plans to expand highways in Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, Fort Worth, and El Paso.

This is how transportation departments across the country have functioned for decades—building ever bigger highways to fix traffic—despite the reams of evidence that it doesn’t work. Between 1993 and 2017, the 100 largest urbanized areas in the United States spent more than $500 billion adding new freeways or expanding existing ones. In those same cities, congestion increased by 144 percent, significantly outpacing population growth. “I think traffic engineers tend to think traffic is like a liquid. If the pipes aren’t big enough, then it gets plugged up and overflows,” says Robert Goodspeed, a professor of urban planning at the University of Michigan. “The solution is building bigger pipes. But all of the evidence says that that’s not true, that instead [traffic] is much more like a gas, meaning the volume of traffic congestion will expand to take up the capacity allowed.”

If traffic can expand, it can also contract. Advocates in Texas are at the epicenter of a national movement asking: What if, instead of building our aging roads back wider and higher—doubling down on the displacement that began in the 1950s and the climate consequences unfolding now—we removed those highways altogether? What if we restored the scarred, paved-over land they inhabit and gave it back to the communities it was taken from?

On a breezy, warm day in April, State Representative Armando Walle appeared before the House Transportation Committee to introduce House Joint Resolution 109, a measure that would put to a public vote whether to allow for state highway funds to be spent on things other than roadways, including sidewalks, bike lanes, and public transportation. Dozens of Texans testified in support of the bill. About an hour into the hearing, Jack Finger, a member of the advocacy group Texans for Toll Free Highways, testified against the measure. “Do not take my gas tax dollars for the bus, nor for bike paths, nor for sidewalks,” he said. “The local municipalities can pay for their own. To me it smacks at a socialistic attempt to get me out of my vehicle.” HJR 109 was left pending in committee.

The idea that public transit is for socialists and that highways enable free-market capitalism pervades the state’s politics. According to Farm&City, a nonprofit that advocates for sustainable development across the state, Texas is one of only a few states in the country without dedicated state funding for public transportation in major metro areas. Over the past two decades, surveys have found that people who live in these urban areas, as 85 percent of Texans do, have consistently said they would prefer investments in public transit instead of bigger highways. Even the outgoing CEO of TxDOT, James Bass, said earlier this year that he’d like to see more investment in transit: “With the projected population and growth in the state of Texas, I think as we move forward in time, we’ll need to consider investment in additional modes.”

But the Legislature has refused. State law requires roughly 97 percent of TxDOT’s roughly $15 billion annual budget to be spent on roadways. For decades, Texas Republicans have contended that highways are the engine that powers the state’s economy. “Everything we’re doing for transportation infrastructure feeds into keeping Texas number one in the nation for economic development,” Abbott said in January.

It’s the same argument advanced by the Associated General Contractors of Texas (AGC), which represents 85 percent of the state’s highway contractors. Between January 2013 and December 2020, AGC contributed more than $2.5 million to Texas officeholders, most of that to powerful Republicans, and another $2.2 million to Texas Infrastructure Now, a pro-road-building political action committee, according to Texans for Public Justice. In that time span, the group donated $375,200 to Texans for Greg Abbott, $334,950 to Texans for Dan Patrick, and $303,100 to Senator Robert Nichols, the chair of the Senate Transportation Committee. Terry Canales, the Democratic chair of the House Transportation Committee, received just $4,000.

“As TxDOT considers how to rebuild I-35 through central Austin, we wonder, Why don’t they consider other modes?” says Bo McCarver, a community activist in East Austin who worked for TxDOT from 1980 to 1999. “Well, AGC is not going to let you. The Legislature’s not going to let you.” AGC did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

“TxDOT and AGC have formed a symbiotic relationship over the years,” writes Gary Scharrer, a former journalist turned AGC spokesperson, in his 2020 book, Connecting Texas: True Tales of the People Who Built Our Highways and Bridges. Doug Pitcock, the founder and CEO of Williams Brothers Construction, the company responsible for expanding Houston’s Katy Freeway to 26 lanes, told Scharrer that mass transit “is not a solution for solving the congestion problem on the highways. … In my opinion, you will never do away with cars.” Pitcock himself has donated nearly $5 million to Texas officeholders since 2013, according to the Texas Ethics Commission, with most of that going to Republican candidates or PACs.

The assertion that a Texan will always require a car is a self-fulfilling prophecy. In 1967, DeWitt Greer, the head of the Texas Highway Department—as TxDOT was known until 1975—said upon his retirement that mass transit was not the answer for Texas. “It would take a generation to break Texans of the comfortable and convenient habit of riding in the automobile. If we are to please the taxpayers,” he said, “then we must develop more adequate thoroughfares in the urban areas.”

