How Do Technical College Grads Fare in the Job Market? It’s Complicated.

If you’ve spent any time watching daytime TV, you know the pitch: Industries are critically short on skilled workers, and with the right training, an exciting career with great pay could be waiting for you! Enroll now!

Among technical colleges, the competition for students is fierce, and many make big promises to lure recruits (and the federal loan money they often bring). Texas has been cracking down on for-profit chains, even revoking the license of Dallas-based ATI Career Training Centers. As former Texas Workforce Commission Chairman Tom Pauken explained in 2011, “Schools that misreport employment information about their programs potentially exploit vulnerable individuals with false hopes.”

Today, the commission ensures that for-profit trade schools are up-front with recruits about placement rates—and specifically whether graduates are working in a field related to what they studied. For trade schools, more than any other sort of higher education, it’s a critical measure of success. To stay open, such colleges need to keep their program-related employment rates above 60 percent.

But those regulations don’t extend to public trade schools. Each year, almost 30,000 students attend one of 11 campuses in the state-funded Texas State Technical College System (TSTC). To compete against for-profits and their enormous ad budgets, public trade schools have relied mostly on good public relations; local papers near TSTC campuses often run glowing stories about high placement rates and soaring industry demand.

In 2012, the Marshall News-Messenger cited “a job placement rate at nearly 90 percent” for TSTC’s Marshall campus. In a Valley Morning Star story this March, the chair of TSTC’s surgical technology program flatly declares that “all graduates are placed in jobs.” TSTC makes similar claims online about its Waco campus: “on average, industry has more job openings than TSTC has graduates. TSTC boasts placement rates of more than 90 percent.”

George Reamy remembers how impressed he was the first time he heard numbers like those, back when he taught English at TSTC Waco. “I remember talking to people about that,” he said, “and they kind of whispered to me, ‘hey man, that’s not quite what’s goin’ on.’”

In fact, the “success” rate for graduates includes students employed in any field or enrolled in further education. Say you’ve got a job at Taco Bell, graduate from a biomedical technology program, and then keep on working at Taco Bell. TSTC counts that a “success.” “You’ll never see phrases like ‘program-related’ or ‘in their field of study’ or even ‘technical’ next to the word ‘job,’” Reamy says.

TSTC campuses in Marshall and Sweetwater recently begin posting data on training-related employment. At the West Texas campus in Sweetwater, which advertised a 90 percent placement rate for 2013, the degree-related job placement was just 65 percent. In the News-Messenger last December, TSTC Marshall Director of Career Services Benji Cantu announced a “substantial” placement rate of 81 percent—but didn’t mention the school’s program-related placement rate for 2013 was a less-substantial 40 percent.

Generally, Reamy says, the future for tech school grads is more complicated than these statistics let on. He points to a 2012 survey in which TSTC Waco graduates say they wish the school had been more up-front about their job prospects; the mixed reviews include some very positive comments, and more than a few from graduates who discovered their education was of little help in the job real world. Four call their degrees “a waste.”

For the same reason Texas doesn’t let for-profits make inflated claims about their programs, Reamy says, public schools ought to be transparent with recruits. “People make life-changing decisions based on stories like these,” he says. At his blog, “Watching Texas Technical Colleges,” he keeps up a drumbeat of criticisms against TSTC’s placement claims.

TSTC System Vice Chancellor Eliska Smith is familiar with these sorts of charges. But the truth, she says, is that there’s no systemic way to know which jobs are truly training-related. Unemployment insurance data doesn’t track graduates who leave Texas is prone to broad generalities that could accidentally list a graduate as working outside their field of training.

As an example Smith points to an automotive technology graduate who gets work as a mechanic at a Wal-Mart auto shop. State employment data wouldn’t count that Wal-Mart job as field-related. If a nursing graduate hires on at a school district and not a hospital, the state’s best data would consider that an unrelated field.

“There’s some fallacies in using ‘in-field,'” Smith says. “What matters to us, and what we think matters to our students is that our students are getting jobs.”

For the same reasons, even the Texas Workforce Commission—which has been requiring for-profits to maintain a 60 percent field-related employment rate—is moving away from its current measure, according to Richard Froeschle, the commission’s director of labor market and career information. Froeschle, one of the state’s experts on measuring career school outcomes, says the workforce commission relies today on self-reported numbers from schools, but is working on an objective measure more like what TSTC uses. “A level playing field, if you will,” Froeschle says.

Michael Bettersworth, an associate vice chancellor and data guru at TSTC, is well acquainted with the limitations of the data on training-related employment. For now, at least—until there’s better data on graduates’ jobs—he says it’s the wrong way to measure a school’s success. “I have gone down the rabbit hole of these data elements and philosophical debates,” Bettersworth says. “There are major structural limitations on the available data that limit the assumptions you can make.”

For now at least, Bettersworth says the best measures of TSTC’s success are how many graduates find jobs and how much its graduates earn after leaving. He says it’s a natural fit for TSTC, where the institutional mission is to grow Texas’ economy through workforce training.

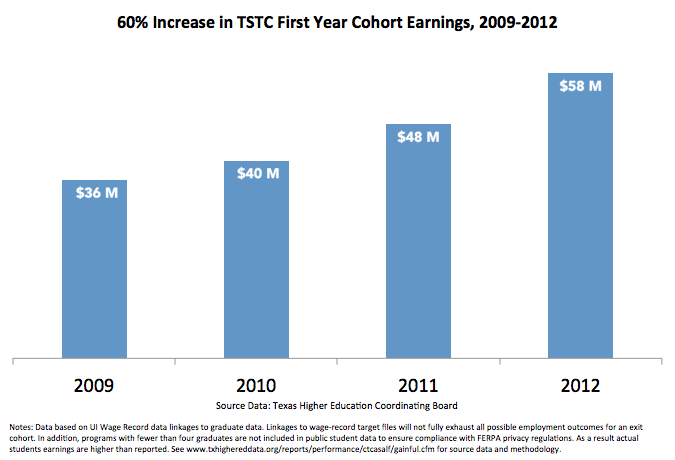

Pressure to keep those numbers up has only increased now that the Legislature has tied TSTC’s state funding to its graduates’ earnings. The state’s calculations don’t include whether that job relates to what a graduate studied—they rely instead on a measure of graduates’ wages—a figure Bettersworth happily notes has risen in the first years of the new funding scheme (see the chart to the right).

For its willingness to stake its funding on graduates’ performance, TSTC has become a darling of the results-based higher ed movement that both Gov. Rick Perry and gubernatorial hopeful Greg Abbott have embraced. In his campaign, Abbott’s plan for higher ed includes funding all sorts of institutions—not just trade schools, but community colleges and four-year universities as well—based on some measure of their performance.

The trade schools offer a good example of how complicated school performance metrics can get, even for a relatively straight-forward question like whether graduates got jobs related to their studies. Performance metrics for, say, a university philosophy department wouldn’t be so straightforward.

And while folks like Froeschle and Bettersworth are fine-tuning measures for the state—probing data sets for weaknesses and being careful not to assume too much—what prospective students see in their local newspapers more often are local trade school officials’ certain claims that “all graduates are placed in jobs.”

Reamy says that’s where his frustration still lies: in the local recruitment pitches, where the nuance is often stripped from the numbers. “If there’s no good data on where people end up after graduation, officials need to quit talking about their employment rate without explanation or caveat,” Reamy says. “Anything less leads to false expectations and disappointment on the part of students and their families. … It boils down to integrity.”