As more homicide cases go unsolved, the backlog of unsolved murders grows and serial killers are free to kill again. Too few police departments are effectively deploying their resources to stop them.

By Lise Olsen

February 8, 2021

From the January/February 2021 issue.

Nearly every week M.J. Jennings went shopping at the Dallas Galleria with her mother, Leah Corken, an 83-year-old widow who had moved to Texas to live near her daughter. On their last visit, Corken, who had tiny feet and hands, needed a new pair of slides, so they stopped at her favorite shoe store, the only one with a decent selection in size 5. Later, they caught a matinee at an upscale theater. “We always got a pepperoni pizza and split it,” Jennings said of their weekly ritual. “She always got her own popcorn from the popcorn stand and put on just the kind of butter she wanted.” They leaned back in reclining seats, munched popcorn, sipped wine, and laughed out loud at a comedy that featured Meryl Streep singing hilariously off-key. That afternoon, the only sad note came when Corken expressed distress over the unexpected deaths of two friends at Tradition-Prestonwood Senior Living, the luxury complex where she’d moved in 2010.

The next day, August 19, 2016, Jennings found her mother’s body facedown on the floor of her fourth-floor apartment. Her mother’s diamond-studded 18-karat gold wedding band was gone. Jennings called the police, but the patrolmen who arrived seemed uninterested in the missing ring or the passing of another elderly resident at the upscale complex.

Two months later, Dallas detectives investigated the theft of the 18-karat gold wedding ring of Norma French, who had also died at Tradition-Prestonwood. But the Dallas Police Department closed the case without identifying the culprit or recognizing a pattern in the robberies and deaths. French’s daughter, Ellen French House, asked her siblings to take pictures of their mother’s body. She couldn’t stop staring at the photos of her mother, lying facedown on the scarlet carpet in a pool of blood. To her, her mother’s ring finger looked red and swollen, as if someone had “pried the ring off of her finger,” she recalled. “There were a lot of red flags.”

By 2017, a total of nine residents had been found dead and apparently robbed at the same complex. Five lived on the same floor as Corken. But grieving relatives were repeatedly told that elders often die unexpectedly and misplace their valuables, according to accounts of the victims’ adult children.

Finally, in March 2018, a man named Billy Chemirmir, who had worked in home health care in the area since at least 2013, was arrested in nearby Collin County on suspicion of the attempted robbery of a 91-year-old. He was found in possession of a stolen jewelry box with paperwork that led police to the body of Lu Thi Harris, 81, found dead inside her Dallas home. With Chemirmir in custody, investigators executed a search warrant and discovered more valuable items that belonged to dead women. They also learned he had trespassed at a senior center and used a fake ID to pass a background check. For the first time, police began to make inquiries into the deaths of residents at Tradition-Prestonwood and other retirement complexes and private homes.

Chemirmir has since been charged with 18 homicides, including those of Corken, French, and Harris, and he’s been described by police as one of the most prolific serial killers in Texas. Prior to his arrest, local authorities had dismissed nearly all of those incidents as an unusual spike in natural deaths—a run of bad luck. But public records and interviews reveal that, time after time, investigators in Dallas made critical mistakes and overlooked or ignored signs of foul play.

For each cold homicide case there is a murderer at large who can keep killing. “How can you not address that?”

In nearly every case associated with Chemirmir, Dallas police failed to follow standard death and homicide investigation procedures published by the U.S. Department of Justice and other organizations. Both national and international guidelines recommend that forensic tests are appropriate when there are indications of criminal activity at a death scene, like the theft of jewelry or other signs of foul play. Several victims were missing items family members claimed were worth as much as $28,000, well over amounts that constitute felony theft in Texas. Some victims were found lying in suspiciously straight lines, as if they’d been posed or held down. The homes of others contained trails of blood. But officials assigned to review those cases initially considered them natural deaths and failed to take photos or videos of bodies, as investigation guidelines recommend, or to collect samples to test for blood or fingerprints potentially left by an intruder. The Dallas County Medical Examiner also did not immediately order autopsies on most victims whose deaths were later tied to Chemirmir.

