The African American Quilt Circle of San Antonio is preserving personal, political, and historical narratives through the ancestral practice of quiltmaking.

“There’s a determination not to tell the true history, because no one wants to admit to the evilness of the people we celebrate as heroes,” said Deborah Moore Harris, the president of the quilt circle. The group’s latest body of work is currently on view at the Carver Community Cultural Center Gallery through December 16.

Moore Harris is an artist, retired Army veteran and one of the quilt circle’s four founding members. She works part-time at a craft store. About 20 years ago, she decided to make her first quilt after watching an episode of The Carol Duvall Show, an arts and crafts program that ran on HGTV from 1994 through the early 2000s. The quilt was a gift for her mother and stitched together the genealogical details of her ancestral tree.

“It is definitely not straight, but it is colorful and tells the story of my family.”

The quilt circle is celebrating its fifth season together. The group is made up of 30 members with varying skill levels who range in age from 19 to 90. They meet every second Saturday of the month at the Carver Public Library to exchange wisdom, techniques, and stories.

Nina Fennell is one of the Quilt Circle’s elders. When she passed away recently, her family donated the fibers she left behind to the group. They began sorting through the materials and quickly discovered quilt blocks that she started, but never completed.

Two of the quilts in the exhibition are quilts Fennell began that her quilt circle family finished in her honor. The group arranged fabric from her home into a traditional wagon wheel pattern, building on the foundation Fennel laid.

In quiltmaking, there is often no single person a quilt can be attributed to. Many hands sew single stitches to create a shared piece of art and history. The “Black Angel” quilt, also on view at the Carver, is another outcome of a collaborative endeavor. Almost all of the group’s members had a hand in the project and say each block was cut, sewn, embroidered and binded with intention and lots of love.”

When the quilt circle meets in the new year, they will pick up where they left off, working collectively to complete a single hand-sewn quilt.

Moore Harris says the group’s members are practicing the art of “taking a story and expanding on it.”

Dr. Lillian Jones joined the quilt circle four years ago and has two quilts in the exhibition.

“Lillian is the historian of our group,” Moore Harris told the Texas Observer.

Jones’ “Tex Mex Underground Railroad” quilt has taken on a life of its own since the exhibition began. “You definitely have much better quilters in the group than me,” Jones demured. “But I do love the history and the stories.”

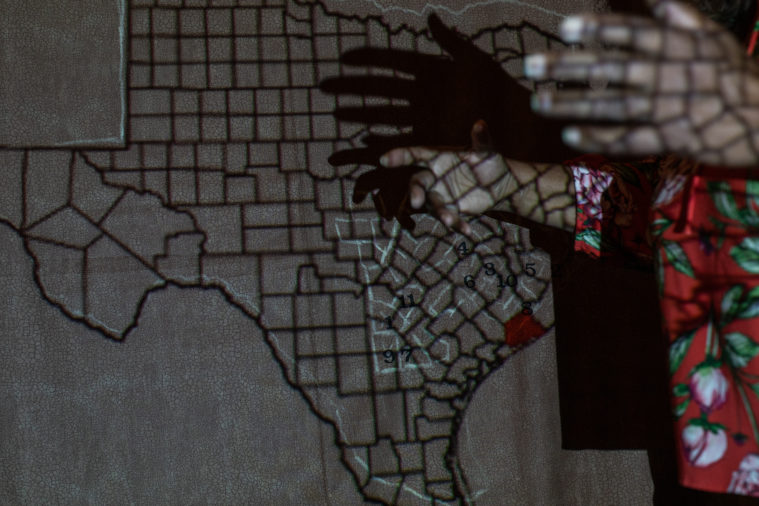

She used cotton fiber, dimensional paints, pipe cleaners, embroidery, appliqué, and traditional quilting techniques to sew a Black liberation history often omitted from textbooks. In 1821, Vicente Ramón Guerrero Saldaña became the second president of Mexico and abolished slavery in most of the country. Guerrero was a man of African, Indigenous, and European descent. Jones’s quilt illustrates the route traveled through Texas by an estimated 3,000-10,000 formerly enslaved people seeking liberation by crossing the Mexican border.

This unfolding of events provoked so-called Texas’ secession from Mexico in 1836, the Mexican-American War in 1848, and became an underlying cause of the so-called U.S. Civil War in 1865.

“These are not the things that are taught in school,” Moore Harris said. “You know how it is—people don’t give you the whole story.”

