The Strangers Next Door

How Amarillo became a safe haven from violence across the world — and Ground Zero in the backlash against refugees.

A version of this story ran in the April 2016 issue.

Alphonse Kayiranga wasn’t sure what to expect from his new home. His family had been killed in the Rwandan civil war, and he’d spent six years in Kenya waiting for the United Nations to process his refugee claim. He was prepared to be open-minded. Still, with each connecting flight, the planes got smaller. He’d assumed that being sent to the United States meant he’d live in a big city like Nairobi, but looking out his window at the crops and open plains around Amarillo, he let a new image form in his mind. He figured he was destined to be a farmworker and resolved to make the best of it, picturing himself in overalls and a big hat. All he could say for certain, he recalls, was “I’m going somewhere, but I know I will live, I will have a life.”

Musaab al Khayatt suited up with American troops during the Iraq War, providing translation and support for civil affairs missions. After the troops left, Baghdad wasn’t safe for him because of the work he’d done. People mailed threatening letters with bullets tucked inside. One day, he left work and someone tailed him home, shooting and ramming his car from behind. Then a stranger arrived with the clearest warning yet: Leave soon or be killed. “I’m glad they gave me time,” he says, “because usually they don’t do that.” He turned up at the U.S. Embassy asking for a way out. After two years in Jordan waiting to be processed, he and his family arrived in Amarillo in 2008.

Thuraya Lohony fled Iraq with her husband in 1996. She’d been a middle school teacher and her husband worked on a U.S.-backed rebuilding effort in Kurdistan after the first Gulf War. When the U.S. State Department gave notice that their home was no longer safe, and that they’d be resettled in the United States, they had just a few days’ notice. They left their house with one piece of luggage and flew to Guam, spent four months there being interviewed, then flew to their new home. “I said, ‘What is this place?’” she recalls. “Oh my god, I never heard about Amarillo.” They had no family and no job prospects, but she says they were excited to start over together. Being Kurdish and growing up in Iraq, Lohony says, she was already acquainted with statelessness. Now, after 20 years in Amarillo, she says, “I feel like this is my home. This is my family. This is my country.”

For decades, Amarillo has been the happy ending to thousands of stories like these. People have come from Cuba, Vietnam, Somalia and Burma to start new homes in a place they never knew existed. They arrive in Amarillo, as the George Strait song goes, with just what they’ve got on. But after a couple of years in Texas schools, children with no formal education manage to pass standardized tests. People who’d been doctors and teachers go back to school here and begin new practices. They open restaurants and shops, buy houses and cars. Some, like Lohony, al Khayatt and Kayiranga, find work at refugee placement services and help new arrivals adjust to the sudden transition. The city offers an opportunity not just for a better life, but for life itself. As American-dream stories go, it doesn’t get much better than that.

But lately, a new story about Amarillo’s refugees has taken hold, one that’s not so idyllic. Local residents, including the city’s mayor, have begun complaining that Amarillo has taken on too many refugees. They say dealing with so many different languages is dragging down the schools and maddening the 911 operators. In 2014, Congressman Mac Thornberry told the Texas Tribune that one refugee was caught hunting on someone else’s private land.

Rumors spread that refugees were forming shadow governments and electing their own leaders. Anecdotes such as these were passed around the state Capitol in 2015 and employed to pass new laws aimed at limiting refugee placement. Conservative message boards seized on the horror stories, and suddenly, as the nation considered its duty to share in the resettlement of those displaced in the Syrian civil war, Amarillo became a cautionary tale: Let in too many Muslims and this is what you get.

“Amarillo is building Muslim ‘ghettos,’” the conservative news site Watchdog.org baldly asserted in a January report. “Amarillo now sports the dubious title of having the country’s highest ratio of refugees from Middle East nations,” Breitbart Texas reported, wrongly. “It is about Sharia Law!” one popular refugee critic warned. “This is how it begins.”