Two generations later, the costs of that habit have come due.

Even as cars have become more fuel-efficient and electric vehicles have trickled into the market, greenhouse gas emissions from passenger vehicles have continued to climb. In Austin, the average driver emitted 12 percent more greenhouse gases in 2017 than they did in 1990, according to a New York Times analysis of road emission data. In Dallas-Fort Worth, the average driver emitted 27 percent more. “Suburban driving, including commuting, has been a major contributor to the expanding carbon footprint of urban areas,” the project’s lead researcher concluded.

In 2018, the last time TxDOT did an analysis of the greenhouse gases generated on its roads, it found that road emissions in Texas account for 0.48 percent of total worldwide carbon dioxide emissions, even as the state accounts for only 0.38 percent of the world’s population. Today, TxDOT insists that fixing congestion will help reduce emissions, arguing that cars run more efficiently at higher speeds, despite research that shows emissions are more closely tied to distance traveled. Meanwhile, taking public transit can reduce average greenhouse gas emissions per mile by half, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation—and cut your chances of dying or being seriously injured in a car crash by 90 percent, according to a study by the American Public Transportation Association.

In Round Rock, 20 miles from Lafleur’s home, a limestone brick wall edges a rolling green golf course tucked just west of Texas Highway 130. Behind the wall, two-story homes sprout along streets with names like Asher Blue Drive and Lady Swiss Lane. Polyethylene wrapping flaps in the wind as workers install roofing shingles and hammer in siding. Some homes have cars parked in driveways and plants spilling out of terra-cotta pots; others are still plywood skeletons.

In 2015, this area—traffic analysis zone (TAZ) 1797—had a population of 6,879, according to the Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (CAMPO). By 2045, the agency predicts the population will more than quadruple.

This projection doesn’t match the on-the-ground reality, says Cole Kitten, a planner in the City of Austin’s Transportation Department, because population growth is not linear. Some TAZs may have experienced rapid growth over the past decade as subdivisions were built on vacant land and people moved into new homes, but once those areas are built out, that growth should effectively get shut off. In March 2020, Kitten wrote an email to Ann Kitchen, a member of Austin’s city council and the vice-chair of CAMPO’s transportation policy board, to express his concerns. “This is not how demographic forecasting is done, anywhere,” he wrote.

Most urban areas are required under federal law to create regional planning organizations that study and predict future travel demand based on population growth. These plans become the basis for how TxDOT prioritizes projects and allocates funding across Texas. “We do build to projections. So we look forward to say, ‘OK, what do we anticipate the traffic will be in so many years?’” says Hodges, the TxDOT spokesperson. “We are trying to accommodate what is going to be there.”

But the act of predicting itself can shape the future. “A lot of people want to avoid the conversation of what is desirable and they just say, ‘Well, the number says this, and so we’ve got to accommodate it,’” says University of Michigan professor Robert Goodspeed. He calls this “colonizing the future.” If you plan for a future of car-centric sprawl, that’s what you’ll get. If you don’t build bus lanes or light rail stations, people won’t take public transit. If you don’t build enough housing to enable people like Lafleur to buy homes near their jobs, those people will climb in their cars and drive until they can afford one.

In 2019, an outside consulting firm hired by TxDOT for a different project looked at CAMPO’s long-term population growth rates and registered similar concerns as Kitten, concluding the growth rates were “outside the range used in most studies.” If that population growth didn’t materialize, the company wrote, “the roadway configuration could be overdesigned at a higher monetary cost, with more disruption to the local community, and potentially include a greater environmental impact.”

These concerns went unaddressed. CAMPO formally adopted the 2045 plan in May of last year, projecting significant population growth in Williamson County, where Round Rock and Cedar Park are located. Now, Kitten worries the same flawed growth models will be used to plan the I-35 corridor. If TxDOT engineers use CAMPO’s population growth forecasts, as they’ve said they will, they might conclude that a much wider highway in Austin is required to accommodate the booming population growth projected in Williamson County—even if the only way to make that growth materialize is by building a bigger highway.

Adam Greenfield powers up a blue decibel meter the size of a cell phone. Greenfield, a longtime activist and the founder of a grassroots campaign called Rethink35, stands on a hill overlooking Interstate 35, where East Ninth Street ends at a guardrail and tumbles sharply down a grassy slope toward the highway. It’s a brisk January morning, and Austin’s downtown glistens in a spread of glass and steel, a dozen cranes perched above. Traffic roars below, and the screen flickers as the foam-covered microphone registers a reading: 82. Anything over 85 decibels can cause permanent hearing damage, Greenfield says—one of many ways the highway harms people who live nearby. He makes note of the recording, part of his campaign to turn I-35 back into a boulevard.

