by Naveena Sadasivam

August 17, 2018

–

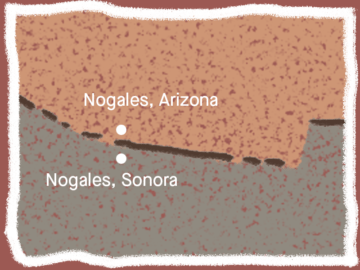

On July 27, 2014, monsoon rains hit the sister cities of Nogales, Arizona, in the US, and Nogales, Sonora, in Mexico. As the rain poured down, floodwaters rushed west of the Mariposa Port of Entry, clogging a 60-foot section of the border fence with debris. The bollard-style fence, with posts buried at least 7 feet underground, had been designed to let water pass through, but the intensity of the flooding and the size of the debris, which included tree trunks, toppled it.

For longtime Nogales residents on both sides of the border, the incident felt like déjà vu. Six years earlier, monsoon rains had flooded downtown Nogales, Sonora, a city of about 210,000, trapping merchants in their stores, causing $8 million worth of damage, and drowning two people. That time, too, the culprit was border infrastructure.

In the 1990s, US Border Patrol had built a series of steel walls between the two Nogales towns to deter illegal activity. But traffickers simply began using the drainage tunnels between the towns to get into the United States. The agency then installed grates in the tunnels, but traffickers cut through them. In the escalating arms race, Border Patrol finally constructed a 5-foot-high concrete wall in one of the tunnels. In 2008, monsoon floodwaters built up behind the wall, collapsing the tunnel on the Mexican side.

Until the 2008 floods, the International Boundary Water Commission (IBWC)—the binational agency that carries out the provisions of US-Mexico water treaties—had no idea that Border Patrol had plugged up a tunnel the commission had built to mitigate flooding. Border Patrol refused to take responsibility.

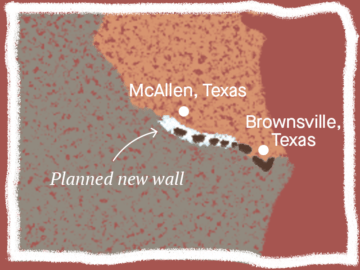

Over the years, border walls and fences have exacerbated flooding in both the US and Mexico. Environmental advocates and local activists in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas now fear their communities will also face increased risk of flooding as a result of new segments of border wall planned for the region. In March, Congress allocated $1.6 billion for border enforcement, including $641 million for border-wall construction in the Valley. Of the 33 miles of fencing and walls planned, the agency expects to build 25 miles of what are called levee walls—12-foot high concrete wall with 18-foot bollards on top—in Hidalgo County, as well as 8 miles of bollard walls in adjacent Starr County.

“The Rio Grande Valley isn’t really a valley, it’s a delta,” says Melinda Melo, an organizer for the No Border Wall Coalition. “There are flooding risks here in the same sort of way as in Nogales.”

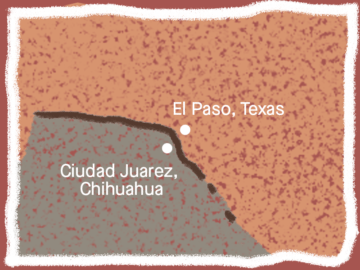

In 2006, the arid sister cities of El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, experienced the wettest monsoon period on record, receiving about three-fourths of their average annual precipitation in one week. The heavy, sustained rains resulted in flooding in both towns. The flooding in Juarez was particularly severe, with losses totaling $600 million (pdf). El Paso suffered $200 million in damages. Geographers believe the disparate impact was at least in part a result of debris clogging the Mexico side of the grates that Border Patrol had installed in tunnels.