“If the Dallas PD had put the dots together and sent out flyers, my mother wouldn’t be dead,” Ellen French House said. By the time she heard from a Dallas homicide detective in 2018, French House had been mourning her mother for two years. The cases connected to Chemirmir had gone cold. Victims’ bodies had been cremated or buried, and their apartments cleared. And all those previously undetected homicides had become part of a larger national problem: a backlog of more than 250,000 unsolved murder cases, a number that increases by about 6,000, nationwide each year.

This enormous backlog represents what the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) called a “cold case crisis” in a June report. As more and more homicide cases go unsolved, the backlog grows, allowing an estimated 2,000 serial killers nationwide to remain free to kill again. Too few police departments are effectively deploying their resources to stop them.

The backlog of cold murder cases keeps growing nationwide because police departments, including in Dallas, are solving a lower percentage of homicide cases than ever before, according to statistics from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). In prior decades, police in urban centers often solved as much as 70 percent of murder cases, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports. But by the 2000s, many metro departments regularly solved, or “cleared,” 60 percent or less of cases. Clearance rates refer to the numbers of cases cleared by arrests, deaths of suspects, or other means compared with the total number of murders reported in the same calendar year. Homicide clearance rates have continued to fall in the 2010s.

In 2019, four Texas cities—Houston, Arlington, Killeen, and Lubbock—cleared 40 percent or less of reported homicides, according to the latest FBI statistics. These dismal results have provoked an audit in Houston and anger from victims’ relatives, some of whom say detectives never contacted them.

Police in Dallas reported a clearance rate of just 54 percent in 2019. After 40 homicides were reported in May of that year, the highest monthly body count since the 1990s, local advocates requested more detectives and increased oversight. Instead, Governor Greg Abbott dispatched Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) troopers, who conducted 12,500 traffic stops in seven weeks—an effort that advocates viewed as unnecessary harassment rather than real help.

The Dallas Police Department, which has 3,000 officers and a $500 million annual budget, initially assigned only one homicide detective in 2018 to reexamine dozens of deaths that might be linked to Chemirmir. The detective was initially assigned exclusively to the investigation, but later juggled other murder cases. In 2018, the department’s 16 to 19 homicide detectives handled an average of more than 10 new murder cases each. That’s more than twice the recommended caseload, even without extra time for working older homicide cases. Police chiefs are constantly balancing the need for officers on the street with the need for detectives to investigate surges in murders, but murders are being shortchanged, advocates say.

Nationwide, few police departments permanently dedicate any investigators to cold murder cases. In 2016, only about 7 percent of the nation’s 18,000 law enforcement agencies had cold case squads, according to the NIJ. “Cold cases constitute a crisis situation,” said Tom McAndrew, a Pennsylvania-based detective who argued for more resources as part of a NIJ cold case working group from 2015 to 2019. For each cold homicide case, there is a murderer at large who can keep killing. “How can you not address that?” he said.

Dallas should have kept its detective on the Chemirmir case full time and much longer, given the number of potential victims involved, said James Adcock, the president of Mid-South Cold Case Initiative, a nonprofit that provides assistance on cold cases, and a member of the NIJ working group.

Adcock argues that police reformers should insist that departments refocus on murders—and demand answers about the growing backlog of unsolved homicides. Improving results doesn’t necessarily require an increase in a police budget, but rather a shifting of funding to investigative manpower, training, and forensic tests. Larger departments can boost clearance rates by prioritizing murder investigations and exploring innovative solutions, such as publishing data online on unsolved cases to seek tips, hiring civilians to handle administrative duties, and creating or expanding cold case task forces to include retired officers, professors, or other hand-selected volunteers. “The real key to overcoming the hurdles is political momentum,” Adcock said. “And that requires pressure from local citizens and community leaders who understand how high the stakes are.”

