De Stijl Displays the Identity-Conscious Work of UT-Austin’s Only Black MFAs

One/Sixth, the art display on exhibit at the new De Stijl Gallery in Austin, evokes the fraction of Texas (and the country, more or less) who can claim African heritage. It also refers to the paltry number of black artists who have passed through the University of Texas at Austin’s visual arts MFA program since its founding in 1961. De Stijl’s curators identified only six black MFA graduates, and, since the announcement of the exhibition, a seventh has surfaced.

“This seemingly insignificant numeric,” writes Northwestern University Ph.D. candidate Jared Richardson in his introduction to the exhibit’s beautiful catalogue, “gestures toward a noteworthy, fractional state of diversity and inclusion.” The graduation of these six, now seven artists offers scant evidence of a post-millennial upswing in inclusiveness: Two artists on display graduated in the 1980s, two in the 1990s and just three in the first decades of this millennium.

Portrait artists Robert Pruitt and Zoë Charlton provide the most immediately accessible work on display. Pruitt’s “Stone Cut” (2011) features a man with an afro hairstyle that has grown into a sort of pyramidal temple; a similar work, “Tipping Point” (2013), shows a cosmopolitan black man, with stubble, glasses, and polo shirt, balancing what looks like a thatched-roof hut on his head. “Pruitt’s portraits humorously illustrate the temporal paradoxes blackness often bears within the Western imaginary,” Richardson writes. Pruitt’s pictures sit at the meeting point of the two terms in the “African-American” label, conjuring fantasies of identification that might occur either to American blacks seeking a connection to a distant heritage or to American whites compelled to see exotic otherness in any dark-skin hue. Pruitt was named Artist of the Year at the 2013 Houston Art Fair.

One/Sixth is important for exhibiting this flowering just a few blocks from the campus where its artists made professional strides against the grain of a homogenous arts academia.

“[N]ot all of the artists featured in One/Sixth explicitly address race and/or blackness,” Richardson writes, reminding viewers of the “dilemma of over-determined reading of race in work by black artists.” Janaye Brown, the most recent UT MFA graduate on display, works in video, and Richardson identifies her subject as boredom — “the slow contemplation of the quotidian.” Certainly her short films lack the dramatic tension of typical Hollywood entertainment, but I’m not sure she’s transfixed by boredom. I’d guess her subject is something more like respiration — for instance, the push-pull of desire, as in “Last Night,” a video taken in the back seat of a car during a long, silent ride with a mystery woman. In “Rocks with Salt,” Brown’s camera observes an undulating mound of sand, perhaps breathing along with the ocean, maybe containing a buried person. Brown’s aims could be intentionally mysterious.

The same could be said about Houston-born Steven Jones, who contributed two very different works to One/Sixth — an orb-shaped sculpture covered with a mosaic of jagged black tiles and halved die, called “26 Degrees” (2016), and a map of northwestern Pennsylvania covered in a Rorschach-y inkblot, called “Lake Erie” (2014). Like Brown, Jones seems to be working with images and shapes from his subconscious, deep, mute, and untranslatable.

The final two artists on display, Walt Kisner, faculty emeritus of St. John’s School in Houston, and Christina Coleman, who lives in Austin and contributed as a curator to the De Stijl show, are especially intriguing, given their art’s more slippery relationship with identity themes. Coleman’s sculpture “Black Blonde” (2015) is the most eye-catching, non-pictorial work on display. It looks almost like a piece of electronic equipment, a large antenna or capacitor, wound with brightly-colored wire. In fact, the wire is synthetic braiding hair. “This highly politicized fiber is intertwined with complicated histories of respectability, cultural appropriation, and myths of racial and ethnic identity,” Richardson writes.

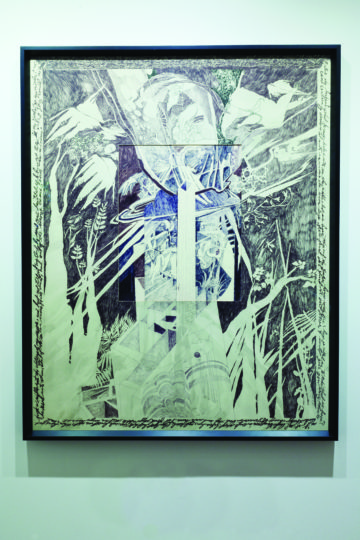

Kisner’s wall hangings, like “Solomon’s Garden, Deeper Than Love” (2015), are sublime, prismatic religious visions. “Solomon’s Garden,” according to Richardson, uses an encaustic technique from the Byzantine era. It creates the aura of a stained-glass window, the texture of parchment, and it resists easy reading. Gazing into the work is like peeking through wind-ruffled foliage by the light of a reddish moon. We’re not sure if we see stalks or figures cavorting, bobbing flowers or raised fists. Richardson, describing the work’s “vegetal forms that toggle between figurative and abstract,” sees in Kisner’s biblical subject matter “an ancient allegory for freedom.”

The six diverse approaches to art and identity are variously beautiful, moving, and thought-provoking, and One/Sixth is important for exhibiting this flowering just a few blocks from the campus where its artists made professional strides against the grain of a homogenous arts academia. Upon entering the exhibit, though, a different kind of diversity takes precedence: the rich variety of styles for engaging heritage, history, and pure aesthetics in an era of stunted integration.