***

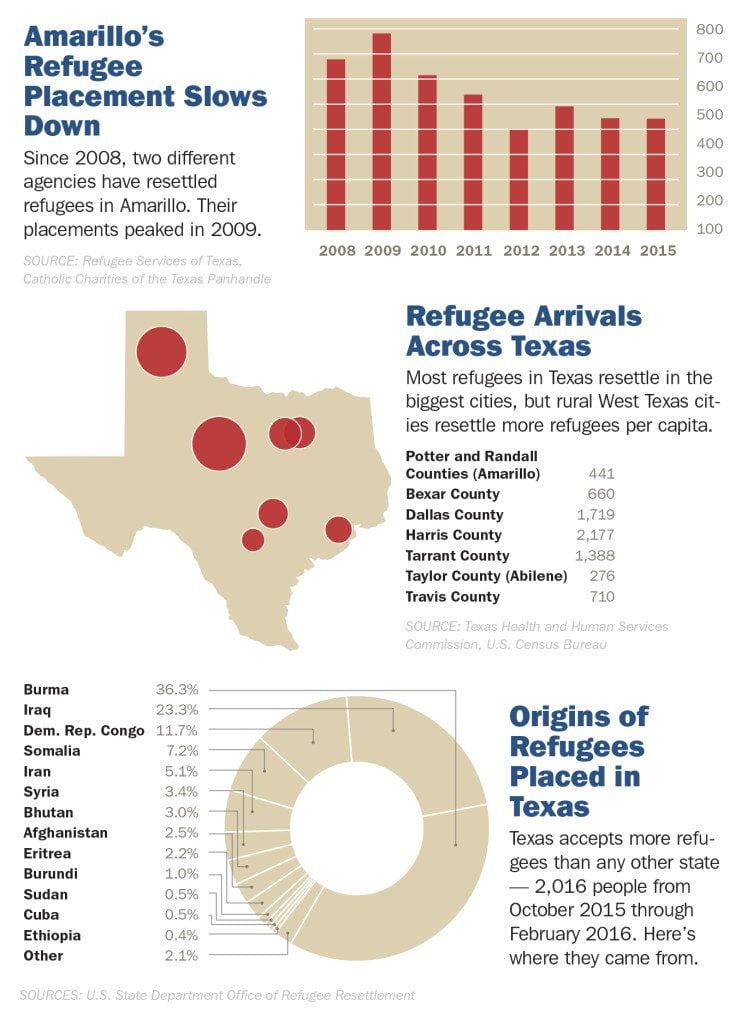

Refugee support in Amarillo dates to the 1960s, when Cubans arrived and local Catholic charities responded with open arms. A few years later, they helped a new wave of refugees settle from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia after the Vietnam War. Since then, the city has taken in a steady stream of refugees from all over the world, their origins shifting as global conflicts heat up and cool down. Only Texas’ biggest cities have accepted more refugees than Amarillo. Per capita, no city in Texas has taken in more. (By this measure, Amarillo was still just 41st nationwide in 2014, with 256 refugees for every 100,000 residents. Stone Mountain, Georgia, had 11,037.)

Today, with funding from the U.S. State Department, Catholic Charities of the Texas Panhandle arranges housing, furniture and food for new arrivals, along with ESL classes, help enrolling in medical benefits, and job counseling during refugees’ first few months in the country. The Texas Health and Human Services Commission provides limited support beyond those first three months, but after that, refugees are generally on their own. It’s a point of pride among resettlement workers that so many clients become selfsufficient so quickly. Like other resettlement hot spots such as St. Cloud, Minnesota, or Sacramento, Amarillo seems like an unlikely place to meet a thriving expatriate community from Southeast Asia or Central Africa. But it’s a sensible destination for people starting over, with cheap rent, plenty of jobs and a network of former refugees.

People have come from Cuba, Vietnam, Somalia and Burma to start new homes in a place they never knew existed. They arrive in Amarillo, as the George Strait song goes, with just what they’ve got on.