Dedicating even a relatively small amount of funding to forensic testing can make a huge difference. A cold case DNA grant program from 2005 to 2014 led to the resolution of 2,000 cases, the NIJ report said. Solving just one case can lead to more crimes linked to the same killer.

In 1992, Mike Aamodt, a researcher based at Radford University in Virginia, created the nation’s first public database of serial killers. Students helped gather information on more than 5,600 murderers whose crimes fit the FBI definition: “The unlawful killing of two or more victims by the same offender(s), in separate events.” Many were convicted many years—or decades—after their first known homicide, according to the database, jointly maintained by Radford University and Florida Gulf Coast University. According to the data, just 10 serial killers caught for committing crimes in Texas are responsible for 250 deaths from 1970 to the present.

In 2001, the Texas Legislature recognized the need to address unsolved murders, including serial killings, and authorized the Texas Rangers to create a specialized unit to assist local departments upon request. A DPS spokesperson said via email that the unit has handled dozens of cases, including six serial murder cases in the past decade.

In 2018, Ranger James Holland went to California to meet a 78-year-old prisoner named Samuel Little, a convicted murderer and former competitive boxer. Holland was investigating the murder of Denise Brothers, who was reported missing in Odessa in 1994. Holland brought Little back to Texas and got a prosecutor to waive the death penalty in Brothers’ case. After hours of discussion, Little ultimately confessed to 93 murders and described or sketched his victims. In October 2019, the FBI declared that investigators had uncovered enough corroborating evidence to clear dozens of cases across the U.S. and to verify that Little was the “most prolific serial killer in U.S. history.” In Texas, Little has been charged in Brothers’ murder and also implicated in the death of a woman who was found in a field in 1993 in Lubbock. Police are seeking tips to identify a third woman Little claimed to have killed in Houston.

How many elderly people were marked as natural deaths whose deaths were not natural at all?

But Little’s revelations are unusual. More often when a suspected serial killer is caught, justice system resources are dedicated toward winning a single conviction or obtaining the death penalty. Less effort is devoted to learning how many victims were slain, often leaving homicides unsolved and grieving families with unanswered questions. There are costs to this scattershot approach: In Texas, some bodies linked to serial killers remain unidentified, allegedly interrelated crimes remain uninvestigated, and in some cases, accused serial killers responsible for unsolved murders are released from custody.

Back in 2010, the FBI and a cold case detective began to jointly reexamine the suspicious death of a woman named Ellen Beason, whose remains were found off a highway near Texas City in 1985. Beason’s corpse was discovered minutes from the so-called Killing Fields, a pasture off the I-45 corridor south of Houston where four other women’s bodies were dumped in the 1980s. Investigators believed they were tracking a serial killer.