In 2007, officials with the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Arizona (a US National Park) warned border authorities that a planned 5-mile segment of fence to be built along the park’s southern border would impede the movement of water in the flash flood-prone washes that traverse the international border. Construction was completed in 2008. Sure enough, that same year, debris stacked up behind the fence, acting like a dam and pushing water into nearby private businesses and the port of entry at Lukeville, Arizona. The US Department of Homeland Security, Border Patrol’s parent agency, promised to upgrade the fences to let water through; the design would prevent flooding, the agency said. But in 2011 floodwaters were so strong they knocked a segment of fence over again.

Environmental advocates expect that the 25 miles of levee walls planned for Hidalgo County will worsen flooding in Mexico. During floods, waters that rise up the side of the levee can dissipate on the other side, but advocates fear that water will be dammed by the concrete and metal structure planned for the top of the wall, causing flooding.

Additionally, if a July 2018 map of proposed border construction from Border Patrol is accurate and overlaps with a similar map from 2017, the 8 miles of bollard walls planned for Starr County intrude into a floodplain. In 2010, then-IBWC commissioner Edward Drusina told Border Patrol officials that modelling showed (pdf) construction of border walls in Starr County would result in “substantial increases in water surface elevations and deflections of flow.”

“There’ve been severe rains already in McAllen and Brownsville”—two towns in south Texas—“just in the last few months,” said Laiken Jordahl, a borderlands campaigner with the environmental group Center for Biological Diversity, in July. “Rains of that volume will almost certainly be backed up by this style of border wall.”

IBWC and Border Patrol have long been at odds over border infrastructure. Border Patrol’s priority has been to embrace anything believed to deter illegal crossings. Congress has frequently weaponized that mission. In 2005, Congress passed the REAL ID Act, which allowed the secretary of Homeland Security to waive dozens of laws that stood in the way of building a border wall. The Bush administration used that authority to clear the way for 654 miles of fencing across the US-Mexico border.

In 2010, when Border Patrol wanted to build about 14 miles of bollard fences in Roma, Rio Grande City, and Los Ebanos (all in Texas), the IBWC initially opposed the plans, citing the increased risk of flooding and loss of life, both in those cities and in their sister cities on the Mexican side. The US half of IBWC is bound by a 1970 treaty (pdf) that prohibits taking actions that would worsen the risk of flooding in Mexico. Border Patrol persisted in pressuring IBWC to issue what it called a “unilateral decision” to approve the border wall construction. The agency hired Baker Engineering, a global consulting firm that contracted with the federal government to build the border wall, to develop a new model that posited only 10% to 25% of floodwater would be blocked by the fencing and concluded the infrastructure wouldn’t result in severe flooding. The same firm a year before had concluded there would in fact be “noteworthy floodplain impacts from the fence.”

Eventually, the US side of the IBWC caved in to Border Patrol’s demands and, in 2012, the water agency gave the go-ahead for construction. Those sections were ultimately never built due to a lack of funds. The IBWC’s Mexican counterparts were not pleased with the US officials’ capitulation. They wrote (pdf) that the fence represented “a clear obstruction of the Rio Grande hydraulic area” and that it would “cause the deflection of [storm] flows towards the Mexican side.”

Now the Trump administration has revived the possibility of building the sections of border wall that were a point of contention between IBWC and Border Patrol in 2011. Landowners and activist group in the Valley have been served notices by Border Patrol in the last few months about the agency’s plans and some have received condemnation letters with offers of money for access to their property. In response to protest by a coalition of environmental and human rights groups, the agency extended the comment period by 30 days earlier this month. But the agency still hasn’t held a single public meeting about the wall in the Valley.

Meanwhile, Mexican officials with the IBWC are wary of the latest round of proposed construction, too. In April 2017, the chief engineer with the Mexican section of the IBWC, Antonio Rascón, told NPR that Mexico is “not in agreement with construction of a wall in the floodplain that affects the transborder flow of water.”

“We’ve seen lots of pressure by Homeland Security so that this project moves forward,” he said. “But the kind of wall they’re planning would have drastic effects on transborder water flows.”