What is now I-35 was once East Avenue, a four-lane boulevard split by a wide grassy median dotted with impeccably manicured bushes and trees. Families picnicked in the shade between the northbound and soundbound lanes. In 1943, the Austin Chamber of Commerce released a film welcoming newcomers to what it called “the Friendly City.” Among scenes of Austin’s treasures—Congress Avenue, the University of Texas, the 340-acre Zilker Park—the video included a shot of East Avenue. “Would you believe this was once a cow pasture?” the narrator intones with a Texas twang. “Under a program of civic improvement, it was changed into East Avenue, a pleasure to the eye and a major north-south thoroughfare.” A stone-lined drainage ditch crosses the foreground; in the background is a row of red-brick buildings. Two skinny-limbed kids sprint across the frame.

In 1928, the city’s first comprehensive plan created a 6-square-mile “Negro District” on the east side of town, effectively prohibiting Black people from living west of East Avenue. Starting in the 1950s, the construction of I-35 consumed the boulevard, demolishing hundreds of homes and businesses and erecting a physical barrier between neighborhoods of color and the heart of the city. There is essentially no urban highway in the United States that didn’t unleash similar violence on Black and Hispanic people so that white people could get home faster. Even before the Federal-Aid Highway Act passed in 1956, highway builders and car manufacturers promised not only to revitalize downtowns by connecting suburban commuters to city centers, but also to “displace outmoded business sections and undesirable slum areas,” according to a General Motors promotional video made in 1939. According to Eric Avila, an urban planning professor at the University of California Los Angeles, between 1956 and 1966, highway construction consumed 37,000 units of housing in cities across the country annually, displacing hundreds of thousands of people.

Greenfield wants TxDOT to tear down I-35 through central Austin and replace it with a modernized version of East Avenue: a boulevard with space for cars but also bike paths and bus lanes and wide sidewalks, lined with apartments and offices and restaurants, trees shading courtyard cafes. His proposal is a more radical version of a campaign called Reconnect Austin, which would have TxDOT tear down the elevated decks that clatter over the city, depress the highway belowground from Lady Bird Lake to Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, and cover most of it with a boulevard and parks, stitched into the street grid. Heyden Black Walker, an architect and urban planner who leads Reconnect Austin, says the city could reclaim nearly 74 acres of land currently occupied by frontage roads and highway barriers where it could build thousands of units of affordable housing near jobs, thus removing some of the demand on the highway.

Removing I-35 “is a chance to right a very, very grievous wrong,” Greenfield says. “I feel very mixed when I look at it. I feel the full force of its social, environmental, economic impacts, which are dire. But then I look at it and I’m like, wow. This could be more incredible than any of us could ever fathom.”

The idea of highway removal has been around almost as long as highways themselves. In the mid-1950s, the California Highway Commission started construction on Interstate 480, known as the Embarcadero Freeway, to connect the Bay Bridge on San Francisco’s east side with the Golden Gate Bridge. More than a mile was built, obstructing views of the bay and cutting off Telegraph Hill from the waterfront. In 1959, after thousands of people organized, San Francisco’s board of supervisors voted to cancel further construction, citing “the demolition of homes, the destruction of residential areas, [and] the forced uprooting and relocation of individuals, families, and business enterprises.” In the mid-1980s, local leaders proposed tearing it down; voters rejected the proposal, convinced that it would cause gridlock. Then, on October 17, 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake rocked the city, damaging the highway structure beyond repair. As city leaders dithered about what to do, drivers simply maneuvered around the highway and got where they were going without noticeable delays. Bus ridership increased 15 percent. Public opinion turned—maybe the highway wasn’t so necessary after all. Demolition was completed in 1993; by 2002, the space was transformed into an airy, populated, palm tree-lined boulevard, surrounded by apartments, restaurants, and offices.

In 2004, Milwaukee Mayor John Norquist, who had successfully campaigned to remove a mile-long spur of the elevated Park East Freeway in his hometown, stepped down to lead a nonprofit called Congress for New Urbanism (CNU), where he began a campaign for the removal of urban highways across the country. By 2020, CNU had active campaigns in nearly 30 cities, from Pasadena, California, to Syracuse, New York. Some campaigns call for full demolition, replacing highways with boulevards like in San Francisco. Others propose a vision like Reconnect Austin—depressing a highway and covering it with a park at street level, as Dallas did over the Woodall Rodgers Freeway in 2012. Although more than a dozen highways have since been removed, the idea has remained mostly an aspirational one, promulgated by urbanist nonprofits like CNU and the occasional mayor.