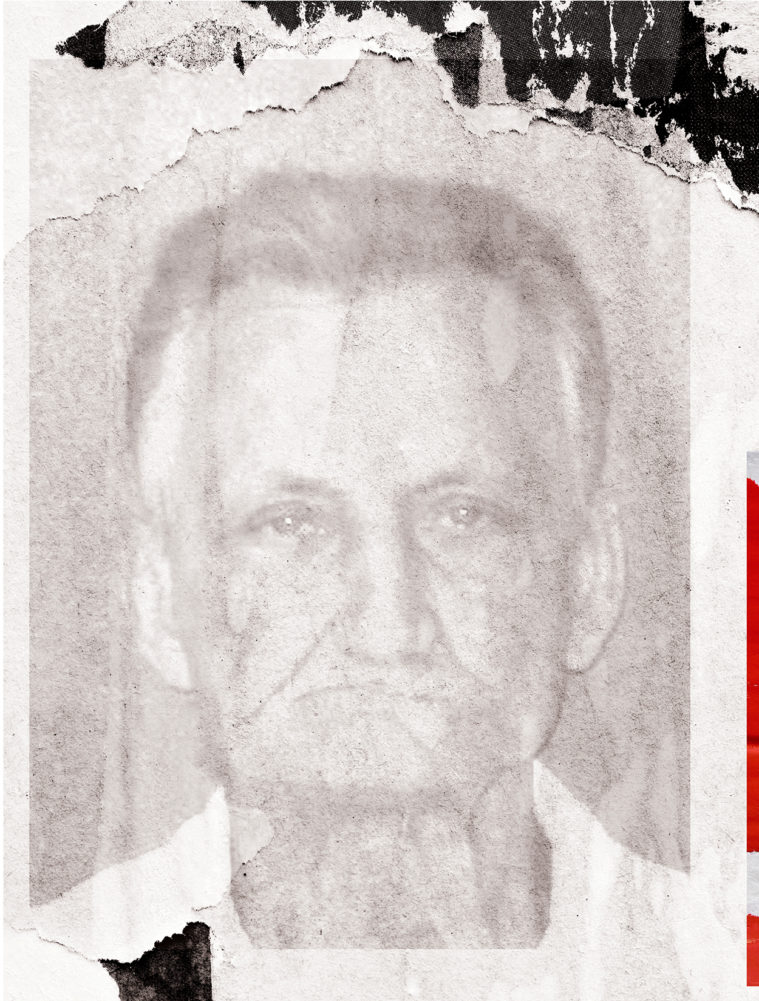

The main suspect in Beason’s murder, Clyde Hedrick, claimed he had met Beason at a bar on July 29, 1984. Beason was his girlfriend’s best friend; Hedrick said he took her to a deserted local swimming hole, had consensual sex with her, and later watched her drown. Afterward, he said, he panicked and stashed the body, which was found a year later when his girlfriend tipped off police. Even in 1985, investigators doubted Hedrick’s story, but Beason’s body had decomposed and her cause of death was undetermined. Ultimately, Hedrick was sentenced to a year for improper disposal of a corpse.

Nearly three decades later, Tommy Hansen, a veteran investigator assigned to cold cases for the Galveston Sheriff’s Department, worked with a local FBI agent to exhume her body for new tests. A 2013 interrogation video captured their subsequent confrontation with Hedrick.

Hedrick, wearing faded jeans and a tight-fitting white sweatshirt, perched in a corner on an office chair as Hansen and the FBI agent questioned him. At first, Hedrick smiled and chuckled, telling investigators he’d once been a “handsome devil” who often met women in bars and won dance contests. Hedrick calmly retold the drowning story, though his smile faded when Hansen handed him a stack of X-rays. Back in the 1980s, the ME’s office had never X-rayed Beason’s body, he explained. The new films showed that around the time of death, her skull had been cracked up one side and down the other from a massive blow.

In March 2014, Hedrick was convicted of involuntary manslaughter and sentenced to prison. At the time of his trial—and later in parole hearings—the DA named Hedrick as the leading suspect in the murder of other women found dead in the Killing Fields, though he was never charged.

The father of one of those four victims, Tim Miller, believes Hedrick killed his daughter, Laura, who was only 16 when she disappeared after walking to a store to use a pay phone in 1984. Hedrick, who lived two doors down from the Millers in the 1980s, had been accused of sexually assaulting other teens. But over the past 40 years, Miller claimed police in League City have lost or misplaced evidence that could otherwise have been tested, including some of his daughter’s bones and a plaid shirt the killer apparently left near the murder scene. Miller recently told one League City detective: “You butchered [the case] 35 years ago.”

Hedrick, now 67, is expected to be released from prison in 2021.

By the time M.J. Jennings finally heard from a Dallas homicide detective in 2018, she had already given away most of her mother’s belongings and cremated her body. Still, the Dallas detective assigned to the case found other clues. He combed through cell phone records and Google location data and discovered Chemirmir had visited Corken’s apartment on the day of her death. Jennings and other relatives were later told that Chemirmir posed either as a maintenance man or health care worker to obtain entry to victims’ homes through force or trickery and smothered those he encountered. Jennings believes that Corken, a creature of habit, was likely followed back to her apartment after getting her hair coiffed at the complex’s on-site salon.

