The sun was sinking toward the horizon when brothers Alejandro and Juan Simental drove their pickup less than 10 minutes from a Motel 6 to their job site: a pricey new toll road they were helping to build alongside busy State Highway 288. A week before, they had left their home in Arlington to work in the flat southern edge of Houston’s suburbs, the bustling intersection of State Highway 288 (SH 288) and Beltway 8. That’s where their employer, Choctaw Erectors, a steel construction company, was subcontracted to help build the Texas Department of Transportation’s latest privately operated tollway.

They shared their no-frills motel room with a coworker, sleeping only a few hours just to get up and work again. Their shifts were punishing—nine to 12 hours, often overnight, seven days a week. But that evening, as the Houston sky gradually dimmed to a streetlight-stained dark gray, Alejandro, Juan, and five others on their crew established a rhythm. Alternating thumps and whirrs sounded as they laid and bolted corrugated metal decking, piece by piece, onto the tollway’s four bridge girders, 85 feet above the ground.

As the sun began to rise on June 21, 2019, Alejandro, 21, who stood around 5 feet 3 inches tall and was stocky like his brother, was working on a section of the bridge just a few feet away from Juan. There were about 15 minutes left in their shift when Juan reached the end of the first girder. Realizing that the 6-foot double safety lanyard he wore, which was tied to a safety line, did not allow him to reach the second girder more than 7 feet away, Juan briefly unhooked the lanyard from his safety harness and walked across the steel decking.

Foreman Jorge Carlos was the only one to hear the scream as Juan tripped and fell 85 feet, head first. Seconds later, realizing his brother had fallen, Alejandro let the metal sheet he was holding drop from his hands and clatter to the ground. He rushed to an elevated boom lift that lowered him to his brother’s side.

Blood was already soaking into the soil. To the west of Juan’s feet lay his white hard hat and his right brown slip-on boot. His black plastic headlamp was still glowing. Co-workers gave Juan CPR. Police arrived in four minutes, the medic nine minutes later. That was too late. At 4:58 a.m., just two minutes before their shift was to end, Juan was pronounced dead. He was 22.

Choctaw foreman Jorge Carlos was later questioned about how project managers made sure all employees were properly tied to safety lines since the project had no safety nets. His reply: “It’s their responsibility. I can’t babysit everyone.”

Texas has 698,839 miles of road lanes, the distance of 28 laps around the earth—more miles of roadway than any other state. Highways are a source of state pride. The slogan “Don’t Mess with Texas” originated in 1985 from the Texas Department of Transportation’s (TxDOT) campaign to keep roads clean of litter. But the state also leads the country in the number of deaths among workers who build its highways, a fact that TxDOT officials don’t openly discuss. TxDOT’s failure to address and hold contractors accountable for accidents on its highways may be part of why Texas’ highway worker fatality numbers are so high.

From the bottom of the contracting chain to the administrative offices of TxDOT, no one took responsibility for Juan’s death, according to public records and court documents reviewed by the Texas Observer. Alejandro says he never saw anyone on site either from TxDOT or from the Spain-based general contractors, Dragados USA, Pulice Construction, and Shikun & Binui America, collectively known as Almeda Genoa Constructors. He had assumed Choctaw, a subcontractor, was in charge. At the time of the accident, no safety managers from Choctaw or from Almeda Genoa were on site.

In response to the Observer’s request for comments on the accident, Choctaw owner Kevin Ball deferred to Almeda Genoa, which did not comment.

Juan’s death raises concerns about who, if anyone, is held responsible when highway workers die in Texas, especially in public-private partnership projects where virtually all control of public infrastructure is handed over to a for-profit entity. In the case of Juan’s death, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) gave Choctaw a slap on the wrist with only a $5,000 penalty, even after finding the company violated federal safety standards by failing to provide proper protective equipment. Kevin Ball, the owner of the Decatur, Texas-based steel erection company, admitted to OSHA investigators that he made workers provide their own safety harnesses and lanyards or took money from their paychecks if they used the company’s protective equipment.

TxDOT, by using these public-private partnerships, is a way for them to shuffle off responsibility. And sadly, OSHA rarely shows up unless there is a death or serious injury.

But other players in the massive construction project were assessed no penalties at all, not by OSHA and not by the state agency, even as the number of worker accidents on the 10-mile-long toll road continued to pile up.

