‘Don’t Suck, Don’t Die,’ Kristin Hersh’s Raw, Post-Mortem Plea

Vic Chesnutt, who wrote and performed songs with unwavering honesty about darkness, pain, and the small, sweet bits of life, died on December 25, 2009 after overdosing on muscle relaxants. In an interview weeks before his death, he told NPR that his song “Flirted with You All My Life” was actually “a breakup song with death. … You know, I’ve attempted suicide three or four times. It didn’t take.” Paralyzed since his 1983 car accident, he told NPR he was $50,000 in debt and had put off surgery for a year because he was uninsurable.

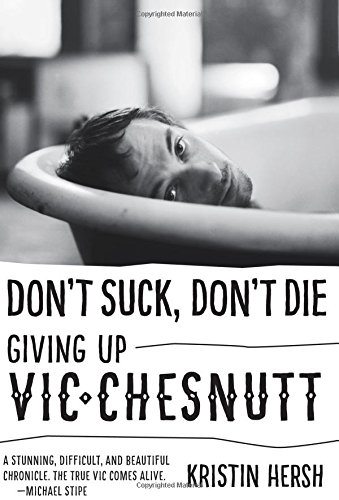

Playing with two fingers, Chesnutt created an idiosyncratic, authentic body of work admired, even revered by fellow musicians. Michael Stipe produced two of Chesnutt’s albums. Now, he is memorialized by his musical partner and friend, Kristin Hersh, in her memoir Don’t Suck, Don’t Die (University of Texas Press, October 2015). Written in second person, the book is an extended conversation with Chesnutt drawn from funny, quirky exchanges during the years when he and Hersh toured together with their spouses. The book is a love letter between friends and a raw, post-mortem plea, all the more wrenching for its futility. Hersh writes:“We all tried to keep you talking, because shutting up is shutting down, and we were already a little lonely knowing how close you were to checking out.” The first chapter of Don’t Suck, Don’t Die, which follows Hersh’s acclaimed Rat Girl, is excerpted below.—Nancy Nusser

*****

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Vic Chesnutt wasn’t destined to enjoy the success many of his fans enjoyed. He influenced many and died too soon … an old story, but in this case the story of one of the best songwriters of our generation. He and I toured together on and off for about a decade or so and I’d say we were close, though nobody was ever close enough to Vic to cart him out of his valleys and push him up into the peaks where we all wished he’d just set up camp and send more songs rolling down that mountain into our waiting ears.

The car accident that left him a quadriplegic at age eighteen was probably his most gaping, obvious wound, but there were others. Vic was not gonna stick around, in other words, unless you believed his stories of Old Man Vic, parked on his porch in Athens, Georgia, with a shotgun aimed at all comers. I definitely believed that story, because I wanted to, and because when he was alive, he was so alive. I mean, every day . . . until he wasn’t anymore.

K.H., Rhode Island, May 2015

Eat Candy

Stepped out of the icy Alabama truck stop and into the searing sun, crinkling a bag of cinnamon Jolly Ranchers in my left hand and holding the door for a big ol’ son of the south with my right. No way northern winters are as cold as southern air-conditioning.

Through the windshield, you did that squinty thing you used to do, when nobody could see your eyes, but somehow they were still shattering blue portals, letting everything in and nothing out. Nothing but a pinpoint of black hole judgment. The judgment was cold and cruel and… well, unnecessary, if you ask me. The blue portal thing was sort of blank, but the judgment always came through loud and clear. It made people cringe; so weird and unsettling. But I was used to it, so I just squinted back. No judgment in my squint. I squinted like a dog in the sun.

The son of the south dude balanced a box of hot dog and potato chips on a flat palm and stared into the parking lot wistfully. Sighed with his whole Buddha belly, squeezed lightly between suspenders, suspended over failing dungarees. His whole being was about suspension, actually. Fairly typical of a trucker. He was just . . . waiting. And his little pointy sneakered goat feet barely touched the ground. Big, fat hover dude.

Your driving glove on the steering wheel at three o’clock, you tried a muted version of the squint at me, but it wasn’t gonna work. And anyway, your heart wasn’t in it, cuz you hadn’t had your awful cawfee yet. I smashed the Jolly Rancher bag up against the glass and smiled with all my evil teeth. “Eat candy!”

You, dull-eyed, through the glass: “What?”

I made the roll-down-the-car-window motion that hasn’t made sense since the eighties and you said something I couldn’t hear.

