Three Takeaways From Mexico’s Landmark Presidential Election

Leftist Andrés Manuel López Obrador is promising “profound changes” after his emphatic victory. What does that mean for international politics, immigration, NAFTA and Trump?

México has turned left. On Sunday Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), of the Morena party, became the first candidate in 90 years to win the Mexican presidency without the backing of one of country’s two traditional parties, the center-right National Action Party (PAN) or the populist Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

AMLO’s win turned out to be the largest of any Mexican president since elections became freer and fairer in the mid-1990s, after decades of authoritarian rule by the PRI, the party of President Enrique Peña Nieto, who will leave office in December. AMLO won every single state except for one, including all the conservative states of the North, which had rejected him in two previous presidential bids. His vote share was more than the PRI’s and PAN’s combined.

Mexico’s stunning political transformation in 3 very different maps pic.twitter.com/oY3f9ZU53A

— Tom Phillips (@tomphillipsin) July 3, 2018

Despite fears that indifference or Election Day violence would keep large numbers of voters at home Sunday, initial data indicates turnout was higher than the 2016 U.S. election at over 63 percent. After Peña Nieto’s disappointing six years of persistent violence, rampant corruption and sluggish and unequal growth, Mexicans wanted change and over 24 million of them, 53 percent of voters, decided AMLO was the candidate who could bring it about.

The first topic covered by AMLO’s victory speech was reconciliation. He spoke of “profound changes” that would be accomplished through dialogue and respect of the law. His priorities, he said, would be fighting government corruption and putting the poor first.

This is where the country stands after this landmark election:

1. Hope Won Over Fear

Throughout the campaign the PRI and the PAN appeared to be holding a contest over which party could persuade more voters of the terrible dangers ahead if they voted for AMLO: more deaths, more corruption and a failed economy. They were assisted in their efforts by the business elites that have thrived under past governments and their spokespeople in the media.

In 2006 and 2012, the PAN and the PRI, respectively, avoided electoral accountability for their actions in national government because they succeeded in convincing a majority of Mexicans that AMLO would turn the country into Venezuela. They tried the fear-mongering tactics again in 2018, but this time hope for something different prevailed.

While PRI and PAN relied on sophisticated media campaigns crafted by political consultants, AMLO tirelessly toured the country meeting in person with voters and explaining his vision of “true change”: fighting corruption in government, separating political from economic power and dealing with poverty and exclusion, the root causes of violence.

In a similar way to Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn’s supporters, AMLO’s urban voters used social media to fight back against the fear narrative and to share their enthusiasm.

