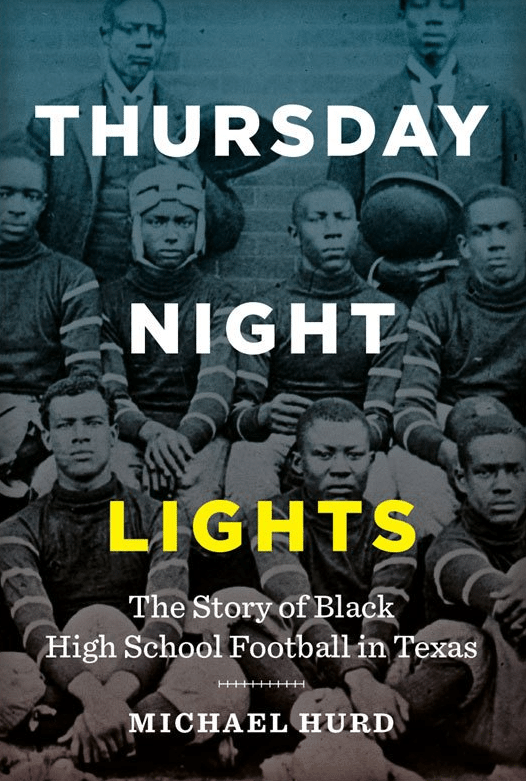

‘Thursday Night Lights’ Pays Tribute to Black Football History in Texas

Michael Hurd's new book shows how the stories we tell ourselves about Texas football history are woefully incomplete.

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

$26.00; 304 pages

“I was puzzled the first time I heard the phrase ‘Friday Night Lights,’” writes Michael Hurd in his new book, Thursday Night Lights: The Story of Black High School Football in Texas. Hurd grew up in Houston in the 1960s and attended segregated schools. Like most black schools, his had to play its games on Wednesday and Thursday nights. Those were the games Hurd attended and remembers. White teams used the stadiums on Fridays. As a former football player says in the book, “‘Friday Night Lights? That’s white folks.’”

After a long career in sports journalism, Hurd is now the director of Prairie View A&M University’s Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture. He has also written a previous history of black football players and coaches: Black College Football, 1892-1992: One Hundred Years of History, Education, and Pride. It is no accident, then, that he landed on this topic. “Emotionally, I have been writing this book since adolescence,” Hurd writes in the introduction.

In Thursday Night Lights, he tells the stories of the players, coaches and teams that competed on those Wednesday and Thursday nights. Until the end of the 1960s, black high school students in Texas who wanted to participate in academic or athletic competition were not welcome in the University Interscholastic League (UIL). So men from the Colored Teachers State Association of Texas created the the Texas Interscholastic League of Colored Schools in 1920 in order to give students of color the same opportunities their white counterparts got from the UIL. The organization was renamed to the better-known Prairie View Interscholastic League (PVIL) in 1963. “This book,” Hurd writes, “is meant to both remember and introduce the PVIL: what it was, why and how it came to be, why and how it came to an end.”

Sadly, in a state where football is king, the history of the PVIL has all but been forgotten except within black communities.

The 260-page book is divided into six chapters that cover the creation of the league and some of its best players who went on to the collegiate and professional levels; the coaches who created great, even legendary, football programs; and what happened during integration, when the UIL absorbed the PVIL. There are also two geographically specific chapters: one focused on players who came out of the so-called Golden Triangle in southeast Texas, and one about Houston, specifically the annual Wheatley-Yates Thanksgiving Day football game, which was “the largest high school sports event in the United States” from 1947 to 1966. The chapters are divided by a section in the middle of the book with photographs of some of Hurd’s subjects.

Hurd writes candidly about racism and racial violence throughout the book. The triumphs of black players, their coaches and their communities are contextualized within the harsh confines of legal, cultural and systemic discrimination and hate. One of the most memorable and tragic stories is that of quarterback Eldridge Dickey, who played high school ball in Houston. Dickey’s resume was “as brilliant as any, and more so than most,” Hurd writes. In college, Dickey “racked up 6,523 yards passing and 67 touchdowns” and “led his team to an undefeated black-college national championship season.” He was the first pick of the Oakland Raiders in the 1968 draft. “After the preseason,” though, “Dickey never played quarterback again,” instead forced to be a wide receiver and kick returner. Hurd says this was normal for black quarterbacks, that everyone knew “it was a dead-end gig with no future beyond high school or college”; no professional team wanted “a black player as a team leader and the face of a franchise.” Hurd writes that Dickey died at the age of 54 “from a stroke, exacerbated by a broken heart from a pro career that never was.”

Sadly, in a state where football is king, the history of the PVIL has all but been forgotten except within black communities. The result is that there are evidentiary issues that Hurd acknowledges early on. “The league’s official documentation doesn’t go much deeper than yearly results of state championship games,” he writes. “This lack of data left me at the mercy of aging memories and myths.” No statistics, only stories.

Since Hurd is working from a nearly blank slate, it often feels like there is too much in this book and yet also not enough. He wants each story to be fleshed out enough to have meaning within the larger narrative of black football in Texas, but then he moves on quickly to the next one. The result is a dense book full of long paragraphs, lots of names and an amazing amount of detail.

Though this book is long overdue, it is also right on time. We are currently having a collective cultural discussion about whose history gets told, how we choose whose stories matter, and which historical characters get cast, quite literally, in stone or metal to be celebrated for years to come. Hurd shows that the stories we tell ourselves about the history of football in Texas are woefully incomplete. The PVIL was not simply something that happened and so should be acknowledged. It was, in fact, the showcase of the best football talent in the state during its tenure. When the UIL absorbed the PVIL in the late 1960s, Hurd writes, “the UIL received a sudden infusion of … blue-chip black players who would legitimize the league’s claim of having the best high school football talent in the land.” That’s the kind of crucial history we’ve forgotten, and Thursday Night Lights offers an important corrective.

Michael Hurd will read from Thursday Night Lights on Oct. 21 at 6 p.m. at Book People in Austin.