Me, dull-eyed, through the glass: “What?”

Shaking your head, you pointed at the AC. I rolled my eyes and let the Jolly Ranchers fall to my side. “Pussy. It’s just sunshine.”

So you leaned to your left and your elbow hummed the window down about three inches. Cuz nobody could call you a pussy and get away with it. Or else somebody who called you a pussy could get away with anything, I dunno. “You! Are the sunshine pussy and you know it!” you crowed. “Ain’t nobody scareder of sunshine than you, Hersh.” Then you got lost in syllables for a minute: “Sacreder, scareder… scared o’ sacred sun …”

Me: “Stop that.” My deformed lips shoved themselves into the three inches of van interior you’d allowed them.

“Sunshine is poison. But listen. Sweetness isn’t something you can control. I mean, like hardly ever. You understand? It doesn’t just come to you.”

Stare. We’d been engaged in this candy debate for months. The whole tour, in fact. That sentence alone, I had uttered at least six times. Also this one: “Whatever gets you through the night, but you gotta do all of it, just in case you haven’t found the right one yet. Cuz then dawn comes and it’s too late.”

“You said the dawn thing before.”

“How many times? And you still don’t listen.” I held up the garish, fluorescent-orange bag to illustrate my point. Sparks of Alabama sun bounced off it onto my reflection in the window. “This here? Is a bag of control. Grab sugar wherever it falls.”

“What?” Shaking your greasy head. “That is prob’ly the gayest thing you ever said.”

Ignore. “Straight vodka? Only dulls, it doesn’t bring anything to the table. And black instant coffee, for christ sake. It’s cruel.” Stare. A little duller than before even. “I think you invented black, instant coffee. Nobody on earth’d drink it except you. And you drink it lukewarm. God.”

You leaned your elbow to the left again and the window closed about an inch.

Me, grim: “Nothing nice is necessarily gonna kick in is all I’m saying.” I tore open the bag of Jolly Ranchers and jammed a fistful through the narrow opening in your window. You watched the candies fall into your lap. “A little tonic water, some cream and sugar; sometimes they’re your only friends.” Stare. “And eat candy, dammit.”

That was all I had, really, and it wasn’t exactly changing your life the way I’d thought it would. I figured all the talk of the last few weeks just needed some warming up with a visual aid. But you were staring at little red spheres of corn syrup and red dye number forty, serotonin levels hadn’t spiked, and childhood memories of Halloween and Easter hadn’t been triggered. No sugary spin had softened the noisy highway behind us or the smell of hogs and gasoline in the air. The son o’ the south was still planted and wistful, suspended.

For me, cinnamon Jolly Ranchers brought forth a sensory- almost-overload of a particularly intense memory lane: terror and new love, shattering agony and heights of passion. It didn’t say, “TERROR, NEW LOVE, SHATTERING AGONY AND HEIGHTS OF PASSION” on the bag, though; it just said, “CINNAMON” and it maybe had some flames on it. But you weren’t even getting that, cuz you wouldn’t goddamn eat the things.

Picking up your head, you stared through the windshield. That son o’ the south was like, frozen. Frozen on the sidewalk in front of the van. It was weird. Lost his truck, I guess.

“Thank you,” you muttered into the windshield.

When Tina appeared on that searing sidewalk—all rosy softness and dark kindness, half a dozen braids brushing her shoulders, your sad instant coffee in her hand—the son of the south moved out of her way delicately. Floated a few feet to the left with his box of hot dog. His hot stare settled on you and your blank, hot windshield face, his hot hot dog glistening.

Me: “Your wife’s here. Be nice or she won’t give you that cup of awful.”

You weren’t always nice to that quiet woman. I could never really forgive you the kindnesses you sometimes let fall on Tina’s gentle shoulders. Maybe because I didn’t understand, and maybe you weren’t asking to be forgiven. Could have been between y’all and none of my business. In fact, I know that’s true, but still . . . I was trying to keep you alive. Sugar is one way to enjoy being here, gratitude another.

Since Tina only had about half a dozen braids, though, glinting in the truck stop sun, I knew it was an okay day. She braided her hair when she was stressed out, and I’d seen her get up to about thirty little tiny stress braids. Two on a good day, her dark brown curls loose on the best days. Six was okay, though. The braid barometer was a fairly accurate one, so maybe you’d been a sweetheart this morning. That’d be nice. One step closer to heaven for Bitch Chesnutt.

You: “Go home to your husband and leave me alone.” You watched the hot dog trucker with interest.

