‘Nobody Has Accepted Accountability’: Uvalde Families Demand Change to Police and School Personnel

After the release of a damning House report, a Monday night school board meeting became tense and passionate as organized Uvaldeans refused to be silent.

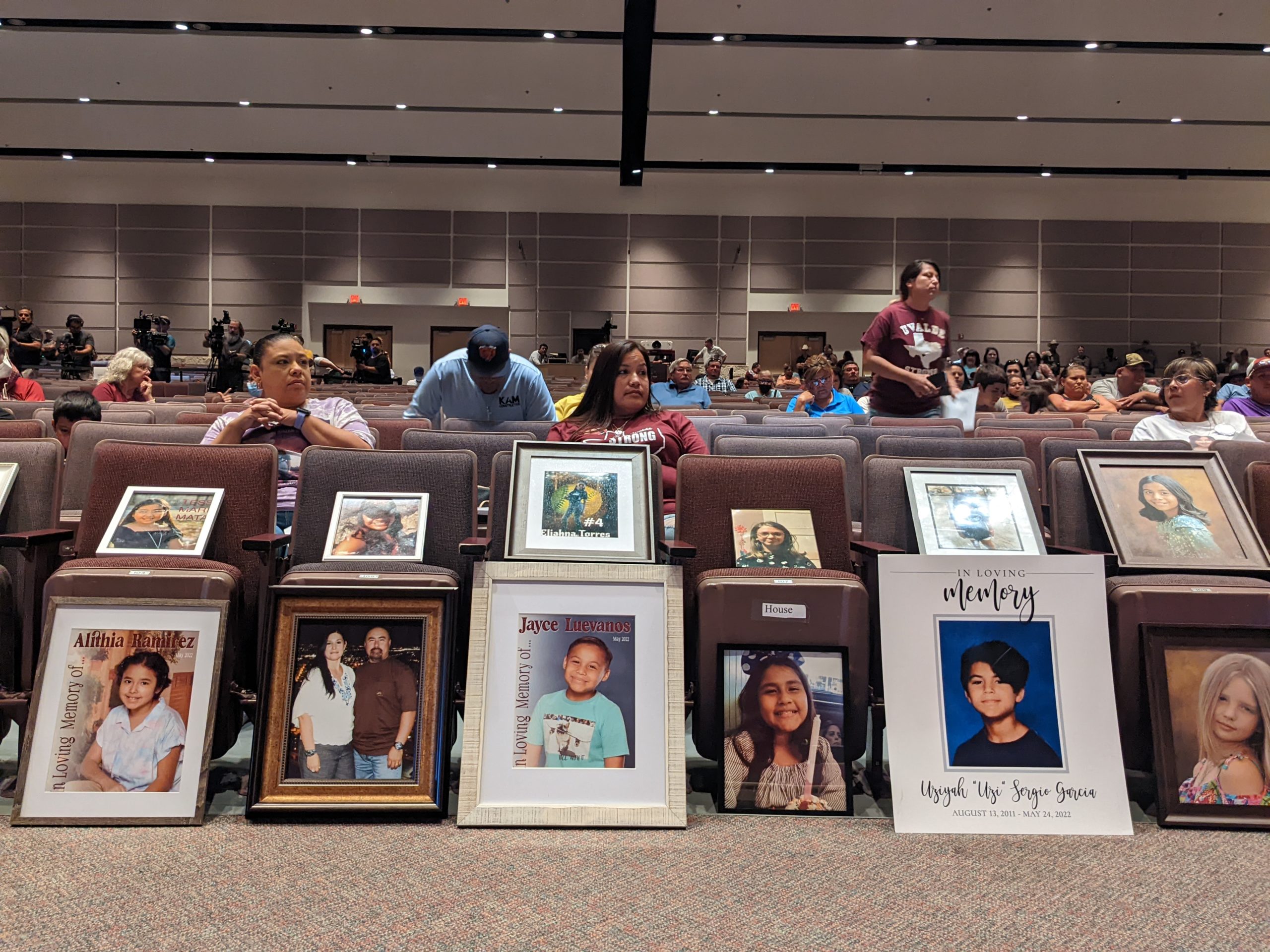

On Monday evening, almost two months after the deadliest school shooting in state history took place two miles across town, a crowd of Uvaldeans trickled into their South Texas city’s spacious high school auditorium for a special school board meeting to weigh in on the now-frightening prospect of the incoming 2022-2023 school year. In the front row of seats, families placed photographs of the victims—19 elementary schoolers and two teachers—slain on May 24 by an 18-year-old man with an AR-style rifle.