Since the exhibition began, the group has been contacted by multiple museums and historical organizations seeking to commission quilts that tell other stories conveniently omitted from the canon of history.

“I never would have dreamed that people would be so interested in this quilt,” Jones said with a laugh.

“Meanwhile, I’m just trying to get the thing done and not have too many threads showing.”

Two and a half years ago, Dr. Lillian Jones retired. She had spent 37 years working as an OB-GYN physician in San Antonio. At first, it didn’t feel like retirement. Between the start of the pandemic and the responsibility of serving as caregiver to her mother, the transition was not easy. Recently, she is finding more time to pour into her research and craft.

The 70-year-old fiber artist works out of her home in Converse where she lives with her sister, creates multimedia artwork, and tends to her garden. It is currently teeming with greens ready for harvest, just in time for the holidays.

“These are not the things that are taught in school. You know how it is—people don’t give you the whole story.”

Jones is a lifelong student. Through medical school, residency, and nearly four decades caring for babies and birthing patients, she has always carved out time for her creative practice.

“I would drag my friends to macrame classes, ceramics classes, you name it.”

She took her first sewing class in middle school, but picked the skill up at home from her mother Carolyn, an English teacher and expert seamstress who made her daughter’s wedding and bridesmaid dresses. “When I was in college, I’d send her a pattern with the fabric and she’d send it back done.”

Later in life, she learned to quilt through Northside Independent School District’s community education programming.

“Don’t be worried about the mistakes,” one classmate advised. “If the threads don’t match and the seams aren’t even, it’s still going to keep you warm.”

Those words of encouragement, coupled with Jones’ tenacious curiosity, led her to complete her first few quilts—the second one made entirely of corduroy.

When she brought her materials into class the day she began her corduroy quilt, her instructor looked back and said, “Oh my, corduroy.”

“What’s wrong with corduroy?” Jones wondered. “That will make it even warmer.”

The woman beside her lifted her gaze from the project before her and peered over at Lillian. “You don’t sew, do you honey?”

The fabric was impossibly thick and left a trail of fuzz that took days to vacuum out of the carpet. Nevertheless, she completed the quilt.

Jones has been sewing off and on for about 15 years. In that time, she has made 15 quilts.

“At the start of the year, I usually have an idea of what I’d like to do project-wise and gather up fabrics.” When the Observer spoke with Jones, she had just returned from a fabric hunting expedition at the International Quilt Convention in Houston.

She likes to get the idea for the design in her head before she thinks about the fabric. Usually, the idea comes from a picture.

“But every now and then, it’s from a story.”

Jones became curious about this particular story nearly 30 years ago.

She was on a cruise that stopped at multiple ports in Mexico. In one town, Jones wandered into a museum where an exhibit on Afro-Mexican culture took her by surprise. What struck her even more was a painting that included a familiar face. A museum label identified the young girl in the painting as Audrey Adams, half confirming what Jones suspected.

“I thought, ‘you’ve got to be kidding me!’”

Audrey Adams was a San Antonio public school teacher and no stranger to the Jones family when Lillian was a child. Adams taught Lillian’s mother and uncle and was still teaching by the time her older sister reached grade school.

“I was curious when I got back from the cruise and went to my mother.”

Lillian’s mother confirmed what she suspected—Adams was from Mexico.

“I knew she was a Spanish teacher but I never thought there were any Black people in Mexico.”

An assumption is often made that Black and Mexican are mutually exclusive identities that cannot coexist. This misconception is due in large part to revisionist histories that have been retold for generations.

Afro-Mexicans are descendants of formerly enslaved Africans brought to Turtle Island between the 16th and 18th centuries. The erasure of Afro-descendant peoples and their experiences has been institutionalized throughout Mexico’s history. After achieving independence from so-called New Spain in 1821, Mexico was a fragmented state. To cultivate a national sense of identity, government officials proclaimed that race and ethnicity did not exist.

During the Mexican Cultural Revolution of the early 20th century, Afro-descendant peoples and other ethnic groups were omitted from historical and cultural narratives. Artists, intellectuals, and government officials constructed an idea of Mexican identity around mestizaje, an ahistorical belief that the country’s racial and ethnic makeup consisted exclusively of European and Indigenous ancestry. The only legally recognized ethnic groups were white Spaniards, Indigenous peoples, and mestizos, a term used to describe a person of both European and Indigenous descent.

While conducting research for her quilt, Jones considered the flip side of the coin. “I was so impressed to learn that Mexico stopped doing race classification,” after abolishing slavery in 1821. “At the time, to me, that was so progressive.”