I turned to look at Billy, parked in the next spot, studying a map. He glanced up, smiled and waved, then returned to his map. “I think I will,” I told you. “And I’m taking my candy with me.” I tossed a fistful of Jolly Ranchers through our car window and Billy grabbed one off the seat, businesslike, cuz he knew the value of a woman holding sweetness in her hand. He’d taken part in the sweetness debate only in gentlemanly fashion: presenting y’all with beautiful vodka tonics and lattes, etc. He didn’t smash candy onto your window. I believed in the direct approach. “Childlike,” Tina called it. “Dog-like,” you’d responded.

Now you and Tina both stared thoughtfully at the hover trucker, who was then joined by another trucker, holding a bag of Slim Jims and a vat o’ soda. Together, they shuffled sadly away, into the bright white parking lot.

“Why won’t faggots just be gay?” you asked with genuine concern.

___________________

By Kristin Hersh

UT PRESS

198 PAGES; $22.95 UT Press

The first time I saw you, you were standing on stage, bent over an amp and fiddling with the knobs in back, in soundcheck mode: a little uncertain, a lot frustrated. Every stage is a new terrain you gotta feel out and not all ropes can be learned, of course. Some of them balk at the suggestion, sneakily knot- ting themselves into your very own customized noose. We hang ourselves regularly when we’re supposed to be making church happen, supposed to be floating song bodies out over the audience, supposed to morph into thick clouds of sound and back again.

And we’re s’posed to time-trip. Time-trip from size 6X: young and fragile and confused, trying to work the spaceships we just got born into, to ninety: old and fragile and confused, trying to MacGyver our busted old spaceships into working parts that can, say, order a pizza over a fuzzy cell phone. Which we can’t.

We’re supposed to be slipping syringes of memories and their analogous chemicals into our bloodstreams and spitting out their shaky stories, supposed to be saving our own asses and the listeners’ with our broken balls. You, when I said that: “Blah, blah, fucking blah.” Because instead, we usually just highlighted the dumbass in all of us. “Retard Christ,” as you so eloquently put it. Crucified on our freakin’ mic stands.

“Well, that counts . . .” I tried.

You shook your head. “Just the difference between special and special.”

Not having met you yet, though, I didn’t know you were snide or magic. I watched you lean from side to side over your amp the way I do mine when it doesn’t offer enough toggles, switches, and knobs to make a guitar sound good enough to give us a reason to ever have been born. Where are all the other switches? The better ones? Your forehead pressed itself into the silvery gray canvas, your knees buckling. I knew that posture in my own body so well, I figured we’d either get along great or hate each other.

Neither, as it turned out. You ignored me until somebody told you my last name, and then you pretended to pray to me. Both were weird; I kept my distance.

Anyway, I never saw you stand again.

The first time I saw you play, I watched snowy white wings unfold behind your wheelchair, poking out of your lumber-jack plaid, as a six-year-old boy morphed into ninety-year-old man and back again. The spaceship dealie. The sound this made was . . . I’m gonna say “perfect” because you aren’t around to hear me say it. Also because you played bass, lead, and rhythm in the same song, with only two fingers. Never heard anybody else do that before or since.

And poetry. I’m not even someone who uses the word poetry, but I’m gonna say your poetry “cascaded” because you would’ve loved to hear me say that. God, I cringe just typing it. But honestly, it was remarkable. The tumbling of it all.

Your rumpled self in rumpled clothes playing rumpled-up songs like you’d just grabbed them out of a corner of your bedroom and stuffed ’em into your suitcase before you left on tour. Which, I know, is basically what you did. Because Billy and I could hear your house in them, even though we hadn’t been there yet. We could hear your hated and beloved books: paperbacks your junkie lumberjack friends’d make you read just to hear you whine about pretense and unfounded security. And the old, old, falling-apart hardcovers you’d rattle on about: their grasp of indecency and fortitude, our universal weakness and susceptibility to love lost and weather and societal convention. Which, miraculously, still had you by the throat somehow. Old when we were young, you remained out of time the whole time you were here.

We could hear your loose, rattling effects pedals that’d run out of batteries, which you considered a hopeless situation and so had tossed them into the corner to live with the spiders. We could hear Tina’s mason jars of lentils and buckwheat, could hear the rain on the metal roof of your porch. We could hear your banging pipes, which you also considered a hopeless situation. So did Billy and I, shaking our heads in frustration. Because if anybody called the plumber on you, you guys’d just hide when he came to the door. Even if it was you who called the plumber, you’d hide. We didn’t know this yet, of course, but I swear, we could hear it. And that wasn’t us, it was you. We weren’t psychic, you were just a wicked salesman.

