Three Things the Judge Says He’ll Consider in Ruling on Texas Fetal Burial Law

Of primary concern is whether the law would limit patients’ access to abortion or miscarriage care.

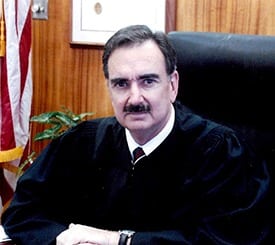

As the weeklong trial over Texas’ fetal burial law wrapped up on Friday, Federal District Judge David Ezra gave a good indication of what he’ll be focusing on in his decision.

The plaintiffs — a collection of Texas abortion clinics and other health providers — said the law requiring burial or cremation of fetal and embryonic tissue after abortions and miscarriages at medical facilities is offensive and unnecessary. They argued that Senate Bill 8 burdens patients’ right to freedom of speech and religion as well as their access to health care. (Typically, the tissue is treated like other medical waste, incinerated and placed in a sanitary landfill, though patients can choose to bury it instead.) Among those testifying against the law was Blake Norton, who was forced by a Catholic hospital in Austin to bury the remains of her miscarriage. The Observer published her story in April.

The state argued that the law demonstrates “profound respect for the life of the unborn.” In response to testimony that it would distress patients, state attorneys noted that the law doesn’t require patient consent; if women don’t want a burial, providers don’t have to tell them.

Ezra, who temporarily blocked the law from taking effect in January, said he’ll take closing arguments from both sides in writing by August 3. He hasn’t said when he plans to rule, but on Friday he gave an idea of what he’ll be considering:

1. Does the law constitute an undue burden on abortion access?

This question has been the primary focus for Ezra throughout the trial. Amy Hagstrom Miller, president of Whole Woman’s Health, a plaintiff in the case, testified that her organization struggles to find vendors willing to do anything from delivering water to resurfacing the parking lot because of anti-abortion hostility in Texas. Difficulty finding vendors to comply with the requirements of SB 8 would force providers to stop offering abortion services, said Hagstrom Miller, who called the law a “backdoor attempt” to shutter clinics. Currently, there’s just one vendor in Texas that will work with her clinics to dispose of medical waste.

Ezra didn’t seem convinced that the state had an adequate plan to ensure providers could meet the requirements of the law. Individual witnesses from funeral homes and cemeteries offering to help weren’t enough, he said. When the state submitted a list of the 1,300 funeral homes in Texas, Ezra noted that it shows the “potential for capacity,” but there was no evidence they’re actually willing to take tissue from abortion clinics.

Attorneys for the state pointed to a new registry under SB 8 of organizations willing to offer free or low-cost burial services as one solution to the potential capacity issue. But David Kostroun, a regulatory official with the state health department, said on Thursday that only 16 entities had signed up. Kostroun also acknowledged that the agency doesn’t verify applicant information, do background checks, ask about financial stability, ensure there is a legitimate business, require a contract or stipulate any minimum criteria.

The uncertainty is “a problem,” said Ezra, adding that he needs to see evidence of how many businesses contractually agree to dispose of remains, how many remains they can take and where they’re located. “Is there a failsafe, a backup, a way women can receive these services if something did not work?” he said in his closing statement.

2. What authority does the state have to pass this legislation?

Ezra wants to know why the state has the legal authority to pass this law under the stated purpose of “dignity” of the “unborn child.” He noted at the close of the trial that the state had taken off the table the typical argument that the law was intended to protect the health and safety of patients, and instead focused on the fetus — an “unusual” move that makes the case “extremely unique.”

Throughout the trial, Ezra seemed less receptive to the plaintiffs’ arguments that the law imposes the state’s arbitrary idea of what is “dignified” on patients and providers who have diverse religious and personal views. “I am not here as an ethicist,” Ezra said, noting his job was to determine whether the law infringes on the right to abortion. But he came back to the state’s “dignity” point on Friday, asking for an explanation of the state’s authority to pass the law on these grounds, and why it can be applied selectively to certain remains (the law includes exceptions for tissue that comes from pathology labs or from miscarriages or abortions that occur at home).

3. The challenged law includes miscarriages, not just elective abortions.

The framing of this case as a question of undue burden on abortion access is insufficient, in part because the law encompasses tissue from miscarriages, too — something Ezra acknowledged at length in his closing remarks.

That experience made Norton feel “shamed and stigmatized,” she said in testimony against the law on Monday. If she had known about the hospital’s burial policy, she said, she would have sought care elsewhere.

The shuttering of abortion clinics due to these new requirements is “what some people want,” Ezra said, alluding to conservatives in the Republican-controlled Legislature. But it’s important to remember that the legislation could also limit care for patients who miscarry, even patients who may support the law, he added. “The question of whether women would be able to get services is of great concern, and should be to every citizen in Texas.”