The Symphony Comes to South Dallas

Music education and enrichment opportunities are scarce in my neighborhood, but the Dallas Symphony aims to bridge the gap.

She is growing a cosmic garden, she is one of the fates stretching a string of life before her, she is Moses parting the sea before turning to bring the waves down on Pharaoh. These are some of the lines I wrote in my notebook during a Dallas Symphony Orchestra performance almost a year ago as I sat spellbound by the conductor.

Though contemporary classical is my favorite genre of music, I didn’t leave my house expecting a spiritual experience on a date night. My tears surprised me—and then, looking around, I saw few faces like mine. Perhaps this paucity of black and brown attendees was unique to my experience that single night, but it’s doubtful. Even onstage, the symphony fails to attract much diversity: according to the League of American Orchestras, black and Latinx musicians comprise only 2 and 2.5 percent, respectively, of U.S. orchestras.

If you’ve hung out in the Dallas art scene for any length of time, you’ve probably heard the phrase “That’s so Dallas.” In this context, the expression refers to the way businesses and institutions in the city fail to engage local communities.

Take Decolonize Dallas, in which the city asked local artists of color to create works based on the neighborhoods they had ties to. The day after the pieces were installed, the city took them down for calling attention to gentrification and West Dallas’ affordable housing crisis. The art was only reinstated after the project’s curators made public their refusal to tolerate such censorship quietly. So Dallas.

It’s also So Dallas to stroll by The Epic—a mixed-use shopping/dining/hotel-palooza set to open soon—and see how developers have stolen the glow from the landmark Knights of Pythias temple and transformed it into a nondescript shell of its former self. Each time I drive by and see brown brick where murky white paint once rose into the sky, I think of how the soul of William Sidney Pittman might feel knowing the building he designed to be the center of black commerce in the city will now isolate the community it once served.

Enter Kim Noltemy, who in January 2018 became the first woman to lead the Dallas Symphony as president and CEO. Noltemy has designed programs to bring classical music to a younger generation and to expand the symphony’s reach beyond the glassy curves of the Meyerson Center. One of her key achievements is the Southern Dallas Residency Program, a 10-year commitment to make the symphony more accessible to residents of South Dallas, via instrument drives, music education programs, and community concerts.

Perhaps this paucity of black and brown attendees was unique to my experience that single night, but it’s doubtful.

Music enrichment opportunities in this part of the city can be as scarce as basic resources. Noltemy aims to make both music and the orchestra more accessible to South Dallas residents via three objectives: providing instruments and instruction to kids in South Dallas, creating opportunities for symphony musicians to perform there, and encouraging collaborations between symphony musicians and musicians in the community.

In January, the program was launched with an instrument drive and concert. The talent of Young Strings musicians—underrepresented youth who play string instruments—made me cry in awe. It also included a multigenre performance with me; Jessica Garland, the symphony’s community liaison; and Nicolas Tsolainos, longtime principal bassist. My improv poetry about spring and growth in the midst of climate change and systemic oppression flowed against the tenderness of Jess’ harp and the thunder of Tsolainos’ bass. After our performance, Garland invited children from the audience onstage for a quick harp lesson.

“I hope that this will help give kids in Southern Dallas an opportunity to get involved in something that they would otherwise not have had to get the chance to do,” Noltemy said. “For some it may become a lifelong love, and for others a way to make friends, learn more, and connect with new people.”