Chemirmir was indicted for Corken’s murder in February 2020, nearly four years after she died. Jennings remains angry that her mother was never made aware of the other deaths and robberies that occurred in the complex. She doesn’t understand why nine similar reports in the supposedly secure retirement community initially seemed to attract so little attention from authorities. She and others allege in pending civil lawsuits that the complex owners should have warned residents, added cameras, and beefed up security.

The corporate owners of Tradition-Prestonwood claim their employees fully cooperated with police. In a statement, the company said, “The Tradition-Prestonwood relied on the investigations of the Dallas police, its detectives, and other reputable, established governmental entities.”

So far, charges have been filed against Chemirmir in connection with eight of the people who died suddenly in that complex. Two other cases remain under review. Soon after Chemirmir’s March 2018 arrest, police said they were reviewing hundreds of cases and feared he could have many more victims, which would make him the nation’s most deadly serial killer. But Chemirmir so far faces 18 murder charges in two counties. In 2019, Dallas County DA John Creuzot said he would seek the death penalty, though the trial has been delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Chemirmir’s criminal defense attorney, Phillip Hayes, has said that his client maintains his innocence; he told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that most of the evidence appears to be “circumstantial.”

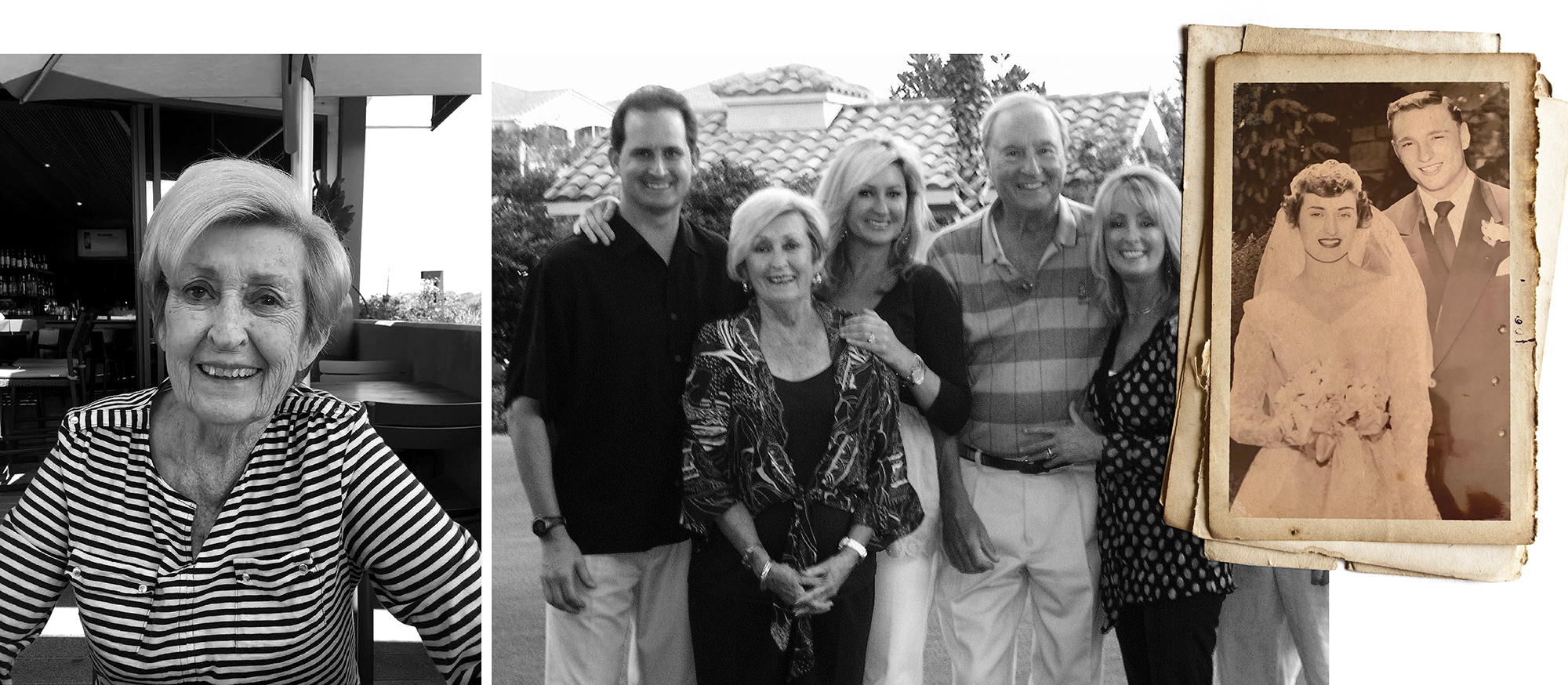

Carolyn MacPhee met Chemirmir in October 2016 when her husband of nearly 60 years, Jack, was dying of a progressive nervous system disorder. The MacPhees had met in the 1950s at Washington State University in Pullman. Even in her early 80s, Carolyn still had the flair of the girl she’d been when they became college sweethearts. She didn’t want to send Jack to an institution, but needed help to care for him in their Plano home. She found Chemirmir, who was working under the alias Benjamin Koitaba, through a service that claimed to vet home health workers, although Chemirmir, using a fake ID and already with a criminal record, should not have passed a background check.

“Koitaba” worked as a replacement caregiver in the MacPhees’ home off and on for four months—long enough to learn the family’s routine and the layout of their home. As part of the care team, he received notice when Jack died. He came back to murder his former patient’s widow six months later, according to a Collin County indictment. When found on Sunday, December 31, 2017, Carolyn was dressed up and ready to go out to church.

