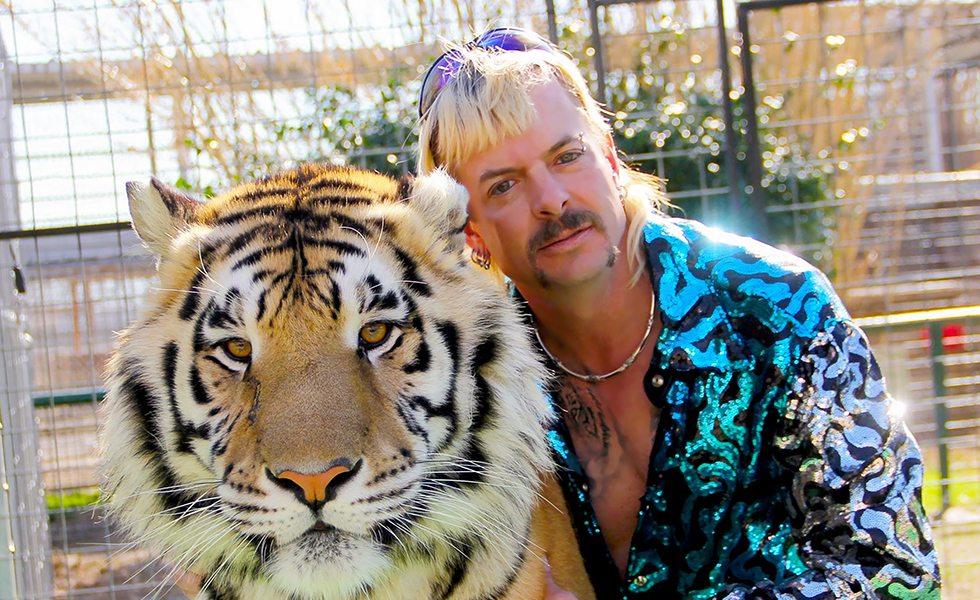

Tiger King Could’ve Told a Tough Story of the Legal Mistreatment of Animals, But It Didn’t

Netflix’s runaway hit is a salacious interpersonal drama that buried what could have been a hard-hitting exposé of the patchwork regulations that are failing to protect animal welfare and public safety.

Just three weeks ago, during a narcotics raid in Hidalgo County, authorities discovered a white Bengal tiger, a bobcat, emus, porcupines, and a kinkajou being held illegally. Most of the animals were taken to the Austin Zoo for medical evaluation and rehabilitation, but there are still privately owned exotic animals all over Texas going largely unprotected. This is the latest incident with exotic animals in the state—something similar happens about once a year—ranging from large predators being spotted wandering in heavily populated areas to children getting mauled and killed. Due to an ineffective patchwork of regulations and a barely developed system for tracking such animals, animal welfare advocates have been fighting for harsher laws on the private possession of exotics for years. But in Texas, it’s been to no avail.

While these animals were being rescued from a private residence, millions across the country were bingeing Netflix’s Tiger King: Murder, Madness and Mayhem. With the release of this new docuseries right at the outset of the COVID-19 crisis, we stumbled upon a streaming service free-for-all. The show’s success has undoubtedly been helped by the unusual conditions tethering hordes of people to their couches—34.3 million people watched the show in its first 10 days—but it’s also a spellbinding tale in its own right, with thrills and twists and salacious surprises. Eccentric Oklahoma zoo owner and tiger breeder Joe Exotic, a self-described “gay, gun-toting cowboy with a mullet,” and a polygamist to boot, puts on quite a show. And it’s hard to look away.

The problem with Tiger King is that, for a show purportedly about animal abuse, maybe it should be a little harder to watch. While the story calls attention to the mistreatment of exotic animals in the U.S., it privileges the titillating interpersonal drama as the main story. Yes, the absurdity of this issue is laid bare, as we watch with shock and awe as tigers are crowded into makeshift cages in roadside zoos. It’s reasonable to wonder: How is this allowed? But even as the creators set out to call attention to this policy, they fail, as Tiger King puts animals through the same exploitative portrayals it accuses its subjects of perpetrating: It gets swept up in the glitz and glam, the glory (and gore) of this animal-obsessed kingdom, and forgets about the animals themselves.

In a move that surprised many animal welfare advocates, the show demonizes the only person in sight who seems to be genuinely fighting for reform. Believe what you will about Carole Baskin’s past (despite allegations, there has still been no evidence to link her to the disappearance of her first husband, Don Lewis), but activists and scientists have spoken out against the suggestion that she mistreats animals at her sanctuary. Big Cat Rescue is accredited by the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries, the highest level of accreditation a sanctuary can receive, and Baskin has a sterling reputation in the animal welfare community.