It is easy to understand how a lack of recordkeeping would serve those seeking freedom from colonial violence in. The advantages become even more clear when you consider how, historically, U.S. Census data has been weaponized to abet white supremacy. Nevertheless, census data is used by federal governments to distribute funds for social services to states and municipalities. The exclusion of Afro-descendant people from Mexico’s constitution and census is a form of structural racism.

In 2020, this injustice was partially rectified when Afro-descendant peoples were counted in Mexico’s national census for the first time. The victory was the result of yearslong organizing by grassroots advocacy groups, including Guerrero-based México Negro. While inclusion in the census is a step in the right direction, it has not immediately remedied inequitable social, economic, and political conditions in these communities. Years of marginalization and attempted erasure cannot be undone overnight. Today, the largest Afro-descendant communities are concentrated in the states of Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Veracruz.

Jones told the Observer that she began thinking about “Tex Mex Underground Railroad” four years ago, when she joined the quilt circle, thanks to a suggestion by the circle’s president at the time. She was intrigued, but the unpredictability of life kept getting in the way. “I had been thinking about the quilt forever and then I saw this film.”

A community film screening at the Little Carver Theatre set the project in motion. Produced by the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, “Just a Ferry Ride to Freedom” tells a pre-Civil War story of the Texas-Mexico border with an emphasis on the stretch between Laredo and Brownsville. The documentary highlights a network of interracial couples who sought refuge in Hidalgo County and offered ferry rides to “runaway” enslaved people seeking freedom across the Rio Grande.

Freedom is a relative term. After escaping to Mexico, some formerly enslaved people were lured into the trap of “lifelong servitude” by Spanish plantation owners. The violence inflicted in these settings often mirrored the horrors of chattel slavery. Every self-liberated person also faced the ongoing threat of recapture by bounty hunters.

The Texas Rangers, often mythologized, formed in 1836. As the state’s original police force, they carried out a campaign of “ethnic cleansing” that resulted in mass genocide and removal of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands in West Texas. Texas Rangers were also bounty hunters tasked with patrolling the state to hunt “runaway” enslaved people. But against the odds, attempts to form self-liberated maroon settlements south of the Rio Grande were successful in several cases.

Jones spent about a month reading articles and academic papers on the subject. She bought books related to the Underground Railroad, but did not find them to be of much use due to their exclusive focus on the Northern route.

She considered putting her embroidery machine to the task for the text on the quilt, but quickly realized there was too much information to capture. “At a certain point, all those stitches become hard to read.”

Instead, she opted for printed out pieces she could appliqué. Her primary sources are cited on the back of the quilt. She includes a historical timeline and other notes on the front.

Once she felt satisfied by her research, she began piecing together fibers, facts, and figures, thinking strategically about colors, symbols, and political context.

“I got an old map of Texas online, then used a projector to enlarge it,” she said. She traced the map onto the fabric and appliquéd her cut-out pieces.

The patterned fabric that depicts Mexico was the first selection she made. She allowed this piece to guide the color story for the rest of the quilt, pulling out the orange for Oklahoma, blue for Arkansas, and green for Louisiana. Similar to a state bird or flower, each state in the so-called United States has an official quilt block pattern. She incorporated the Oklahoma twister, Arkansas pinwheel, and Louisiana crossroads.

Jones naturally gravitates toward black and white fabrics and, as a result, has a strong selection available within her library of craft materials at home. The triangle pattern used to illustrate a majority of the state of Texas is repeated to create the quilt’s border and was pulled from her personal collection. The Nueces Strip hugs the natural border of the Rio Grande River and holds great significance in this story. Jones used a different black and white fabric she found at Mesquite Bean Fabrics on Austin Highway to demarcate this area from the rest of the state.

“That region was so crucial,” Jones said.

Between an unforgiving climate and sparse vegetation, an inestimable number of freedom seekers died at this point in the journey. “There was almost no water, temperatures over 100 degrees, poisonous snakes and spiders and nowhere to hide from bounty hunters.”

In a world where written record has intentionally omitted and misrepresented history, artful storytelling can be an act of narrative reclamation.

“When people come to see our quilts, they are surprised to learn about history,” Moore Harris said. “But that’s the whole premise of the [quilt circle]—to tell the story.”

“These Ain’t Yo Big Mama’s Quilts” will be on exhibition at the Carver Community Cultural Center Gallery, Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. until December 16, 2022. Entry is free and open to the public.