‘Tower’ Animates America’s First Mass School Shooting

For a film about a mass shooting set in a state still hotly debating newly loosened gun restrictions, the documentary Tower takes a decidedly apolitical approach to the role firearms play in public life.

The film, which premiered during SXSW, chronicles the events of the 1966 University of Texas tower shooting that left 14 dead, including an unborn child, and 32 injured. The first half of Tower follows the shooting in near-real time, interweaving the stories of six or so survivors who are portrayed by actors. The film’s main characters include the sniper’s first victim, then-18-year-old Claire Wilson, and the officers who shot the sniper, Austin cops Ramiro “Ray” Martinez and Houston McCoy.

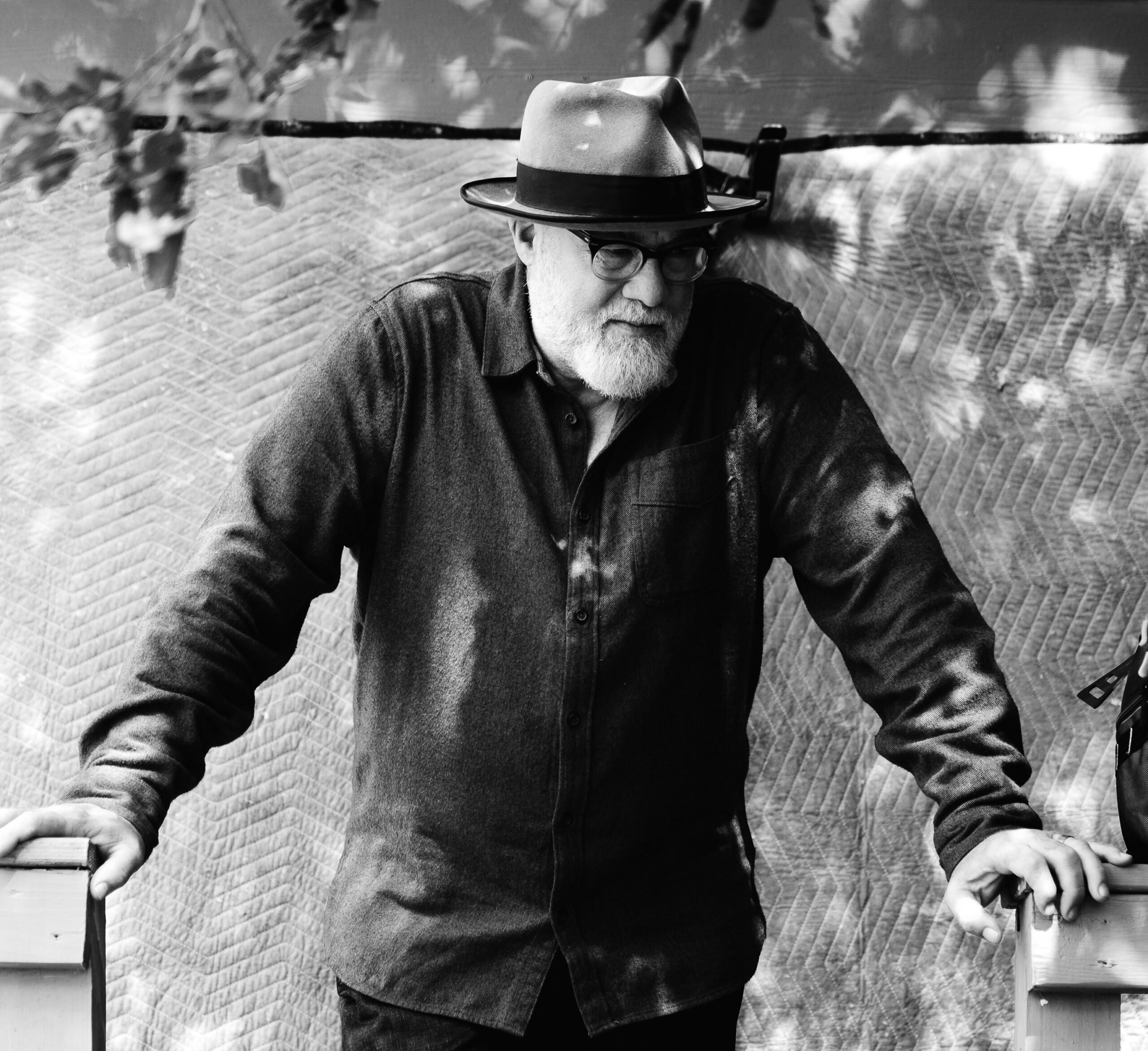

To combine survivors’ memories with limited archival footage of the shooting, director Keith Maitland employs rotoscoping, an animation technique that traces outlines of live-filmed footage (as seen in Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly). Young actors play the survivors in the rotoscoped scenes, their script a composite of taped interviews and details culled from “96 Minutes,” the Texas Monthly article Maitland optioned for Tower. The result is a film in both black and white and color, with hints of psychedelia, showing Austin as it was in the 1960s.

The university will dedicate a memorial to the tower victims on August 1, 2016, the shooting’s 50th anniversary and the day Texas’ campus carry law is set to go into effect.

A student witness describes the scene on campus as a “frozen snapshot,” with victims seemingly stuck in place, unable or unwilling to flee. Instead they stay put, peering around corners to see what might happen next. This contrast deepens when Maitland juxtaposes the Tower footage with film of more recent school shootings, like the 1999 killings at Columbine High School when panicked students fled the library.

Tower is well-timed for the current debate on gun control, yet Maitland leaves the politicizing to his subjects. Wilson, for example, testified at the Texas Capitol against campus carry legislation in 2013 and 2014, while Ray Martinez is shown in the film as a guest speaker training law enforcement on combating active shooters.

Other than oblique references to Charles Whitman made during news reports and interviews on the day of the massacre, Maitland presents the shooter mainly as a specter. Tower includes no photos of Whitman, nor information about his background or suicide note. The decision to focus solely on the victims makes Tower a survivors’ history, not unlike another SXSW 2016 film about mass gun violence, Newtown.

At Tower’s close, Maitland notes that the university will dedicate a memorial to the victims on August 1, 2016, the shooting’s 50th anniversary and the day Texas’ campus carry law is set to go into effect. Maitland said he was “glad” of the coincidence.

“It gives us an opportunity to have this conversation without having to manufacture a connection,” he said, after Tower’s final SXSW screening. “The connection is there.”

Maitland, who introduced each of the festival’s three full-house screenings with tears in his eyes, took home both the SXSW Grand Jury and audience awards for documentary feature as well as the Louis Black “Lone Star” award, named for the festival co-founder who served as an advisor on the documentary.

Tower will air during PBS’s Independent Lens 2016-2017 season, and Maitland said he hopes for a nationwide theatrical release on August 1.

[Featured image: Reporter Neal Spelce, played by Monty Muir, rotoscoped into a scene from the 1966 University of Texas shooting in Tower, courtesy of the film.]

Correction, March 22: The original article mischaracterized Martinez’s work with a law enforcement training class on combating active shooters. Martinez, who is retired, was a guest speaker to the law enforcement training class. He did not own the business conducting the training. The Observer regrets the error.