The Observer found that the agency had incomplete information on Juan’s death and failed to address accidents that the Observer uncovered. Even though the toll road was built on state-owned land with funds from federal tax revenues, TxDOT passed the buck on highway workers’ and drivers’ safety, indemnifying themselves against liability for any and all accidents based on its contract with the private equity firm that now controls the SH 288 toll road and its revenues for the next five decades.

TxDOT declined the Observer’s request for an interview with the agency’s occupational safety director or with the agency’s designated project director for the SH 288 tollway. When asked to explain specific actions TxDOT took after each serious accident, the agency commented, “TxDOT carefully examines every incident in a work zone.”

However, the agency did not find any records related to other workers’ accidents that resulted in hospitalization during the tollway construction, including one cited by OSHA. Its public information officers told the Observer that TxDOT “does not track injuries and fatalities of prime contractors or their subcontractors as a standard operating procedure” and only records contractor fatalities “if our office was made aware of the occurrence.”

In a list of roadway construction fatalities TxDOT sent to the Observer, the agency listed the contractor in charge when Juan died as “unknown.”

“TxDOT, by using these public-private partnerships, is a way for them to shuffle off responsibility. And sadly, OSHA rarely shows up unless there is a death or serious injury,” said Jeremy Hendricks, political director of the Southwest chapter of the Laborers’ International Union of North America. Hendricks added that compared to states like Illinois, in which 99 percent of roadway workers are represented by the union and represented in the transportation department’s workers committees, zero roadway workers in Texas are unionized.

OSHA never cited general contractors Almeda Genoa Constructors, even though company officials admitted to the investigators that they failed to ensure all workers on the site were properly trained and equipped before they started working. OSHA reasoned that the company’s direct employees were not responsible for the incident, even though the agency has a multi-employer citation policy that holds general contractors, along with subcontractors, responsible. In response to the wrongful death lawsuit later filed by Juan’s family, Almeda Genoa said: “The accident in question and damages were solely caused by third parties over whom this Defendant had no control nor right of control.”

In an interview, former OSHA chief of staff and policy advisor Debbie Berkowtiz told the Observer that OSHA “failed to hold those responsible accountable for this tragic death.” She noted that falls are a leading cause of death in construction, and employers are required by law to provide proper fall protection equipment. “The agency sent the wrong message.”

Statewide, TxDOT has erected traffic safety signs that flash playful messages such as “Gobble, Gobble, Easy on the Throttle” or “The Eyes of Texas Are Upon You” as part of its “End the Streak Campaign” to reduce traffic-related deaths. But the eyes of TxDOT seem to be overlooking roadway workers who continue to experience as many deaths as 10 years ago. Studies on the safety conditions for Texas roadway workers are nonexistent.

Apart from an email TxDOT issued about Juan’s death, records and statements the Observer received indicate the agency took no independent action after the fatality. In a public statement, TxDOT referred questions to the private developer. “TxDOT’s contracted developer is responsible for the design, build, finance, operation and maintenance of the Drive 288 Project.”

The avoidable death of Juan Simental raises bigger questions about whether TxDOT is doing anything to monitor private contractors when it comes to worker deaths and accidents during road construction projects—on toll roads or otherwise.

The privately operated SH 288 tollway shows there’s plenty of money to be made from Texas’ roads, but it’s often workers like Juan who pay the biggest price.

“It’s a race to the bottom when it comes to the state of Texas and the way they deal with contractors. They often don’t care how the work gets done. And who gets hurt in the process,” Hendricks said.

Since 2000, when Texas’ population started to boom and its growth started surpassing all other states, the previously semi-rural community of Pearland has transformed into an ever-expanding suburb for families looking for cheaper homes close to the SH 288 corridor that leads to the Texas Medical Center and downtown Houston. Along with the people came more congestion.

During public meetings from 2007 to 2013, community members called for an HOV lane or a public railway to be built on the median of SH 288 to alleviate congestion. Those alternatives, they argued, would encourage commuters to share rides and put fewer cars on the road.

What they got instead was a 10-mile, billion-dollar tollway built on state-owned land at a rate of $106 million per mile. The same citizens who called for HOV lanes or a train are now paying some of the state’s highest toll fees.