That is until President Joe Biden appointed Pete Buttigieg to lead the U.S. Department of Transportation. Seemingly overnight, the harms wrought by urban highways became mainstream news. In January, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer introduced his sweeping Economic Justice Act, with $10 billion of funding specifically earmarked for highway removal or retrofit, and a directive for agencies “to focus on improvements that will benefit the populations impacted by or previously displaced by the infrastructural barrier.” At the end of March, Biden doubled down on this pledge when he unveiled a $2 trillion infrastructure plan that included a proposed $20 billion to “redress historic inequities and build the future of transportation infrastructure.” That same month, the Federal Highway Administration intervened to stop the expansion of I-45 in Houston, citing civil rights concerns.

When you’re in a car, I-345 is a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it highway. It’s a quick swoosh through downtown Dallas, connecting I-45 with U.S. Highway 75. You don’t even see a sign for I-345 until you’re on it. By that time, you’re halfway through the 1.4-mile stretch, suspended 25 feet in the air by concrete. A billboard welcomes you to the historic neighborhood of Deep Ellum as you speed past. Traveling at 70 miles per hour, your experience of I-345 lasts for less than a minute.

Down on the ground, however, the experience of the highway is generational. Deep Ellum was originally settled by former slaves after the Civil War and became the cultural heart of Black Dallas. Businesses like La Conga Cafe and Gypsy Tea Room formed the backbone of a thriving Black community. Dozens of theaters and clubs along Elm Street would launch the careers of jazz and blues musicians in the 1920s and 1930s. As European immigrants settled in the neighborhood and opened grocery stores and pawnshops, Deep Ellum became one of the city’s few integrated communities. But starting in the 1950s, urban renewal came for Deep Ellum. By 1973, the elevated highway cut the neighborhood in half and consumed 54 city blocks, including the historic Harlem Theater in the heart of the community. By the late 1970s, most businesses had shuttered, and the neighborhood slowly emptied out.

In 2002, when Patrick Kennedy moved to Dallas, fresh with a degree in landscape architecture from Pennsylvania State University, he rented a place in Deep Ellum and walked to work. He’d wanted to live near his new job downtown, so every day, he’d walk along cracked sidewalks, past public storage facilities, boarded-up buildings, and surface parking lots, the black asphalt radiating heat in the summer. He’d walk under I-345, the canopy casting a long shadow blocks beyond its physical reach. And he’d wonder: Couldn’t this be something better?

Almost a decade later, the City of Dallas published a master plan for downtown that concluded that the inner highway loop was “a significant barrier to surrounding neighborhoods” but that fixing it was a “long-term and expensive proposition.” TxDOT had announced plans to rebuild every other highway that encircled downtown, save for I-345. Kennedy and a friend studied the traffic flows on the eastern edge of the city and saw that, while the highway was often congested during peak hours, the city streets that surrounded it sat empty. The highway had scrambled the local grid, disrupting the north-south flow of streets, which were built to carry much more traffic than they did.

“So we said, ‘OK, hypothetically, what if we just remove the thing?’” Kennedy says. They mapped the highway’s right of way and the underdeveloped land that surrounded it and found that it affected hundreds of acres representing billions of dollars in developable land and millions in property tax revenue, in a city that desperately needed the money to fund basic services like schools and sewage. “I had to pitch it to the power structure of Dallas. What do they care about? They care about money,” Kennedy says. The financial pitch was the Trojan horse for other, harder-to-quantify benefits, he says—equity, environment, quality of life.

Kennedy got the ear of an unconventional member of the Texas Transportation Commission, Victor Vandergriff, who commissioned a 2016 study called CityMap that, for the first time in the agency’s history, included the full removal of an elevated highway as an option. TxDOT engineers talked to hundreds of people across the city, and public feedback was decisive: People didn’t care all that much about congestion. They cared a lot about community and connectivity and parks and housing. Removing I-345, the study found, would increase congestion delays on nearby thoroughfares by just 1 minute.

CityMap was unlike any document TxDOT had ever produced, representing an inflection point in how some TxDOT engineers, at least in Dallas, considered their work. “We’re not here to move cars,” says Mo Bur, TxDOT’s Dallas district engineer. “We’re here to have a project that will address all kinds of transportation. And then, once we leave, what does it do to the community that the highway went through?”