Her son, Scott MacPhee, came to his mother’s house to meet Plano police officers that day. He was mystified by what he observed: “It was cold that day, but her coat had disappeared. And two valuable rings she always wore were missing.” He challenged a Plano detective about the missing items, but the response was, according to him, “Old people hide their stuff.” There was blood in the bathroom, in the garage, near her body, and even on her glasses. And yet his mother had no obvious wounds. Officers collected no samples of the blood. Nor did they take photos or videos, he said. No autopsy was ordered by Collin County officials.

The death investigation seemed like a whirlwind, Scott said: “We found her, the cops show up, the paramedics show up, the CSI department shows up, and they rope things off, they do all their investigation, and the detective says she died of natural causes.”

Months later, when he saw the news stories about Chemirmir’s arrest and all the other killings and robberies of older women, he called police again. Eventually, they called back. Through cell phone records, investigators told him they knew that Chemirmir had visited his mother’s home on the day she died. They requested her bloodstained glasses, which he had saved. On them was Chemirmir’s DNA.

So far, Carolyn MacPhee is the only victim whom police have identified among Chemirmir’s former home health clients, although he worked in other homes between 2013 and 2019, her son said. In that same period, police say he was carrying out serial murders.

What Scott can’t stop wondering is this: How many elderly people were marked as natural deaths whose deaths were not natural at all? Publicly, the Plano, Dallas, and Richardson police departments have said that they are reviewing more than 750 other unassisted elderly deaths over the past 10 years, but Scott is skeptical of their commitment to the cold murder cases. “I have no evidence they’ve done that. I’ve seen no more indictments.”

He now suspects his mom, fit and feisty, died only after trying to fight off her killer. He believes other lives could have been saved if the blood the killer left behind in his mother’s home had been tested sooner. “Nothing is going to bring her back, he said. “But if only that detective unit had a little more intellectual curiosity, how many other people’s mothers could have been spared?”