In 2008, the new demand for services prompted Refugee Services of Texas, which has branches across the state, to open an office in Amarillo. Many refugees who were placed elsewhere were moving to Amarillo as soon as they landed. Refugee Services also began accepting hundreds more direct placements in Amarillo each year, duplicating the work Catholic Charities had handled on its own for decades.

In a city of fewer than 200,000 people, refugees were arriving in numbers great enough to be noticed, and that’s when the backlash began. In 2011, the city’s new mayor, a car dealer named Paul Harpole, began arguing that Amarillo’s disproportionate share of refugees was taking a toll, particularly on police and 911 dispatchers who struggled with language barriers. In an email obtained by the Observer through an open records request, Harpole explained to a man in nearby Canyon that refugees shouldn’t cluster in Amarillo “simply because we have a big heart and tradition of agencies here that settle them.”

Harpole, who did not respond to interview requests from the Observer, began lobbying the Legislature for greater local control over refugee placements. Harpole, Thornberry and state Senator Kel Seliger began demanding answers from the U.S. State Department about how refugees are screened and relocated. In response, State Department officials visited Amarillo to meet with them and the resettlement groups. Cutting down on new settlements would cost the groups much of their federal funding, but Catholic Charities Director Nancy Koons says they didn’t have much choice.

“Do they want to assimilate and become citizens that adhere and believe in and support our Constitution and our way of life? Or do they want to maintain their way of life?”

***

Late last year, a series of events around the world brought harsh new attention to the country’s refugee policy. First came the wave of migration into Europe from Syria’s civil war. Then came President Obama’s announcement that the United States would raise its quotas for Syrian refugees. Then came the Paris attacks in November and the San Bernardino shootings in December, each of which stoked fears about militant Muslims infiltrating the immigration system. Amarillo’s leaders were already on the record with refugee concerns. It didn’t take too much work for conspiracy writers to fashion the city as a harbinger of the globalist dystopia America was about to become.

Refugee placement policy went from local budget issue to existential threat in a matter of weeks. In January, Watchdog.org dispatched reporter Kenric Ward to interview Harpole, who gamely shared anecdotes about the city’s Muslim “ghettos” and his shock at learning “that rival tribes — slaves and masters — were being settled together.” Harpole has since said he was misquoted. He sat for an interview with local ABC affiliate KVII to set the record straight, telling them, “I have always felt that they’ve been a big part and a good part of our community.” He still believed that the concentration of refugees was hurting the city, but calling Amarillo a breeding ground for radical anti-American thought? Now that was going too far.

Harpole’s clarification did little to slow the sensational story’s spread on conservative news sites. Amarillo became the “city overrun with warring tribes (and we’re not just talking Crips and Bloods),” according to one. Breitbart Texas offered its own take on the Watchdog.org story, accompanied by a photo of uniformed Syrian schoolchildren staring uneasily into the camera. The news site 100PercentFedUp.com featured a former Amarillo resident, Karen Sherman, who’d been sharing Panhandle horror stories outside a courthouse in Missoula, Montana. “SHOCKING! ONE WOMAN’S STORY Of The Muslim Invasion In Her American Town,” blared the headline. “She claimed the refugees have previously been given preferential treatment ahead of citizens in receiving benefits,” the story read. “Please note that assimilation is not numero uno for these folks!” The story quoted Sherman directly with an even more shocking assertion: “Now they’re expecting us to give them cars.”

Fabian Talamante, who heads Refugee Services’ Amarillo office, says the folks he resettles do not, in fact, get cars. They get a bus map. Silly as the right-wing panic may sound, he says, it still hurts. “If you’re a refugee and you’ve seen some of those articles on TV, how would that make you feel?” he asks. Talamante can sympathize. “I grew up in racism,” he says. “I used to be called a wetback. ‘Go back to Mexico, beaner.’ And it makes you want to stay in your own neighborhood. That’s where you feel safe.”