According to a 2021 report, 377 acres of land in the core of the ninth-most-populous city in the country had either been subsumed by I-345 or depressed by its presence. This represented more than $9 billion in developable land and $255 million in total annual property tax revenue. Removing the highway could create the capacity for 59,000 new jobs and as many as 26,000 housing units, the report found. For years, job growth has clustered in the suburbs north of Dallas while most of the affordable housing has stayed south of I-30. “The typical response has been, ‘Well, how do we help low-income people drive and access jobs that are going increasingly farther to the north?’” says Kennedy, who also serves on the board of Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART). “My response has been, ‘Why don’t we bring housing and jobs closer together and reorient downtown as the center of job growth?’”

The business community got on board immediately. “Buy land,” Mark Twain famously wrote. “They aren’t making it anymore.” Removing I-345 would do just that—make land, and very valuable land at that. But who would profit from this new land, ripped from a thriving Black community a generation before?

In St. Paul, Minnesota, the construction of I-94 through a predominantly Black neighborhood called Rondo claimed more than 700 homes. In 2020, a nonprofit called Reconnect Rondo calculated that the loss of that home equity represented at least $157 million of generational wealth taken from Black families—the equivalent of 4,800 four-year college degrees. Policies to repair the harms wrought by a highway like I-345, which disproportionately impacted Black families and businesses, cannot be race-neutral, says Jerry Hawkins, the executive director of Dallas Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation. Removing the highway is great, he says, “but for who?”

He’s skeptical that the land created by removing the highway will actually help the people—or their descendants—who were so violently displaced by its construction. “There are a lot of larger conversations in urban development about what reparations would look like,” says Ben Crowther, a program manager for CNU’s Highways to Boulevards program. “As we think about removing things like highways, what are ways that we could provide benefits to community members for whom the highway was a barrier—who are no longer there?”

Amy Stelly, an architect and the founder of the Claiborne Avenue Alliance in New Orleans, is one of many advocates pushing to put the land liberated by a highway removal into a community land trust, which separates the ownership of a structure—like a single-family home or an apartment complex—from the land beneath it, to create permanently affordable housing. “What a land trust must do now is put that affordable housing back so that the people who make New Orleans New Orleans can move back into the neighborhood,” says Stelly, who is Black and grew up within blocks of the highway she’s fighting to tear down.

Because of a 1995 state law governing the sale of highway right of ways, the City of Dallas—or a nonprofit community land trust—would have to buy any “surplus” land created by the removal of I-345 from TxDOT at fair market value, likely out of reach for anyone but for-profit developers. “The majority is going to be folks who have money and opportunity to develop it. That’s definitely not Black and brown folks,” Hawkins says. But that’s where federal funding—the $10 billion earmarked by Senator Schumer in his Economic Justice Act, the $20 billion in Biden’s American Jobs Plan—could potentially be transformative, putting that land back into community control. “Thankfully, highway removal is glamorous now,” Stelly says.

Like so many others, Robin Lafleur was grounded at home for most of 2020. In some ways, it was a relief. “It was refreshing to not be on the road in all of the hustle and bustle of I-35,” she says—a gift to get three hours of her day back. In November, she started commuting again, three to four days a week, 50 miles a day. She looked into taking transit, hoping she would be able to work on the way, but it would have added two hours to her round-trip journey.

In 2013, the Texas A&M Transportation Institute modeled seven scenarios to solve congestion on I-35 as Austin boomed. “Congestion will be severe even if a substantial amount of roadway capacity (typically as lanes) is added,” the study concluded, recommending that planners focus on managing demand on the highway—shifting 40 percent of commuters to work-from-home, creating virtual classes for university students, replacing in-person retail shopping with online shopping.

In March 2020, those recommendations became reality. After stay-at-home orders for COVID-19 went into effect, vehicle trips dropped by roughly 40 percent on I-35 and congestion all but disappeared. “One of the things about the virus that I think is so important is that up until now that’s been a theoretical model, which might have been wrong,” says Heyden Black Walker of Reconnect Austin. In May 2020, anyone could go for a drive and see it for themselves—the fact that you don’t have to get rid of all cars to solve most traffic. “I think we should use the pandemic as a time to really learn and reevaluate what we’re doing.”

In late 2020, TxDOT released renderings for I-35 that showed a 20-lane highway, including frontage roads, an increase of eight lanes. “To spend $7 or $8 billion dollars on a project like that, to me, just doesn’t make sense when a better solution would be to figure out a way to improve commuter options, getting us from one spot to another in a safer vehicle,” Lafleur says. “In a bus or on a train where you don’t have to worry about people that aren’t paying attention while they’re driving.” Lafleur loves her job, helping people find homes in Austin. She just hates getting there.