After a brief introduction from Superintendent Hal Harrell—in which he said the district would improve school perimeter fencing, door-locking mechanisms, and review emergency communications systems—incensed community members quickly seized control of the meeting.

“I just want y’all to take a look [at the photos]; those are our babies, those are our teachers, and they’re no longer here, and what y’all have been lacking to do is be accountable for y’all’s mess-ups. … Nobody has accepted accountability so we’re going to force y’all to,” said Brett Cross, uncle and guardian of 10-year-old shooting victim Uziyah Garcia, drawing shouts of support and applause from the crowd.

As many speakers would, Cross demanded that school district Police Chief Pete Arredondo—currently on administrative leave—be permanently terminated for his bungled response to the shooting scene. “If he’s not fired by noon tomorrow then I want your resignation and every one of your resignations because y’all do not give a damn about us,” he said.

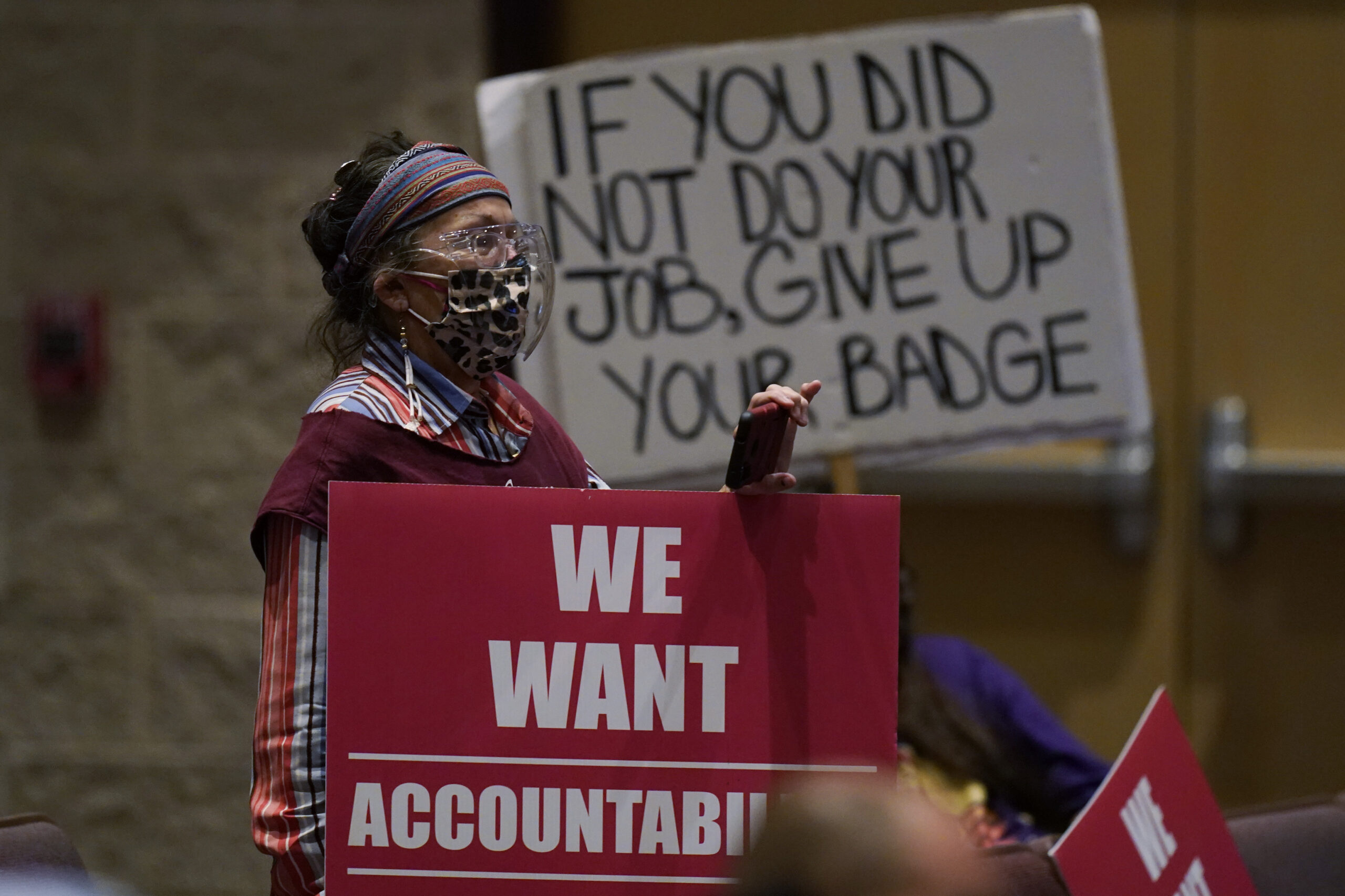

One man stood off to the side of the room holding a pair of bright red signs reading “Prosecute Pete Arredondo” and “We Want Accountability.” As speakers grilled the board, the crowd regularly yelled “accountability,” “answer the question,” and sometimes “cowards.” Some demanded the superintendent be fired.

A number of parents said they did not feel comfortable sending their kids back to Uvalde CISD next year; one threatened a “walkout.”

“How am I supposed to come back here?” asked Jazmin Cazares, a Uvalde high school student who lost her nine-year-old sister Jackie in the shooting. “I’m going to be a senior; how am I supposed to come back here? What are you going to do to make sure I don’t have to watch my classmates die, to prevent me from having to wait 77 minutes bleeding out just like my sister did?”

Superintendent Harrell said they were still reviewing information—including a recently released Texas state House report—to make a final decision on Arredondo’s employment. He also said the board planned to delay the opening of the next school year past Labor Day to improve security.