During a February 2007 public meeting to discuss alternatives for SH 288, resident and medical librarian Marilyn Goff told TxDOT, “Tolling will only benefit the rich and put money into the pockets of contractors and profit-seekers.” Now retired at 70, Goff told the Observer she can’t afford to pay for the tollway. But as Goff predicted, revenue from the SH 288 toll road has filled the pockets of profit-seekers.

Actividades de Construcción y Servicios, S.A. (ACS Group) is now the sole owner of the Blueridge Transportation Group that owns and operates the toll road, which runs from Beltway 8 to US 59 in downtown Houston, along SH 288. The company reported earning $74 million in revenue from the tollway last year. The fee for the road, as high as $30 for a round trip during rush hour, is already one of the state’s highest. But there is no limit to how much ACS Group can charge or how much it can raise tolls under its agreement with Texas.

Back in 2005, then-Governor Rick Perry proposed creating a 4,000-mile network of privately operated toll roads called the Trans-Texas Corridor, prompting opposition from environmentalists, property rights advocates, farmers, business owners, and taxpayers’ rights activists. Many Texans were angry that the roads would be owned and the tolls collected by foreign investment firms.

Transportation activist Terri Hall has been organizing Texans against tolled roads since the state lifted its ban on toll roads back in 2001 and then permitted private entities to control roadways in 2003. Prior to this, state roadways were funded exclusively by state and federal gas taxes. Unlike standard TxDOT projects, these private operations, called concession projects, cede control of a roadway’s entire process—the design, construction, operation, and maintenance—for a period of 52 years to private investment firms. It’s why private firms can charge drivers exorbitant toll prices, especially when traffic is at its worst.

“The government pimped out Texas to seek out foreign toll operators from France and Spain. They put out on the front lawn of the Texas Capitol a sign that read ‘Texas is for sale. Name your price,’” Hall said. Around this time, she created the group Texans for Toll-Free Highways and has been fighting since to eliminate toll roads in the state.

While TxDOT has argued that privately operated highways shift the financial burden from taxpayers to the private sector, Hall argues that taxpayers often end up stuck paying for construction costs and decades of tolls until the contracts end.

Hall explains that private investment firms controlling the roads milk money from the public in several ways. The firms often self-deal construction contracts to their own subsidiaries that answer to the private entities rather than going through TxDOT’s normal competitive bidding process. For instance, ACS Group doled out construction contracts to its wholly owned subsidiaries Dragados USA and Pulice Construction to work on the SH 288 tollway. Construction costs are often inflated with various change orders that TxDOT cannot control. Private firms have no cap on how much they can charge drivers for tolls. They use a congestion pricing model to charge drivers more when traffic is at its worst and can levy heavy fines and even criminal penalties for tolls paid late under their contracts with the state.

The government pimped out Texas to seek out foreign toll operators from France and Spain.

“They’re literally extracting the highest possible rate from the traveling public and exploiting congestion rather than solving congestion,” Hall said.

Hall organized Texans to push the state Legislature to issue moratoriums on concession projects, starting in 2007 when 21 private concession projects under Perry’s plan came to the table. State Senator Robert Nichols, who had previously served as a Texas transportation commissioner, started to embed more public protections into these public-private partnership contracts. He rid contracts of the noncompete clauses, which had essentially awarded a private entity a monopoly in any road building activity within an area, and applied stricter standards before projects could pass the Legislature.

“My main objection is that when you have a roadway owned by a governmental entity that’s collecting tolls, the decisions that are made are made in the best interest of the people. When you have a toll authority that’s owned and operated by a corporation whose primary motive is to make a profit and benefit the stockholders, then those decisions are made in the best interest of the stockholders,” Nichols said.

The Observer found that over the past five years, there have been at least 119 workers’ compensation accident claims filed against the four primary private road developers—including the ACS Group subsidiaries, Zachry Construction, Webber LLC, and JD Abrams LP—awarded concession contracts by TxDOT, according to data from the Texas Department of Insurance.

Due to widespread opposition, Perry’s Trans-Texas Corridor was essentially dead by 2017. Perry managed to grandfather in five concession projects, four of which were awarded to the Spanish company Ferrovial-Cintra: the LBJ-635 Express Corridor, the North Tarrant Express and another segment of North Tarrant Express/ I-35 West completed later (all three in the Dallas-Fort Worth area), and State Highway 130 in Central Texas. The last to be built was the State Highway 288 tollway.