2. Feminist to Become Mexico City’s First Elected Woman Mayor as Traditional Parties Implode

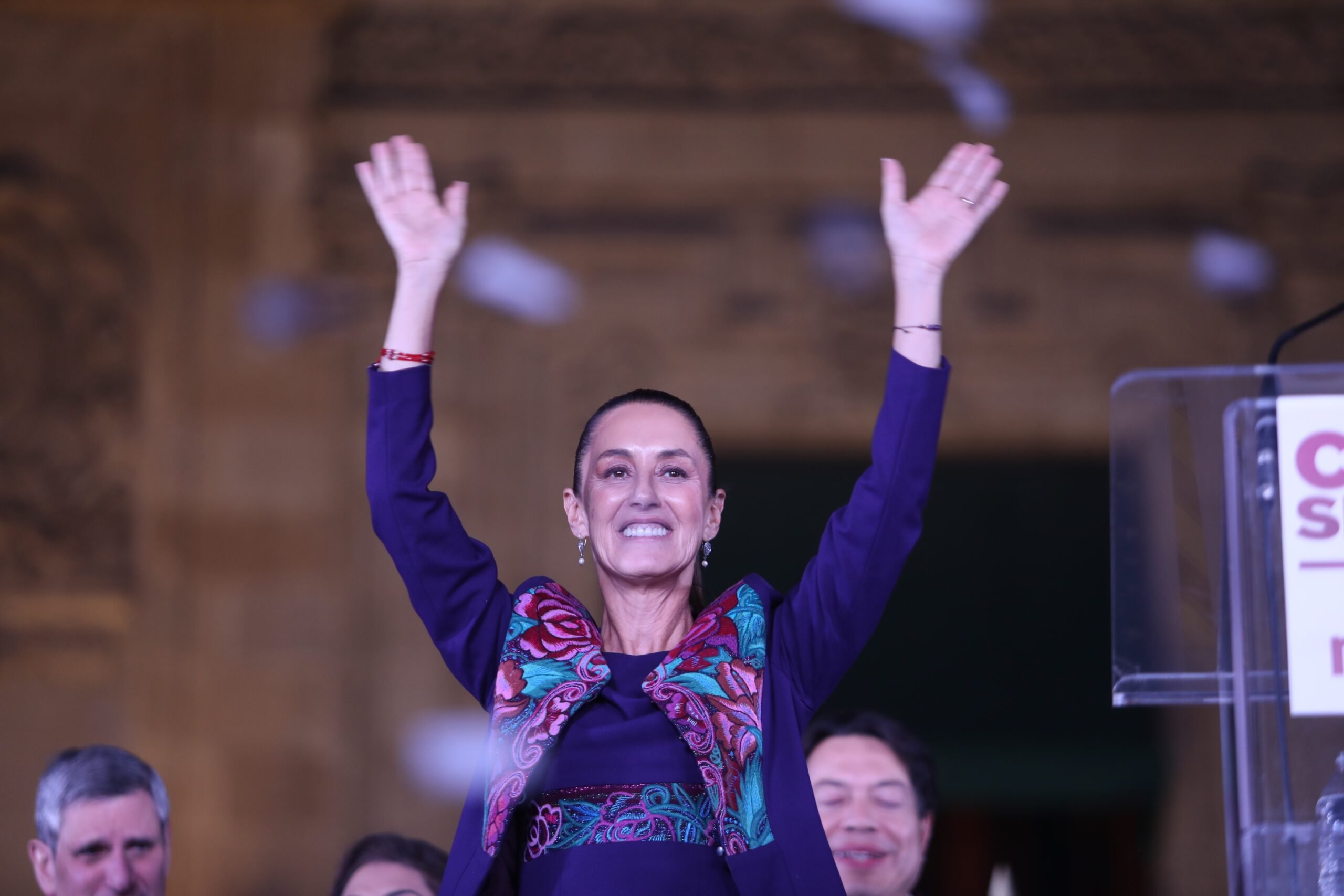

AMLO had strong election coattails, too. His coalition, Juntos Haremos Historia (Together We Will Make History) won a comfortable majority in both houses of Congress — 310 out of 500 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 69 seats out of 128 in the Senate — and more than half of the governorships at play. Claudia Sheinbaum will become the first woman elected to govern Mexico City, the second-most important elected office in the country and a position AMLO held from 2000 to 2005. Sheinbaum left the center-left PRD along with AMLO and was one of the founding members of the Morena party four years ago. An academic and proud feminist, she won with a margin of 16 points over PRD candidate Alejandra Barrales. This will be the first time the PRD loses the government of the capital since 1997.

While Morena emerged from the election as Mexico’s largest political party, the traditional parties collapsed. PRI saw its worst results in party history. Candidates up and down the ballot weren’t able to get over Peña Nieto’s dismal approval numbers and PRI corruption scandals. PRI won a little over 16 percent in the presidential race, did not win any governorships and its representation in the Chamber of Deputies will shrink from 204 to 44 seats, according to Oraculus.

PAN self-destructed. Its presidential candidate Ricardo Anaya insisted on building a broad left-right coalition with PRD. His robotic style failed to connect with voters, people were reminded of his eager support of Peña Nieto and he was accused of using political office for enriching himself. PAN will end up winning only the governorships of Guanajuato and Yucatán and, in the Chamber of Deputies, will go from 108 to 79 seats.

3. AMLO, Trump and NAFTA

Trump has been frequently blamed by U.S. commentators for the rise of AMLO due to his antagonism toward Mexico and Mexicans. This assessment could not be further from the truth. The three main candidates early on all positioned themselves against Trump. Understandably so because the U.S. president is incredibly unpopular in Mexico.

While Peña Nieto has canceled meetings with Trump in response to his verbal attacks, AMLO has said he is willing to meet with him to convince him of dropping his wall idea and anti-immigration policies. During the recent family separation crisis, AMLO pledged to respect the rights of Central Americans in Mexico and to defend the rights of all migrants abroad. He wants Trump to help fund development programs in the region so people will not be forced by poverty and insecurity to emigrate. Needless to say Trump will be unsympathetic and relations between the two countries will remain complicated. A meeting between AMLO and Trump is unlikely to happen before the November midterm elections, since Trump is currently relying on nativist rhetoric and policies to motivate his electoral base.

A progressive in his international outlook, AMLO favors peace and cooperation and constantly repeats that “the best foreign policy is a good internal policy.” Regardless, he understands how important to Mexico is the relation with the United States. He named a respected economist, Jesús Seade, to lead the renegotiation of NAFTA. AMLO agrees with Trump that salaries in Mexico should be higher but will oppose any changes that hurt Mexico’s rural economy. His team has said he is prepared to fight for NAFTA but is willing to give up on it if Trump persists on a zero-sum negotiation approach.

Mexicans have widely condemned Peña Nieto’s appeasement strategy with Trump. AMLO’s negotiating position will be stronger than Peña Nieto’s, not only due to his winning margin but because he is free to repair relations with Democrats in the U.S., which were badly damaged by Peña Nieto’s siding with Trump in 2016. He has named Marcelo Ebrard, the cosmopolitan former mayor of Mexico City, and Héctor Vasconcelos, a career diplomat, to handle foreign affairs in his transition team. Ebrard lived in California and has firsthand knowledge of U.S. politics. Those half-expecting a “clash of the populists” that would damage the bilateral relation beyond repair will be disappointed.