The school board meeting took place a day after the House committee tasked with investigating the Robb shooting released its preliminary report on the tragedy. The bipartisan committee drew on dozens of closed-door interviews to conclude that the disaster resulted from “systemic failures.” The report spread blame widely, from a “regrettable culture” among school staff of propping open doors to the broader school system, for letting the 18-year-old killer fall through the cracks. It also criticized both law enforcement and media for spreading incorrect information after the shooting.

In passing, the document—which doesn’t include policy recommendations—mentioned that “there was no legal impediment to the attacker buying two AR-15-style rifles, 60 magazines, and over 2,000 rounds of ammunition when he turned 18.”

The report revealed that a stunning 376 law enforcement officials from 23 separate agencies converged on Robb Elementary School that day to then, collectively, fail to take out the killer for some 73 minutes. Of these officers, 240 belonged to the federal Border Patrol or the state Department of Public Safety (DPS), a function of Uvalde’s inclusion in Texas’ militarized border region. Rather than heaping all blame on school district chief Arredondo—as state police Director Steve McCraw has done—the House committee report spread the blame around, describing “an overall lackadaisical approach by law enforcement at the scene” while noting that various officers could have taken command of the chaotic situation at various times.

Last week, the Austin American-Statesman and KVUE published a leaked video of the police inaction.

Following the report’s release, the city placed Lieutenant Mariano Pargas, who was acting police chief on the scene, on administrative leave. The House report does not conclude whether lives were definitely lost due to delay, but it does state: “Given the information known about victims who survived through the time of the breach and who later died on the way to the hospital, it is plausible that some victims could have survived if they had not had to wait 73 additional minutes for rescue.”

A little more than two hours into Monday evening’s testimony, Vicente Salazar, grandfather of 10-year-old Layla Salazar who was taken by the shooter, took to the podium.

“We pay over 40 percent of the city budget for the police and you hired trash, that’s not right,” Salazar thundered. “I lost a loved one right here, my only granddaughter. I can hold myself together now because I’ve done my crying, now it’s time to do my fighting. You’ve seen me in the papers, and you will see me in the papers a lot more, because this isn’t the end, this is the beginning.”