Those concession projects typically received about one-third of their funding from federal loans and another third from tax-exempt private activity bonds. “These private firms get all this other money from the feds, from the state. They make enough money in those early years, even when it’s underutilized, so they cover at least their equity and usually a handsome profit before these things go belly up,” Hall said.

That’s exactly what happened to the private State Highway 130 toll road, 41 miles that run through Travis, Caldwell, and Guadalupe Counties. When the SH 130 Concession Company filed for bankruptcy in 2016, the company’s main player, Ferrovial-Cintra, left SH 130 with millions in debt, pavement defects, and flooding problems. Bankruptcy court filings revealed that the company knew the highway would go broke but managed to siphon $329 million to pay for construction costs to a company Ferrovial created.

Two days after SH 130 filed for bankruptcy, TxDOT signed a contract for the 288 tollway project with the foreign investment firms making up the Blueridge Transportation Group, now solely owned by the Spanish infrastructure firm ACS Group.

After Juan’s death, the accidents continued as the Blueridge Transportation Group assembled the SH 288 toll from 2016 to the end of 2020.

No one from the state nor from the toll road general contractor seemed to consistently force contractors to comply with workers’ safety laws under OSHA and the federal Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, which regulates traffic control for highway construction. There were dozens of other injuries during the tollway’s construction, including at least six workers hospitalized with debilitating injuries, OSHA records show.

According to OSHA investigation reports and court filings, workers commonly reported that there was no one monitoring safety conditions, no flagger or spotter, and no safety training.

On December 2, 2017, one worker under the direction of ACS subsidiary Pulice Construction hit an unmarked electrical line on the company’s Houston premises, causing power to surge through and shock him. No report was filed with OSHA.

On July 11, 2018, at the Interstate Highway 610 intersection of the tollway, a highway concrete form without adequate support braces collapsed on two workers, both of whom suffered fractures. OSHA cited Almeda Genoa for failing to train the workers and to provide adequate support structures for the job.

On August 28, 2019, solid concrete blocks crushed a worker and severed his toes while he was emptying out a truck bed under the direction of ACS’s Pulice Construction subsidiary McNeil Brothers.

On October 7, 2020, a little over a year after Juan’s death, another worker was injured when he fell from a wall without fall protection equipment at the tollway’s intersection with Beltway 8.

On February 28, 2020, a truck struck a worker and drove over his legs as he was spreading concrete near the intersection of Beltway 8 and SH 288. Court filings revealed there were no spotters in place. The worker survived the incident, regaining his ability to walk and work one year later. No report was filed with OSHA.

Another worker was not so lucky. A similar accident occurred one year later on another Pulice Construction project for TxDOT just 20 miles west of the SH 288 tollway. The company’s foreman, Isidro Matamoros, died when a tractor backed into him and knocked him over. There were no spotters, and the tractor driver later told the police he had heard and noticed the impact, but he still proceeded to roll backward over Matamoros, crushing his body.

In total, the SH 288 tollway construction resulted in dozens of worker accidents, at least 10 motor vehicle accidents, two of which resulted in deaths, a pavement collapse, four class action wage theft claims, and seven lawsuits involving breach of contract claims, the Observer found in an extensive search of federal, state, and county court records.

Juan’s death and other accidents on the SH 288 tollway illustrate a small part of the dangerous conditions faced by Texas roadway workers.

