‘Trinity’ Offers a Beautifully Fragmented Portrait of the Inventor of the Nuclear Bomb

Hall paints a portrait of Oppenheimer through refraction, resulting in a novel that captures his life fully, but indirectly.

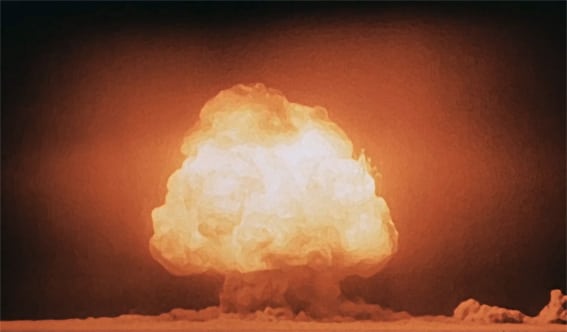

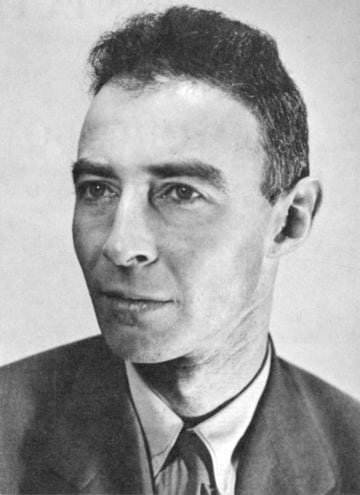

It’s been more than 73 years since the first nuclear bomb the world had ever seen exploded in the New Mexico desert. That bomb was the product of the Los Alamos National Laboratory under the direction of J. Robert Oppenheimer, and the code name for the project — inspired, Oppenheimer would later hint, by a John Donne poem — was “Trinity.”

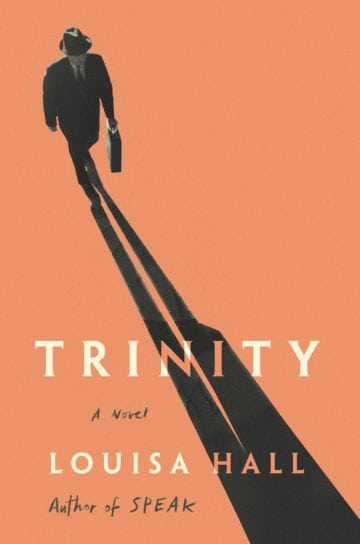

Trinity, the third book from novelist Louisa Hall, takes an oblique look at Oppenheimer, the man who would spend the last years of his life variously trying to explain away and atone for his involvement in creating the weapon that would claim tens of thousands of lives in Japan. It’s a startling novel that asks how well we can ever really know anyone else, no matter how much we scrutinize them.

HarperCollins

$26.99; 336 pages

Hall, who has taught creative writing at the University of Texas and the Austin State Hospital, has chosen a fascinating structure for Trinity: It’s told in seven discrete narratives — “testimonials,” Hall calls them — from fictional characters who crossed paths with Oppenheimer at some point in their lives.

Among them is Sam Casal, an Army spy tasked with trailing Oppenheimer in 1943, when the scientist was teaching at Berkeley, not long after he’d been asked to participate in the Manhattan Project. Rumors that Oppenheimer was a Communist had been swirling; Casal catches him in a tryst with a leftist physician named Jean Tatlock. (Not all of the characters in Trinity are real, but Tatlock actually was a friend and lover of Oppenheimer.)

Casal is having problems of his own — his long hours trailing Oppenheimer have left him paranoid, and he’s starting to suspect that his wife is harboring a secret about her past. His assignment investigating the scientist has left him in a permanently confused state: “That’s what it seemed like at the time: that because I couldn’t understand Opp, I couldn’t trust myself to understand anyone or anything else.”

In each of the seven narratives, the reader learns more about the narrator than about Oppenheimer. It’s a risky gambit that pays off beautifully — Hall paints a portrait of Oppenheimer through refraction, resulting in a novel that captures his life fully, but indirectly.

Her technique proves particularly effective in the section narrated by Grace Goodman, a member of the Women’s Army Corps assigned to work at Los Alamos. Goodman has been having an affair with a married scientist who works with Oppenheimer, “the mayor of our little Shangri-la on the mesa.” Her contact with Oppenheimer is limited, but she provides a startling account of the Trinity test, which she witnesses: “I grabbed for somebody’s arm, and I saw that the women around me had turned into X-rays, and that my own arm was an X-ray as well, our bodies having become in an instant nothing more than revelations of the bone cages we’d lived our whole lives in.” (Some witnesses of atomic explosions reported a light so bright they could see their bones, though it’s unclear whether the phenomenon is real.)

In each of the seven narratives, the reader learns more about the narrator than about Oppenheimer.

Perhaps the most moving testimonial comes from Sally Connelly, a young woman who takes a job as Oppenheimer’s secretary at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey,, in 1954. Connelly is struggling with self-hatred; she’s self-conscious about her weight and can’t stop comparing herself to her sister, who was obsessed with photographs of the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and who died of heart failure caused by an eating disorder.

Oppenheimer confides in Connelly as he prepares to be interrogated by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, which suspected him of being a Communist sympathizer. Connelly realizes Oppenheimer is spinning his life story, perhaps trying to dodge responsibility for the violence that resulted from his work at Los Alamos: “We tell our lives to other people like stories. We make characters out of ourselves. If we’re skilled, we make ourselves seem almost lifelike.”

Trinity ends with a chapter by a journalist assigned to write a profile of Oppenheimer in 1966, a year before his death from throat cancer. Her observations of the scientist are quietly devastating: “Watching him now, I realized how small and how weak he really was. … In the end he, too, had lived caught up in the same incomprehensible tumult, caught in the same uncertainty I’d always hated, and why he’d done what he had done to take control of that chaos didn’t matter as much anymore. I was sorry for him for what he’d suffered, as a result of the suffering he caused other people.”

Hall regards Oppenheimer with a kind of pity. She never tries to mitigate the damage he caused the world, but she also refuses to paint him as an inhuman monster, despite his bloody legacy. Trinity is a dizzying, kaleidoscopic marvel of a book, and a beautiful reflection on the impossibility of creating a truly accurate narrative of any person’s life. As Sally Connelly reflects, Oppenheimer wanted to rewrite his own story, “[n]ot realizing there are always holes in the story, that the holes are the most powerful part, that it’s the holes people fall into, disappearing forever, dragging everyone and everything they love with them.”