Unpublished Federal Report Projects Bleak Future for Central Texas Mussels and Rivers

Without any conservation measures, four species are “extremely vulnerable” to extinction, according to a draft Fish and Wildlife Service report.

If the state’s population continues to balloon and climate change worsens, four Central Texas mussels could face near-certain extinction, according to an internal analysis by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) obtained by the Observer.

While mussels aren’t exactly the rock stars of the animal world, they play an important role in riverine ecology and water quality: Bivalves siphon off contaminants in water and are widely recognized as a measure of ecological health. To survive, they require a steady and adequate flow of clean water. Put simply, the loss of mussels is a flashing red light for the health of Texas rivers.

The Fish and Wildlife Service has already decided to add one species — the Texas hornshell — to the endangered species list. Now, it’s reviewing whether to also add protections for four other whimsically named mussels (the Texas fatmucket, Texas pimpleback, Texas fawnsfoot and false spike) found only in the Brazos, Guadalupe, Colorado and Trinity rivers.

The 219-page draft report, which has not yet been released to the public and is the first step in the federal agency’s decision-making process on listing endangered species, considers four possible scenarios for the future of the mussels. In the worst-case scenario, with unabated climate change and a booming Texas population, the agency projects that all four species are “extremely vulnerable” to extinction.

“The effects of strong levels of climate change result in even lower stream flows, which lead to increased sedimentation, reduced water quality, and desiccation,” according to the report, which was shared by the agency with a small group of researchers, river authorities and state agencies.

According to the analysis, the four species currently exist in 24 populations. Of them, 15 are “unhealthy” and one population has already been wiped out. Under the worst-case scenario, in 50 years, 19 of the 24 populations will likely be wiped out. On the other hand, if conservation strategies that protect river flows are implemented, the agency projects either maintaining or slightly improving population levels.

The report lists three main threats to the creatures’ survival in Central Texas: degrading water quality, shrinking rivers and an increase in fine sediments, which can smother mussels.

The loss of mussels is a flashing red light for the health of Texas rivers.

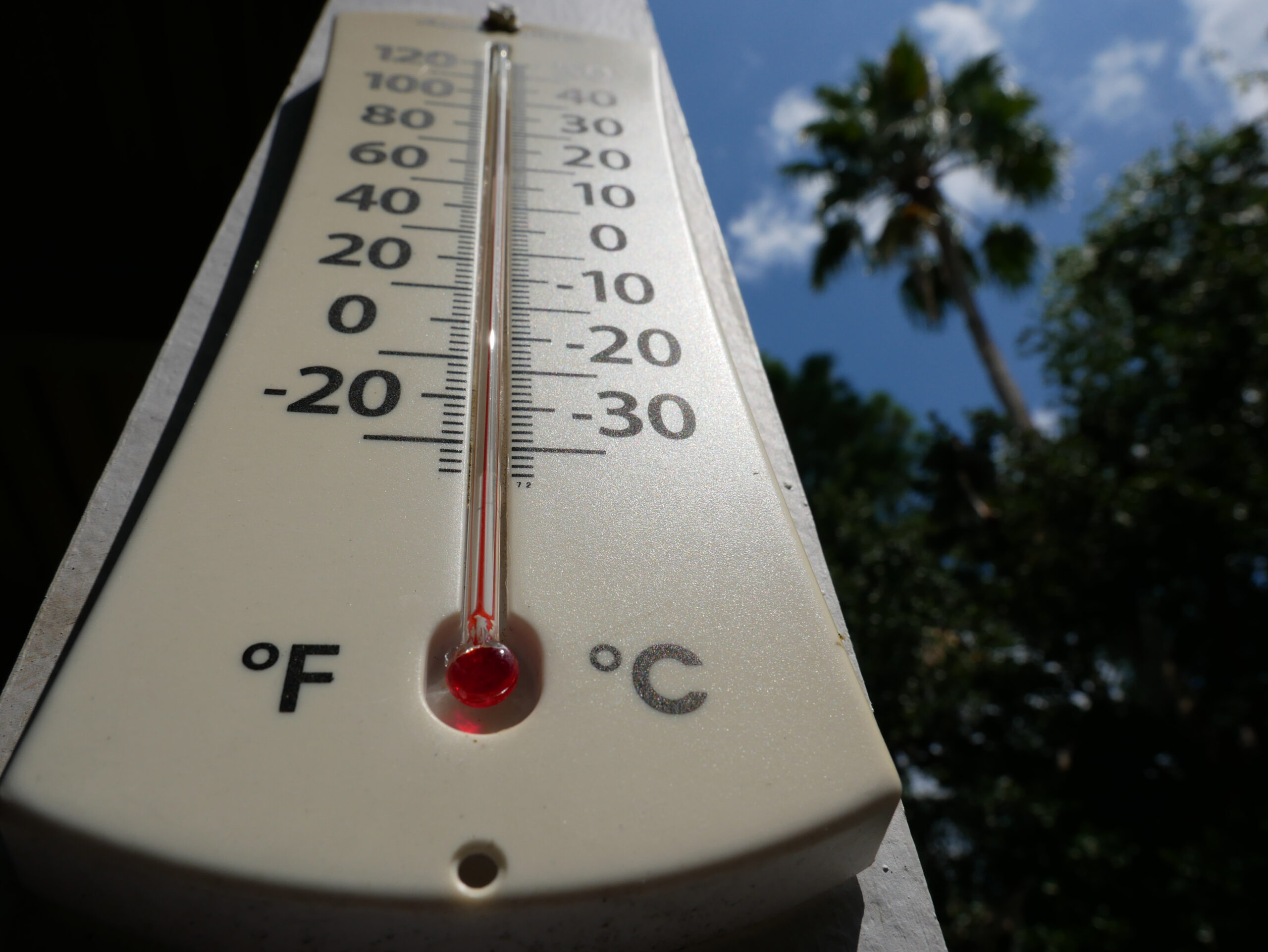

All of these challenges are further complicated by the fact that climate change is bringing longer and more intense droughts, which can increase groundwater pumping and decrease the amount of water flowing in rivers, the Fish and Wildlife Service authors write. Climate change is also projected to lead to a doubling in the number of days with temperatures exceeding 95 degrees Fahrenheit. That, in turn, can decrease water in rivers and elevate water temperatures, placing an additional burden on the river-dwelling critters, according to the agency.

Lesli Gray, a spokesperson for Fish and Wildlife, cautioned that the draft report was subject to change in the coming months. “It’s a work in progress,” she said. The agency is soliciting feedback about its analysis from industry groups and researchers and expects to make a decision about listing the four Central Texas species by the end of the year.

The new assessment doesn’t bode well for industries, politicians and river authorities hoping to avoid regulations that come with an endangered listing. If the mussels are considered endangered, FWS could set limits on how much water can be drawn from the rivers, portending immense consequences for the numerous oil and gas operators, farmers and cities that depend on the rivers for water.

The threat of red tape has resulted in political handwringing around a handful of mussel species in Texas. For example, Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar last year awarded a $2.2 million contract to researchers to study the Central Texas mussels. Some researchers criticized the effort as a way to rig the process and produce science that supported not listing the species as endangered.

Raymond Buck, general manager for the Upper Guadalupe River Authority, said that he’s “still evaluating the entire listing process and rationale for doing so.” The Texas fatmucket and Texas fawnsfoot are found in the river authority’s jurisdiction. Buck said that they have “a number of programs” to protect the habitat along the river.

“Though we side with conservation, we are not in favor of onerous federal regulations. We believe the best stewards of the Texas Hill Country resources are private landowners and local entries,” he said.