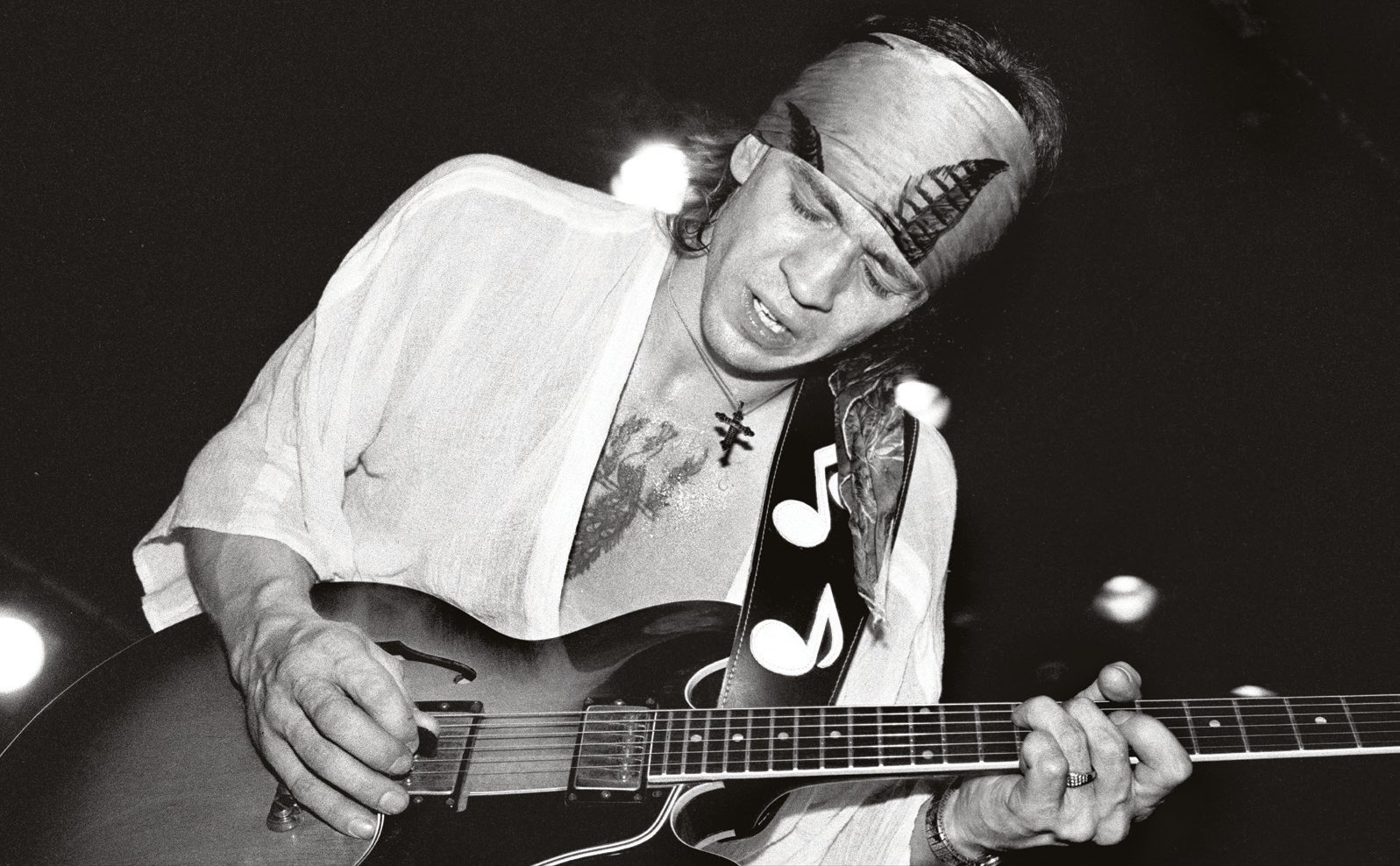

The Southern Residency Program’s next community event was in February, at Deep Vellum Books in Deep Ellum. This part of the city was founded by freedmen after the Civil War. Jazz and blues blossomed here in the 1920s—think Harlem of the South. Leadbelly, magician of the six-string guitar, spent his entire stint in Dallas calling Deep Vellum home. Now, books on topics ranging from sex work to the architecture of protests to the history of women in punk music line the shelves of the building he once called home. It was fitting for an event aimed at shaping the future of Dallas music to take place in a setting so important to its past.

Some of the best musicians in the city made an appearance, including Black Taffy, Midnight Opera, and the award-winning Poppy Xander. “When you place creative, caring people together you have the potential for all kinds of wonderful and unexpected impacts,” said Tsolainos. While the skill in the room was impressive, the numbers and reach left something to be desired. Most in attendance came from the experimental scene, but Dallas has a rich R&B and soul culture that would have added vibrancy to the event. The most obvious absence was that of more symphony musicians.

The most recent event this summer drew a sold-out crowd. On June 21, the symphony hosted Erykah Badu—who grew up in South Dallas before becoming a soul and experimental R&B star—at the Meyerson Center in the arts district.

Music enrichment opportunities in this part of the city can be as scarce as basic resources.

“The point in having Erykah Badu and the reason why it worked so well in this initiative is because she’s from South Dallas,” Garland said. “She shows what can happen being from this community …[and] the abundance of talent that can be found in South Dallas.”

The Southern Residency Program is named for the part of the city it serves, South Dallas, where my family lives amid an abundance of cardinals, stray dogs, and cement manufacturing plants. The city, however, historically has not wanted this predominantly black and Latinx neighborhood to be visible. The 1966 Redevelopment Program for the State Fair of Texas made this clear: “If the poor Negroes in their shacks cannot be seen, all the guilt feelings revealed above will disappear, or at least be removed from primary consideration.”

Today, it is not only seen; it is heard. On the street, music flows out of cars in vibrations that can surely be felt by tiny creatures on the ground. Blue jays and crows greet each morning in Joppa. People say hello to one another from front lawns and give nods to passing vehicles—I see you, you are not invisible. There is music in South Dallas of every kind. It’s simply symphonic.

Read more from the Observer:

- The Clothes That Make the Man: Jose Villalobos’ art redresses the macho traditions of norteño culture.

- More Highways, More Problems: Highway expansion is the Lone Star State’s status-quo solution to easing traffic—but it actually leads to more congestion and displaced communities.

- Republicans Come to Texas to Prepare for the 2021 Redistricting Battle: The right has an audacious plan to, once again, use the redistricting process to maintain power.