He says one woman told him last fall that she was leaving town. When he asked why, she told him, “They don’t want us here.” Al Khayatt, a career counselor for Refugee Services, accompanied Talamante to a community meeting at the height of the panic. He stood up and told the crowd about volunteering to help U.S. soldiers, about their close calls with roadside bombs and the harried sprints back to their base. “I said, ‘I need everybody to tell me, did I have to be here or not? Y’all tell me. If I’m not, then I will leave.’ And they say, ‘Of course’ and ‘Thank you for your service.’ I said, ‘Each refugee has a different story. I know some people probably with worse stories than I’m telling you.’”

In October, a man named Cody Nevels announced on Facebook that he’d be leading a local anti-Muslim protest to coincide with Global Rally for Humanity events across the country. “We are everywhere and we want our country back!” the event page declared, over a skull patterned with an American flag turned backwards. The group planned to rally outside the city’s Khursheed Unissa Community Center, which has been a center of Muslim life in Amarillo for nearly 20 years. It has also long been the subject of paranoid speculation that it’s tied to the University of Islam Sultan Sharif Ali (UNISSA) in Brunei, which is, in turn, rumored to be a breeding ground for radical Islam. Local conservative activist Tom Lehner has suggested the center is part of the Obama administration’s effort to aid Muslim infiltration along key points in the nation’s highway network.

Ahead of that rally, Talamante says, the mood got so fraught that one Somali caseworker refused to leave her house and al Khayatt showed up to work in a bulletproof vest. When the time for the protest came, though, “Those guys never showed up,” Talamante says. Instead, the scene was all church groups and other refugee supporters. “And I cried,” he says. “What an amazing community.”

The mood is less tense today, but there are still people in town hoping to limit refugee placements even more. In February I met one of them, a retiree from Temple named William Sumerford, who serves on the board of the Amarillo Tea Party. Sitting in a coffee shop inside a United Supermarket on the city’s northwest side, Sumerford says his group doesn’t want an all-out ban on refugees, only to correct a statewide imbalance. Sumerford has agreed to meet for a few minutes before he’s due for work at a GOP primary polling place. “Average of the state of Texas would be what’s fair for Amarillo,” he says. “That means no more refugees in Amarillo for years.”

The signs of strain are there if you know where to look, he says. The county’s law enforcement budget is more than Sumerford would like, and he believes there’s a refugee connection to that too. “I’m not saying all these people are refugees, obviously, but it is a factor.” (In an email to a resident worried about crime, Harpole pushed back on this concern. “We do not have a crime problem related to refugees,” he wrote.) Based on stories Sumerford has heard around town, he says American policing simply isn’t compatible with some refugees’ cultural norms. “These people have different kinds of governance,” he says. “Is that the kind of governance they would like to have? Do they want to assimilate and become citizens that adhere and believe in and support our Constitution and our way of life? Or do they want to maintain their way of life?”

He adds: “We don’t need to have a civil war about it, but we need to be reasonable. We need to be responsible. And we need to take some action.”

***

On a Friday morning at Margaret Wills Elementary School in central Amarillo, students parade single-file down the hallway, picture books hugged tight against their chests. In one dark pre-K classroom, a group of students sit watching a video about vowel sounds set to the Batman TV series theme song. Their principal, Chris Altman, tells me only one of them speaks English. In a fourth-grade classroom, kids sit around a table with their teacher learning about the sounds cows and sheep make and what they do on the farm — the sort of thing that standardized test questions presume all students know, but many of these students do not.

Altman says around 40 percent of the school’s 600 students are ESL learners, and teaching them forces teachers to abandon their assumptions and get creative. It’s not for everyone, she says, but many of her teachers wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. (Shanna Peeples, last year’s National Teacher of the Year, works at nearby Palo Duro High School and has credited her refugee students with shaping her approach to the job.) Altman says she’s learned more in her four years at Wills than in the rest of her 30-year career before she arrived.