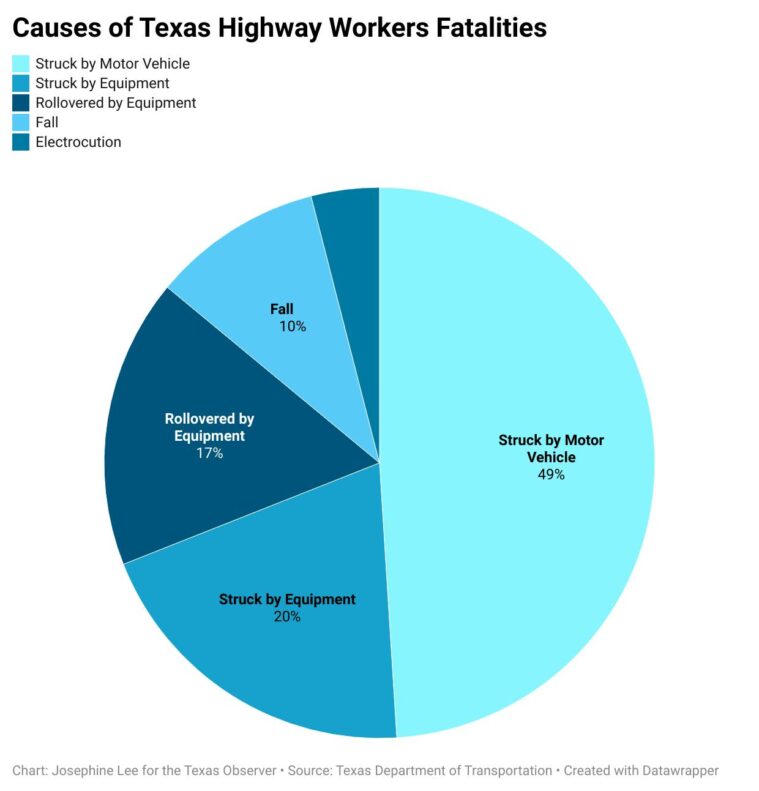

Texas has the highest rate of highway worker fatalities in the nation. Part of the reason is that

TxDOT’s general standards for ensuring workers’ safety are weak. In its two-page instruction for contractors titled “Standard Specifications for Construction” and its online Construction Manual, TxDOT largely defers to federal OSHA statutes and the state Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, which regulates work zone and traffic safety during highway construction, without specifying how TxDOT plans to enforce workers safety. In comparison, Caltrans, California’s state transportation agency, outlines specific requirements extending beyond its state or federal OSHA plans, and gives guidance on how to conduct each aspect of road construction safely in their Code of Safe Practices and their Construction Manual.

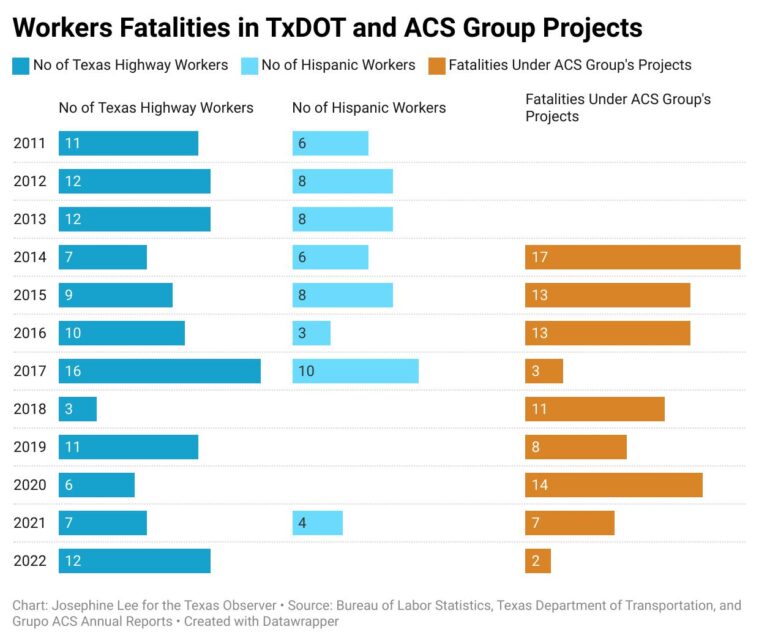

California, which has a larger population than Texas, has had at least 57 highway worker fatalities in the last 12 years, according to figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Since 2012, the state has reduced the number of fatalities from 10 to two in 2022. Illinois, whose transportation department frequently meets with a committee of unionized workers, has only had 28 highway worker fatalities in the last 10 years. In comparison, Texas has had 116 highway worker fatalities in the same period. In 2022, 12 roadway workers died, the same number as in 2012. Most of these workers were Hispanic immigrants.

Caltrans also establishes a safety plan for all projects, including state private-public partnership projects. In contrast, TxDOT has private contractors develop their own health and safety plan in accordance with general contract requirements.

Alemda Genoa did send TxDOT its safety plan, many provisions of which the company seems to have repeatedly violated, including requirements for safety training, as well as contractor identification and inspection of protective equipment. No course of enforcement from TxDOT was stipulated.

And TxDOT does not seem to have considered ACS Group’s own safety history. The company reported fatality numbers for its subsidiaries’ various projects, exceeding TxDOT’s own number in the years before the start of the tollway’s construction. TxDOT continues to award ACS subsidiaries roadway construction contracts even after two workers died and countless others were injured on its roadway projects.