Trafficking in this sort of false equivalence between two strong personalities—in this case, one an openly greedy, disloyal, unhinged opportunist and the other a lifelong animal welfare champion who has been viciously harassed and targeted for murder—is a sensationalizing trope. At the end of the day, we are meant to see the war between Joe Exotic and Carole Baskin as a neutralizing story of revenge and retaliation between two egoists where no one really knows what they’re fighting about, just that they’ve been fighting for a very long time. But this is not the case—we do know what they’re fighting about. The feud isn’t just a battle of wills untethered to any real values or issues; it’s a battle between a man who believes he deserves the right to do absolutely anything he wants and a woman who resolved to stop him.

A production built around an organizing principle of justice would not paint these two figures as equals. It allows the cause itself to fall away completely. Still, director Eric Goode, New York entrepreneur and founder of the Turtle Conservancy, seems to distrust Baskin just as much as he does Exotic. Goode told The New York Times that “I felt that we had a responsibility to look into, to some degree, her missing husband.” But murder conspiracy theories aside, his critiques of her animal welfare record seem arbitrary. Sure, Goode wanted to portray Baskin as yet another self-serving big cat lover, dressing in leopard print every day and showcasing exotic animals for attention and glory. But Big Cat Rescue in Florida is a real nonprofit, unlike the “zoos” of Joe Exotic, Jeff Lowe, and Doc Antle, which are shams, seedy labor-abusing operations, or quasi-cults disguised as businesses.

If Tiger King didn’t demonize Baskin enough, it’s striking that the direct threats of violence against her are treated almost as a joke. The show exposes the rampant misogyny in the big cat world, from Antle’s coercive cult-like group of female employees, to Lowe’s multiple sexist comments. Meanwhile, the real terror of Baskin’s brush with death is glazed over. It’s a typical pattern in cases of violence against women: Perpetrators will state aloud their intention to act violently toward a woman, and it’s never taken seriously until an attack happens. Exotic had publicly threatened to kill Baskin dozens of times, called her a bitch online countless more, and shot a doll resembling her in the head for fun. Yet the seriousness of this all but fades away, only adding to the reality-TV drama.

A blurring of the lines between just laws and unjust laws that surely existed for Joe Exotic could have made for a gripping study of legality and criminality in Tiger King. The nature of this kind of documentary, “the big cat version of Blackfish,” is meant to be about failures of justice that are still technically legal. A series deeply investigating the gray areas, with a focus on which laws need to change right now, could have had a profound impact. As it stands, the show leaves so many themes unexplored and questions unanswered. What have we learned about the laws on exotic animals throughout these episodes? Very little. The series is notably remarkable for how much access its creators had to their subjects, but they never effectively brought it back to the real cause.

“If you think we don’t have our own Joe Exotics in Texas, you’re wrong.”

Still, for Katie Jarl Coyle, the southwest regional director of the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), the widespread discussion of Tiger King gives her hope. Currently, Texas is the only state in the country that allows exotic animals to be regulated county by county, relying on local clerk’s offices and sheriffs to enforce the few laws that do exist. Because there’s no state agency overseeing how many exotic animals are in the state at any given time, the animals aren’t tracked and no one knows for sure where they’re kept. The result is a dangerous mishmash that has made the state a safe haven for exotic animal owners and an ideal region for smuggling animals across the border.

For the past four legislative sessions, the HSUS and animal welfare allies have fought for a law restricting private possession of exotic animals in Texas. Their bill has died each time. In 2019, the bill passed in the Senate but died in committee in the House when the session ended. Now Coyle believes we’re in the midst of a perfect storm to finally talk about this issue. “Private ownership isn’t just about animal cruelty, though that is certainly a major issue. It is also about public safety and public health,” she told the Observer. “Wild animals can carry deadly diseases, as we are acutely aware of right now.”

Due to the strong private lobby, the HSUS and bill sponsors have already had to roll back the original goal of altogether banning the private possession of exotic animals. In last year’s proposed bill, the main tenets of the policy were still intact: ending the buying and breeding of exotic animals. But it would still have allowed for circuses, fairs, and films to keep using exotic animals and grandfathered in Texas’ many current exotic pet owners. Even so, it’ll be an uphill battle to pass any new law in Texas. Despite the fact that there’s been bipartisan support for stronger regulation, longtime advocate Robert “Skip” Trimble says Texas is a state where “they don’t like to have any laws that they don’t have to have.”

Coyle put it bluntly: “If you think we don’t have our own Joe Exotics in Texas, you’re wrong.”

Find all of our coronavirus coverage here.

Read more from the Observer:

-

State Employees Criticize Texas’ Uneven Approach to Worker Safety Amid COVID-19: A slow, patchwork response to COVID-19 has jeopardized worker safety for some of Texas’ lowest-paid public employees.

-

COVID-19 Cases Now Tied to Meat Plants in Rural Texas Counties Wracked with Coronavirus: The outbreaks, which are being investigated by the state health agency, represent the first reported cases of the virus inside Texas meatpacking plants, and are in rural areas where medical resources are already stretched thin.

-

Spinning Their Wheels: Dallas’ paltry public transit system makes owning a car all but required. So as the metroplex booms, many low-income residents are shut out of jobs and services they need.