Wills is one of a few schools in the Amarillo Independent School District with a large refugee population. Resettlement groups tend to place people in the same few apartment complexes, which means their children enroll in the same few schools. Many of the students live in the apartments just across the street, white duplexes and beige three-story complexes that look like any other neighborhood in town, except for the occasional line of shoes outside a front door.

Just before the school day ends, parents begin crossing the street and mingling beneath a large tree in front of Wills’ brick facade. Altman says the school is another layer of support for the whole family — there are afterschool and summer classes for students who need extra English instruction, and adult language classes for parents. Until last year, the school had an extra grant to support that work, but now, she says, they get by with the same funding as any school its size. There’s no extra refugee-education budget for the school.

In these classrooms, Altman says, teachers make sure students learn that diversity is a strength. They’re encouraged to discuss the differences in their home lives. “Our differences can either be our ruin or a source of strength for us,” Altman says. “That’s not what all of them hear at home, but here we talk about [how] the amazing thing about our school is you get to go to school with students from all over the world.”

In a trendy coffee shop in downtown Amarillo, one of the new businesses that are slowly filling the storefronts of the city’s old brick high rises, I meet Brady Clark, Jacob Breeden and Andrew DeJesse, who have a scheme to encourage that global spirit outside classrooms, and into the city’s broader culture. Clark is a pastor and Breeden is a sculptor and painter; both grew up in Amarillo. Neither fit in during high school — Breeden’s sensibility was too artsy and Clark was a punk — and left for bigger cities after graduation. Both have returned home, in part, for the same reasons so many refugees come here: The cost of living is low and the small city is full of opportunity. (At age 39, Breeden already owns his own gallery downtown.) They’re also here, they say, because Amarillo is more diverse than it was in their high school years, thanks in part to refugee resettlement.

Clark says his outreach work has shown him that Amarillo’s biggest challenges are the result of generational poverty. But the arrival of new refugee groups presents a much simpler explanation: If things are getting worse, it must be these newcomers’ fault. “You can substitute whoever you want for the ‘they.’ It could be Mexicans, it could be illegal immigrants, it could be refugees, it could be the Irish, who knows,” Clark says. “The problem’s deeper, but we don’t want to look at that. We want to scapegoat.”

DeJesse, a New Jersey native whose wife grew up here, is one of the Army’s “Monuments Men,” charged with protecting cultural artifacts in war zones. After serving in Afghanistan, he saw that the cultural heritage he’d preserved overseas was being ignored or even resented by many in town. The three of them have started what they call a “collective heritage lab.” They’re soliciting writing, visual art and performance work from former refugees, to form the basis for a series of cultural events. Their goal is to showcase former refugees’ perspectives on their adoptive home, and in doing so, show how resettlement has enriched the city’s culture — to move past a debate over the cost of schools or police. “The narrative about how they’re a burden is the wrong narrative,” DeJesse says.

One after another, the people I spoke with in Amarillo seemed to feel that they’d been burned by those stories about the refugee invasion, that their city had been twisted to look like some place they didn’t recognize. The former refugees in town got the worst of it, of course. “I was really surprised,” Lohony says. “For 19 years, I never had any problems.” There’s no telling when another incident will inflame anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant or anti-refugee sentiments again, when some other city will be held up to illustrate the dangers of being too welcoming. For now, at least, that spotlight has left Amarillo, and the refugees who’ve made it home are still there, adjusting to their new lives.

Lohony will graduate this spring with a master’s in education from West Texas A&M. Like other refugees she works with, she’s been enrolled in night classes while she works, building to another career — in this case, the career she had before she left Iraq. She says she hasn’t decided whether she’ll leave Catholic Charities, but if she does she’ll take comfort from something she has learned after years of watching people arrive in a strange place, ready to embrace a new future. It’s a message she says she spoke about to folks in town in the last few months, when the closed-mindedness and xenophobia seemed at its worst: “Everybody can change. Everybody can adapt.”