Worldwide, from 2014 to 2022, 88 workers have died during projects conducted by ACS’ subsidiaries, an average of 11 deaths a year.

In the Chamartín district of Madrid, Spain, where the streets are lined with lush gardens, upscale restaurants, and boutiques, ACS Group’s headquarters tower over neighboring buildings. Swallowing one infrastructure company after another, ACS Group has been continuously ranked as the world’s largest public-private partnership transportation developer by Public Works Financing, an industry periodical. The company has more than 130 concession projects worldwide and investments worth over $60.5 billion. A publicly traded company, it took in a net profit of $727 million last year, a 66 percent increase from the previous year. Its largest market now, more than half of all its upcoming projects, is North America.

ACS alone continues to rake in millions from projects like the SH 288 tollway. And TxDOT is one of its biggest customers.

Here’s how that happened.

TxDOT initially awarded a 52-year contract to design, construct, maintain, and operate the private highway, to be built on a 10-mile median of a state-owned road that runs from Brazoria County to downtown Houston, to the private equity partnership called Blueridge Transportation Group. The partnership included the infrastructure investment groups ACS Group, the Israel-based firms Shikun & Binui and Clal Industries, London-based Infrastructure Fund, Canada-based Northleaf Capital, and an American company, Tikehau Star Infra.

Before construction began, ACS Group had only paid $80 million, or 8 percent of the total project costs. The company then doled out the $800 million construction contract to its own subsidiaries Dragados USA and Pulice Construction, which together with Shikun & Binui American formed the general contractors Almeda Genoa Contractors.

My brother’s life could’ve been saved if there was more security. There was no one looking.

Blueridge still owed two-thirds of the costs in loans at the time construction was completed in 2020: $357 million in federal loans, nearly $300 million in tax-exempt private equity bonds, and $17 million from TxDOT.

But by April of this year, ACS Group had bought out all other equity shareholders and is now the sole owner of the Blueridge Transportation Group.

And despite the slew of accidents on the SH 288 toll, TxDOT continues to award contracts to ACS Group and its subsidiaries, now totaling more than $4.7 billion for at least 22 projects. In just two years between 2019 and 2020, Texas roadway workers filed 20 workers’ compensation claims against ACS subsidiaries.

ACS’ Texas projects include the US 181 Harbor Bridge in Corpus Christi, yet another public-private partnership project that has displaced and made unlivable the surrounding low-income Black community of Hillcrest. The project is at least four years behind schedule after perpetual delays caused by safety issues and design defects.

No one, from the BTG spokesperson to the CEO of ACS Infrastructure to the president of their subsidiaries involved in the project, responded to the Observer’s multiple requests for comments via phone and email.

Alejandro and Juan Simental did everything together. Only a year separated Alejandro from Juan, the middle child of three siblings. Growing up in their hometown of Durango, Mexico, the brothers played endless hours of soccer, battled each other in video games, and planned their futures together. Durango is Mexico’s fourth-largest state but is sparsely populated. Fields producing corn, beans, and chilies and pastures filled with beef cattle make up most of the landscape. Compared to other Mexican states, fewer residents of Durango emigrate. But in 2016 when Alejandro turned 18, he and his brother went north to try their luck in the Texas construction industry.

They thought they’d found stable work with Choctaw Erectors in 2019. For six months, they built university and commercial buildings in North Texas, but never anything as tall as the 85-foot high SH 288-Beltway 8 tollway bridge.

“My brother’s life could’ve been saved if there was more security. There was no one looking. Us workers, we were all alone. Above, there was no one,” said Alejandro.

He never returned to the worksite after his brother’s fatal fall. Or to Choctaw Erectors. A few days later, Alejandro left for Durango to take his brother’s remains to his grieving family. When he returned to Texas a month later, he decided to work for himself. As an independent contractor, his income is not as stable. But he feels safer knowing he can better control his own working conditions.

It’s still difficult for Alejandro to speak about his brother. But he shared his story in the hope that other workers wouldn’t have to lose their lives before the government finally takes notice.

Today, motorists who pay to travel on the SH 288 tollway where the Simental brothers worked can see how the new toll road soars above commercial buildings, electrical poles, and evergreen trees, so high that cars seem surrounded by nothing but sky. Those who look down at the site from a plane can see how eight crisscrossing highway segments form what looks like a knotted cross.