When you opened your battered old suitcase onstage and snatched another wrinkled, wadded-up song out of it, Billy and I could hear the tacky flowered sheets we would sleep under a hundred times in the future, could hear the okra growing in your backyard. We felt your kitchen pressing in: the room the four of us’d laugh so hard in, make each other wince, catch our breath, then laugh again. We were gonna make each other better, smarter, happier people in that kitchen. I already felt less lonely.

Cuz I could see the knick-knacks you would collect on our tours—also in the future—and the glass case you’d use to display them. Never quite the collection I expected it to be, given where we’d all go together (everywhere) and what confused us (everything). Never the treasures that would’ve reflected any kind of “universal weakness” or your mixed-up commie-libertarian leanings. You probly should’ve put Tina in charge of your treasure hunt. Still . . . the Six Million Dollar Man is pretty cool, I guess. Especially if you find him in Barcelona.

When you played, I heard the menagerie next door, the thirty-odd birds that dusty, hairsprayed woman kept inside with her and all the windows shut. Rats upon rats in her attic, Billy behind me on her stepladder, Tina behind him, my face sticking up through the hole in that wacky woman’s ceiling, level with the rats. “Back up,” I would hiss to our mates in the future. “Go back down the ladder.” Wolves in her backyard.

I heard southern trees dropping their leaves on your poor exposed porch. And I heard us walking to the co-op in the dark, your wheels splashing quietly through shining puddles on the sidewalk. Billy and Tina’d be murmuring up front, talking sweet sense, while you and I tried to arrange our precipices of flights of fancy of flying off cliffs into healthy thought forms that didn’t sound as obnoxious as the way I’m describing them now. We were unsuccessful, obviously, but it was funny and that counts. Then we figured out all we had to do was present Billy and Tina with the puzzle pieces and suddenly a clear picture would emerge from our messy pile; our patient, bemused spouses smiling gently.

We also never learned to get pizza out of a cell phone, always fucked that up. Didn’t even seem that hard, but confusion was in our sphere and out of our control, as if we caused it in others who’d then confuse us. The pizza people’d call you “ma’am” and me “sir” and it’d shake us up enough that we’d just pass the phone to Tina, who’d pass it to Billy.

But laughing is maybe better than clarity, I dunno. Pretty in the moment. What I wouldn’t give to live in one of those moments. The pretty, laughing ones.

When Billy and I finally saw your house, it was as if we’d been there a hundred times before, having heard you play at least that many times. And then it all kicked in, came true, living backwards like songs make you do after allowing you a glimpse of the future, whether or not you wanted to see it. They tell you the whole future, see, and I wasn’t cool with it. Who would be? It wasn’t cool.

But laughing is maybe better than clarity, I dunno. Pretty in the moment. What I wouldn’t give to live in one of those moments. The pretty, laughing ones.

Grandma Vic. It was like you were sitting there knitting and chatting and patting the rocker next to you, inviting us all to have a seat. And, vague, uninterested, unsold, we’d look at our watches and glance over your shoulder for something better to do, something a little more exciting. It just seemed so fragile, what you did. Or quiet, or something else that might bore a rerun-addled attention span. Then you’d pat that empty chair again and wheedle-whine that you had a story to tell.

I got five minutes, we’d think and give you about that much time. But just as we were getting settled and feeling bigger than your quietness, some snow white wings’d appear behind your wheelchair. Spreading out ominously, they’d frame your odd posture, drawing our eyes away from those bony chicken wings of yours that were coming too fast for us to see. Then Grandma Vic, hell’s pretty ugly angel’d jab us with a knitting needle, straight through our meat. Sometimes you’d aim for our hearts, sometimes for our viscera, sometimes right between the eyes, but every hit was a goddamn bull’s-eye and us not even seeing it coming.

Never underestimate Bitch Chesnutt. That left of yours, my god: up and out. We didn’t stand a chance because when you were good, the work was true. And by that I mean you were goddamn flying around the room, over our heads, kicking the crap out of us mole people. Stunned and wounded, we saw you suddenly as yourself: glistening, a murderous look on your face. That look that said, “this is what I do.”

And then you achieved every songwriter’s goal, cuz you made us think: I’m not alone.